Welcome to the fifteenth Poltern Newsletter 📨

This month’s issue includes a piece on assemblage and symbolism prompted by the haunting work of Arturo Kameya, written by Darcy Lannen Olmstead; a hybrid exhibition/book review on the joint power of visual and textual histories represented in Hilton Als’s exhibition, Toni Morrison’s Black Book, by Victoria Horrocks; a reflection on opacity as seen in recent Yale MFA Emma Safir’s sculptural digital collages by Carlota Ortiz Monasterio.

If you have any questions or comments, please reach out to us by responding to this email or writing us at polternmag@gmail.com.

Thank you for being here.

The Poltern Team

A quest for opacity: Emma Safir’s sculptural digital collages

by Carlota Ortiz Monasterio

Upon entering Emma Safir’s solo exhibition with Baxter Street at the Camera Club New York, one is surrounded by the looming presences of eight densely composed panels inhabiting the intimate gallery space. Hung on the walls or reclined against them, the photographic collages, printed onto fabric, stand out for their ambiguity: they simultaneously fall within the mediums of photography, painting, textile work, digital collage, and sculpture. A recent Yale graduate from the MFA in Painting and Printmaking (2021) known for her multi-media practice, Safir explores the tension between transparency and opacity in images and their role in influencing how we inhabit both physical and virtual spaces. Created through various digital and manual manipulations, the pieces in the exhibition—all made in the last two years—reveal the artist’s quest to unveil images’ inherent opacity.

Her process starts with selecting images from a vast personal archive of spontaneous photographs, which include views of domestic interiors, nature, landscapes, textile patterns, and windows. The images are then scanned and superimposed into digital collages printed on fabric. The compositions are further abstracted through the addition of veils, patches, and pockets in tulle, spandex, and appliqués created through the traditional textile techniques of weaving, smocking, and upholstery. Finally, they are attached to a layer of foam and a wooden base acquiring a convex sculptural appearance. Rooted in a consistent layering, veiling, and glitching of images, Safir’s practice challenges the straightforward reading of images.

A vital aspect of the works at Baxter Street is their muted palette. In obscure tones of purple, pink, brown, blue, and gray, Safir’s compositions seem to not only favor but strive for dimness and opacity. For example, Veil III (2020) superimposes a white grid over a dark pattern of brown and blue streaks and indistinguishable faint white shapes. An unaltered photograph of a highway road, seen from a bus’s dark interior, emerges from the bottom right corner, interrupted by a rectangular painted multicolor chromatic grid. At the same time, two white rectangles hang nearby—finally, two intricate veils composed of pink and black tulle fall over half of the composition. The frequent reference to optical devices—windows, fences, and veils—highlights the tension between what images reveal and what they may hide, a concept that animates the artist’s practice.

One of the largest and most intricate compositions, Rewound Glitch II (2022), bulges out of a white wall. From a distance, the base surface looks like an intricate brocade of floral patterns. Yet, as one gets closer, the illusion of texture is broken by a staunch flatness. The dense interweaving of color “threads” into rich patterns results from a deft digital manipulation through rasterization, a computer graphics process that converts images into more reduced sets of pixels or dots. Creating these confusions between digital and manual work is at the core of Safir’s brilliance. Small protruding pockets cover the surface like raindrops trickling down a car window to add to its complexity. At the same time, two intricately worked pieces of fabric—using a smocking technique that allows for the material to hold its form—are attached to the bottom corner. The manual weaving process of these added layers and the process of digital manipulation employed to create the backdrop image mirror each other and problematize the perceived differences between these forms of labor.

Indeed, a critical investigation into feminine and digital labor is the conceptual backdrop to much of Safir’s practice. In a recent workshop with designer Luzia Dale, Safir gave an insightful lecture on the connection between textile labor and the development of computational systems, emphasizing the essential role women have played throughout. She traces this history from the early forms of computing, like the abacus and the Andean khipus, to the Jacquard punch cards and the Analytical Engine developed by Ada Lovelace in the 19th century, to the semiconductors developed for space travel using the skilled labor of Navajo weavers and women, to the MIT core rope memory chips also known as “little old lady” for the women that created them, through to the numerous female “human computers” at NASA and the so-called “computer girls” IBM programmers in the 1960s. In doing so, Safir illuminates the profound entanglement of gender in technological development. With this historical perspective, her work critically questions the demotion of feminized and manual labor in the present capitalist and digital era. In their recurring use of veils, patches, and pockets, Safir’s works make visible, in fastidious embroidery, a form of labor that has historically been dismissed, undervalued, and made invisible.

Safir’s research in the relation between gender and technology is also concerned with new forms of unpaid technological labor. In particular, the control logic behind services, such as Google’s reCaptcha (the ubiquitous visual puzzles), are marketed to protect websites from bots yet crucially help train the platform’s artificial intelligence. The interest in these new forms of invisible labor elucidates why Safir’s practice is equally committed to the manual and digital manipulation of images. While the manual manipulations of the fabric turn the traditionally visual relation to images into a physical encounter, the digital manipulations problematize the legibility and immediacy of the photographs.

Positioning her works in staunch opposition to the flatness, transparency, and immediacy of digital interfaces, Safir’s contestatory spirit echoes artists like Louise Bourgeois and Eva Hesse who opted to create soft, manually produced sculptures at a time where the dominance of Minimalism preached for hard industrially-produced works. Set at Baxter Street at Camera Club New York, the storied artist-run nonprofit space founded in 1884 and historically worked with figures such as Alfred Stieglitz, Paul Strand, and Berenice Abbot, Safir’s works are set in dialogue with the history of photography. They are also a testimony to the breadth and reach of lens-based practices today. Emphasizing the materiality and presence of images in space, their contested relation to labor and gender, and their inherent opacity, Safir’s striking panels, reveal how opacity may be mobilized to unveil the dark undertones that normally remain hidden.

Emma Safir: Glitches & Veils continues at Baxter St at Camera Club New York until March 26. The exhibition was curated by Sally Eaves Hughes.

—

Carlota Ortiz Monasterio is an art historian and curator from Mexico currently pursuing an MA in Modern and Contemporary Art at Columbia University.

The Writer Apart

by Victoria Horrocks

In 1974, Toni Morrison collaged together The Black Book. The book explored the history and experience of Black people in the United States and was published by Random House, where Morrison had famously been an editor. It functioned as a literary archive consisting of historical documents, artwork, ephemera, photography, and more.

In 2022, Toni Morrison’s Black Book, curated by Pulitzer Prize-winning author and critic Hilton Als, likewise presented the viewer with a dynamic visual and textual study of Black history, with Morrison the focal point. Centered quite literally in the exhibition, photographs and archival material document the writer’s biography in the first part of Als’s exhibitionary collage at David Zwirner Gallery in New York City. With four other galleries gathered around this historical centerpiece, Morrison’s life—her work and her biography—remained the subject of the exhibition, even if the work of prominent artists, such as Kerry James Marshall, Jacob Lawrence, Amy Sillman, James Van Der Zee, Chris Ofili, and more, lined the gallery’s white-cube walls. Although Morrison is quoted in the exhibition as having said, “in paintings, I can see scenes that connect with words for me,” Als went beyond the medium of painting to illustrate the lasting impact of Morrison’s work.

Featuring found objects and ephemera dating from the early to mid-twentieth century, Als populated the galleries of the show with clothing, children’s toys, and furniture. Among these objects, a reader of Morrison’s novels would have found tokens from Morrison’s texts, such as Shirley Temple Doll (1930s) on the floor of the back gallery. The doll sat across from a found antique cabinet with glass doors, behind which sat a blue ceramic mug, Shirley Temple Child’s Cup (1930s-40s), featuring the iconic face of the child actor. In Morrison’s novel The Bluest Eye (1970), young female protagonist Pecola wrestles with hegemonic white beauty standards and looks to Shirley Temple as the paragon of white, blue-eyed female youth. Beyond the object and text in dialogue here, the doll’s presence also recalls the “Doll Test,” a study conducted by social psychologist Kenneth Clark in the 1940s. The study demonstrated the negative effect of segregation on Black children’s self-image and self-esteem—findings later used in Brown v. Board of Education (1954) to end state-mandated segregation in schools. This pairing is just one example of how lines of influence are drawn, and individual experiences are abstracted in the exhibition. Significantly, this discursive work is displayed amidst resonant excerpts of Morrison’s novels, printed on the walls in between works of art, asserting that they, too, are works of art in their own right.

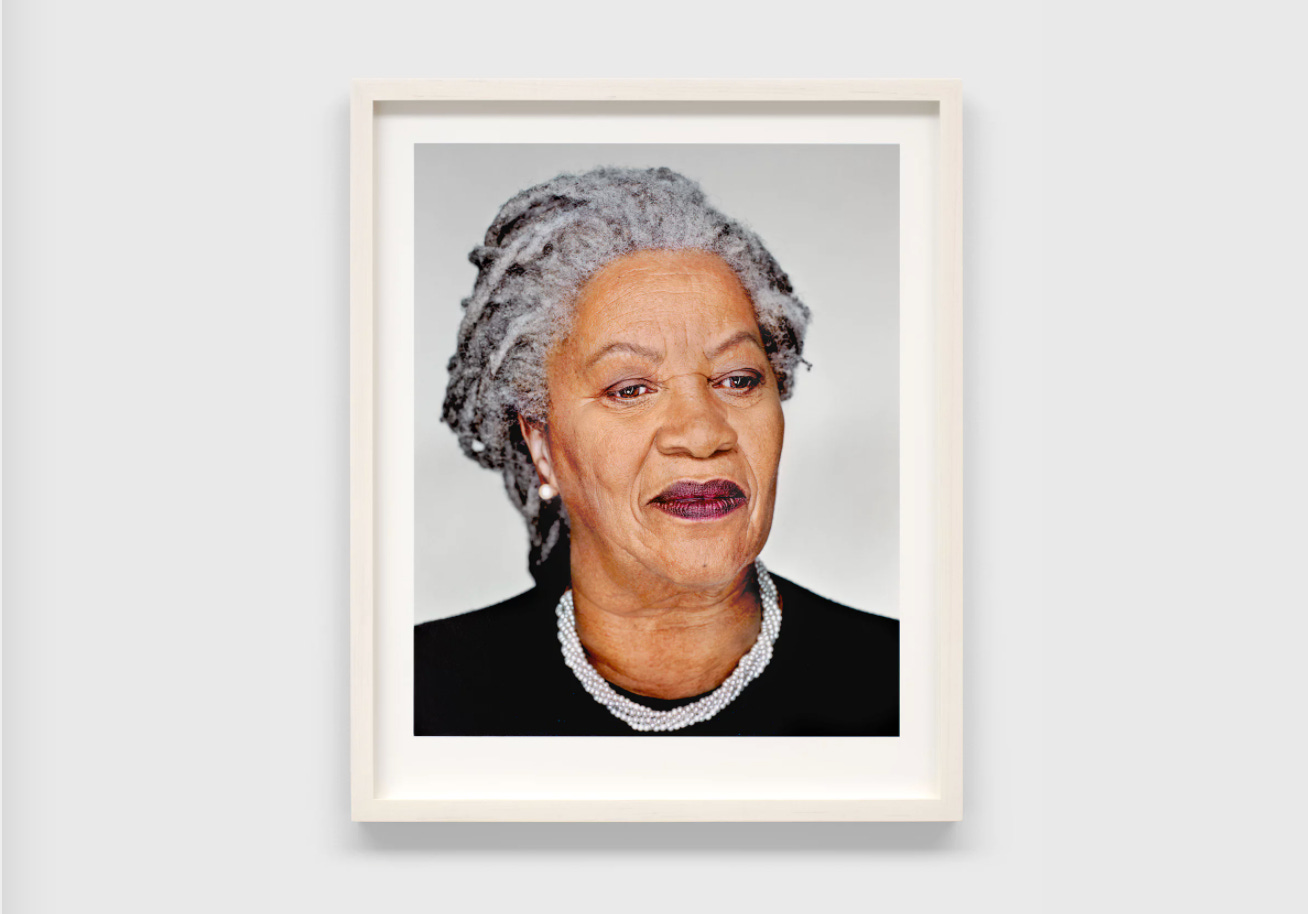

Despite its visual components, Als’s exhibition keeps literary texts central to the show, like scattered signposts guiding the viewer through this avenue of Black history. For example, in a syntactical triptych, a quotation from Morrison’s 1988 lecture on Beloved marks one wall opposite a photographic portrait of the author by Martin Schoeller, Toni Morrison; Grand View-on-Hudson, NY (2003). A green steel bench titled A Bench for Toni Morrison (n.d.) sat between them, occupying the available space in the gallery. The quotation reads:

There is no place you or I can go, to think about or not think about. To summon the presences of, or recollect the absences of slaves… There’s no small bench by the road. There is not even a tree scored, an initial that I can visit or you can visit in Charleston or Savannah or New York or Providence, or better still, on the banks of the Mississippi. And because such a place doesn’t exist…the book had to.

In this exhibition, Als presents us with a book that is not only the immediate text in Morrison’s novels; he created a conceptual “book” in the form of the show itself. Beyond memorial, this visual book made of the exhibition creates the same sort of place that Morrison’s novels did: a space for memory, communicating experience, and summoning presences and absences.

Still, while a book might suggest a beginning, middle, and end—the narrative structure we have all come to expect of a hardcover or paperback—this exhibitionary book denounces traditional narrative organization and instead breaks open plot, reconceives of fiction, and manages to assemble both a retrospective and a poetic ode to the writer. Als’s Black Book constructs a history localized around a central figure, providing the viewer with a fresh, generative mode of history-telling that significantly defines its own time and space. It leans on Morrison’s life and work, constituting multiple narratives—both fictional and lived—to source Black history and womanhood. Importantly, what is a biography of the writer, a different sort of artist, is also a certain construction of history. This method and framework for an exhibition make the exciting claim that an individual’s history is inherently collective and flexible beyond its own spatial and temporal specificity. It reminds us that we can understand history through the register of individual experience, a more compelling and arguably more authentic way than the sterile, one-dimensional history textbook.

What was most striking to me about A Bench for Toni Morrison is its call to Morrison’s own presence in the gallery. While the viewer browsed many photographs and representations of the writer throughout the show, the bench summoned a significant presence. Als seemed to ask Morrison to join us in this profound reflection on the writer’s life and impact, which included both her historical life and the one consisting of the artists whom she has touched creatively across time, including before, during, and after her own life. Dawning a regal wisdom, with grayed hair pulled back and a magenta lip, Morrison’s face in Schoeller’s portrait, facing the bench, stared directly at the imagined sitter. With the photograph placed at eye-level, showing her eyes gazing in the bench’s direction, the viewer was asked to imagine taking a seat across from Morrison to grapple with the charged presences and absences she did in her novels, then manifest in the gallery. A snippet of text from Morrison’s A Mercy (2008) printed near the bench read: “I walk alone except for the eyes that join me on my journey…I am a thing apart.” Als significantly does not suggest that Morrison is looking down on us from above, but that she is instead right here with us—in the gallery and in our contemporary lives—fractured, prismatic, and reflective in our eyes now, having indelibly shaped how we see our present, and future, and our past.

—

Victoria Horrocks is a writer and art historian currently pursuing her MA in Modern and Contemporary Art at Columbia University.

Phantom Histories in Arturo Kameya’s Who can afford to feed more ghosts?

by Darcy Lannen Olmstead

Arturo Kameya (b. 1984, Lima) explores history as a staged thing. The haunting set of Who can afford to feed more ghosts?, conflates time and space into a multidimensional museum experience. Histories coexist in the installation: the death of an immigrant, the resurrection of a vampire, the COVID-19 pandemic’s effect on the Peruvian population, a scandal surrounding a corrupt government official, and a scene from a Japanese Obon ritual. These stories haunt the work simultaneously, but each is hard to tease out without careful reading, their connection existing only in that space beyond the grave. By conflating multiple narratives, Kameya questions the processes of history-making. How do stories fade into ghosts, fragments of their original conception? How many ghosts have been created across the course of history? Who can afford to feed so many histories at once?

Kameya’s interest in layered temporalities drew me to the “assemblage” theory of Kajri Jain. The assemblage allows for an open historical narrative, something that, like Kameya’s installation, is deeply aware of how unstable stories and objects truly are. The assemblage allows art to breathe. Jain writes that her methodology “intensifies art history’s focus on the object, this time not just as a bounded and given entity that is a node in networks of circulation, but as itself a bundle of multiple interlinked processes… an assemblage. Here, as with cultures and individual subjects, the object is seen not as stable… but as a field of moving forces...” Kameya himself is working within the sculptural history of an assemblage, combining mediums and found objects. My essay serves to reflect his tactics by centering the installation itself and layering on the multiple narratives and histories that Kameya presents within the context of his personal experience.

A séance sits at the very center of the work. Two faceless figures painted on wood cut-outs sit around a table dotted with found objects that Kameya claims are “witnesses to history, material evidence of the past.” The scene is surrounded by faded paintings filled with histories of Peru. Painted in clay powder, they evoke the adobe brick houses the artist grew up in. The central figures appear to stretch their arms and crack their backs in preparation for a seance. Elderly, tired—they are preparing to do something they’ve done time and time again. A sense of heavy weariness lingers over the scene. Until, suddenly, a fish flops in a bamboo steamer. A bubble of foam drips from a dog’s mouth. A sardine can oscillates across the dinner table on its own. The viewer is brought out of their trance. Histories become resurrected, but only periodically.

It is impossible to research every aspect of the installation fully. Kameya notes that relating to the content within each image is an impossible feat; instead, he attempts to “[transmit] the tone of the work.” By that, the artist means “to engage in the same frequency with the viewers or at least with some of them.” Kameya was vague about what this tone might be. The work sways between humorous, solemn, and even angry emotions. He pointed to the rabid dog snarling in the corner of the scene: “the dog is a reference to the fear of stray dogs with rabies—a common fear in the 90s in Lima. The word ‘rabies,’ Rabia in Spanish, has two meanings, illness and rage or to be enraged. So I wanted to have a character or element there that was both sick and enraged.” Yet the stories Kameya centers his work on are often ridiculous, almost laughable. He explores humor as a coping mechanism, something that often masks a deeper sorrow.

The oldest ghost central to Who can afford to feed more ghosts? is that of Sarah Ellen Roberts. She peers from a photograph tucked into the corner of a grave marker in a miniature painting hung above the outline of a grave. However, the name on the marker has been obscured and reflects a male onlooker in a blue collared shirt. Despite similarities, this isn’t Roberts’s real grave. It is a mass grave, a fusion of all the graves for all those dead commemorated by Kameya in this single installation. Yet Roberts’s is the only grave that has become a true icon in Peru.

In 1913, a British man named John Roberts appeared in the city of Pisco carrying the coffin of his dead wife. Locals assumed she had been convicted of witchcraft and was forbidden from being buried in her homeland. In England, Sarah had apparently been caught sucking the blood of a small child, and Pisco’s inhabitants were convinced that she still breathed beneath the soil. In 1993, on the anniversary of Roberts’ death, a vampirologist appeared on a popular talk show to sound the alarms that Sarah would resurrect within the week. Thousands flocked to her grave with rosaries, garlic, and holy water. When she failed to return, it was accepted that their prayers had kept her asleep. In animating the food offering left on Robert’s grave, Kameya emphasizes how Roberts’ story—her ghost—has been continuously resurrected over the course of a century.

The man with comically long nails and a rosary standing in front of Roberts’ grave is intended to be an object of ridicule. He is painted as the superstitious onlooker, waiting defiantly for the vampiress to rise. Yet time has been conflated in this scene—he could be looking upon the grave of a vampire or a saint. He is a museum visitor but also the ghost of an undead man, likely the mayor of Tantará, Jaime Rolando Urbina Torres. Like Roberts, Torres made national headlines from within a coffin. In May of 2020, the mayor was out drinking with friends, evading national lockdown measures. Police reported that he had been found pretending to be dead in a coffin reserved for one of the thousands affected by COVID-19. Kameya heard this story while living as an expatriate. Despite often drawing upon scenes from his homeland, the artist lives and works in Amsterdam, and his work is most often shown outside Peru. The artist’s own distance from the stories he covers allows him to focus on questions of universality, noting he “would have made the work a bit different if it was presented in Peru because I could have been a bit more cryptic since most of the people there are familiar with some of the images and symbols I used.” Kameya feeds his ghosts from afar, using only remnants of their original stories.

In the Japanese-Peruvian community, feeding ghosts is a common practice of Kameya’s upbringing. Around the room, paintings of make-shift altars with food offerings represent a practice common during the Obon festival, or “Japanese day of the dead.” For one, the lotus-shaped citrus fruit alludes to the Buddhist holiday; it is a treat to nourish the souls of one’s ancestors. Yet some of the altars Kameya paints take on a contemporary edge. The central painting in the room features the Virgin Mary standing atop a plastic crate, surrounded by bottles and a takeout container whose fries have been picked at, likely by the bird floating behind it. Mother Mary is illuminated by a moon-like ring light that cradles an iPhone. It is a Buddhist altar centered upon Catholic and contemporary imagery. These contrasting elements speak to the resilience of the Japanese community within a hostile environment such as Peru.

In the 1990s, during Kameya’s childhood in Lima and the election of Japanese-Peruvian President Alberto Fujimori, racial tensions were high. Most of the Japanese community had refused to vote for the first non-white presidential candidate. “Some Japanese-Peruvians reported that their businesses were attacked during the election campaign; others were denied entry to exclusive discos and clubs on racial grounds.” Throughout Who can afford to feed more ghosts?, and Kameya’s oeuvre as a whole, are many references to this period in Lima’s history. For example, the installation features a small “Provincial 90” poster from Fujimori’s 1990 election campaign. The space revolves around the Japanese-Peruvian communities of his youth, yet their ghosts appear in fleeting moments. Their stories require extensive research on the part of the typical visitor. They are never fully present, merely scraps of history.

This difficulty of transmission is crucial to Kameya’s installation. Despite hoping to find cultural links, or, ways of communicating on “the same frequency with the viewers,” his installation remains vague, occasionally distracting. For one, the animated elements often divert the viewer’s attention away from fully engaging with each tableau. The installation participates in a theater of miscommunication. The visitor floating through the work, haunting Kameya’s installation, activates it. Kameya draws upon his own experiences, but his installation serves to cut across temporalities into the realm of any possible viewer.

As a viewer, my own narrative, therefore, layers itself into the greater assemblage of Who can afford to feed more ghosts? despite my disconnect from Lima. To justify her assemblage theory, Jain asks why we should “persist in reading [works of art] in terms of periods, nations, or cultures” rather than taking art history beyond the categories so fundamental to European colonialism. Kameya draws upon his own culture, but only to highlight how disparate cultures can be visually linked. While he focuses on narratives set in Peru, he created this work in his studio in Amsterdam. It is currently being displayed in New York City and being written about by a girl from Arkansas. Kameya emphasizes how stories are open-ended assemblages in themselves—they can resurface throughout time and space, despite cultural or national conditions.

—

Darcy Olmstead is a writer and art historian currently based in New York City. She recently received her BA in Art History from Washington and Lee University and is currently a master’s candidate in Modern and Contemporary Art History at Columbia University.

“Arturo Kameya.” GRIMM Gallery. Accessed November 2021. https://grimmgallery.com/artists/74-arturo-kameya/

“Arturo Kameya Drylands.” Dordrechts Museum. Accessed November 2021. https://www.dordrechtsmuseum.nl/english/arturo-kameya-drylands/

Fried, Michael. “Art and Objecthood.” Artforum (1967). Reprinted in Minimal Art: A Critical Anthology. Ed. Gregory Battcock. (Berkley: University of California Press, 1995). pg. 116-147.

Garth, John. “‘Vampire’ haunting Peruvian City is unmasked … as a British holidaymaker.” Daily Mail. May 22, 2009.

Jain, Kajri. Gods in the Time of Democracy. (Durham: Duke University Press, 2021).

Jensen, K. Thor. “A mayor in Peru was accused of lying in a coffin and pretending to be dead to avoid being caught disobeying lockdown orders.” Insider. May 21, 2020.

Kameya, Arturo. Interview by Darcy Olmstead. December 11, 2021.

Takenaka, Ayumi. “The Japanese in Peru: History of Immigration, Settlement, and Racialization.” Latin American Perspectives. Vol. 31, No. 3: May 2004.

“Who can afford to feed more ghosts?” Soft Water Hard Stone. The New Museum. New York City, Fall 2021.

Please follow us on Twitter and Instagram (@poltern_) for updates and share our newsletter with anyone who might be interested.