Welcome to the fourteenth Poltern Newsletter.

This month’s issue includes a pertinent and playful list of exhibtion-related trend predictions for the new year written by Hannah Kressel; a compassionate reflection on multiplicity and parts of a whole in response to Jasper Johns’s In Memory of My Feelings—Frank O’Hara (as seen in the artist’s Whitney retrospective, Mind/Mirror) by Victoria Horrocks; an interview between UK-based visual artist Alexander Stavrou (Ruskin MFA ‘21) and Leander Pöhls on the roles and responsibilities of digital art.

If you have any questions or comments, please do reach out to us by responding to this email or writing us at polternmag@gmail.com.

Thank you for being here.

The Poltern Team

2022 Trend Predictions

by Hannah Kressel

OUT: Exhibition hashtags

While they may have been cute in the beginning, these kitschy one-liners won’t survive in a year primed for social media cleanses. After nearly two years of virtual talks, shows, walkthroughs, and concerts we’re worn out! We want to step away from our phones and just be with the work. We don’t want the reminder of distracting hashtags and the pressure to post our ‘experience.’ And, anyways, hashtags are essentializing and rarely capture anything to do with the work they reference. Anyone remember when Vienna’s Kunsthistorisches Museum tried to make #barockstars happen? No, thank you.

IN: Instagram-exclusive shows

Although hashtags for brick-and-mortar shows may be getting tossed with the crocks (please let that revival be over), fully virtual exhibitions are in. Expect exhibitions which exist solely within the metaverse. Although people are itching to rejoin in-person events, online exhibitions allow the flexibility and fun we expect to frame 2022. These exhibitions may manifest in 24-hour Instagram stories (perhaps, on exclusive to Close Friends lists), may warrant their own specific accounts, or dare we suggest … Tiktok exhibitions? However they develop, these shows are sure to be fresh, sweeping, and a touch chaotic.

IN: Fermented flair

As 2020 made bread bakers of us all, 2022 will see these same concerns: of temperature, of yeast, of bubbly frothy flair, but this time out of our kitchens and inside gallery spaces. Kombucha served upon entry into the gallery, yeasty mixtures of flour and water dripping down canvas, and all to the soundtrack of a burping, belching starter. Too much? Check out the work of Sean Nash, Leila Nadir and Cary Peppermint, or Nicki Green and maybe you’ll change your mind. The metaphorical possibilities of fermentation practices are vast—considerations of transitioning, digesting, and dis-integrating are key—and we are excited to see how these themes develop and take center stage in the year to come.

OUT: Overdone merch

No more tote bags! We are, quite literally, drowning in bags. While the first few tote bags were fun and quite useful, a person can only carry so many winter radishes from the farmer’s market. And, more importantly, the overabundance of show merchandise is bad for the environment. If owning a reusable bag keeps you from taking plastic ones at the store that’s wonderful, but owning upwards of six or seven? That’s overkill. We hope to see new ways to share our excitement over great art … beeswax wraps maybe?

IN: Appropriate seating in galleries

Gone are the days of discomfort in the museum and other art spaces. In 2022 we want to see art become more accessible and that begins with making the spaces in which we house art more accessible. This means obvious and appropriate seating in galleries. Gallery stools are not appropriate for all bodies nor are they safe for everyone to sit on, considering they typically do not have any back support. And, if that doesn’t convince you, try sitting in front of a work of art rather than standing—the difference is breathtaking. While we understand that many art spaces struggle with constraints of space and that the work’s safety is of the utmost importance, the accessibility of the physical gallery space must be reckoned with before other accessibility concerns can begin to take hold.

OUT: Interactive for the sake of being interactive

Honestly, we just miss normal exhibitions. While COVID closures are out of our control, we hope that when normalcy returns once more, it is the art that is focused on—not a perfectly lit, Instagrammable room. In 2022, we hope to see museums re-center around the art they exhibit rather than fussing over interactivity and losing sight of what is on the wall. While interactivity, of course, has a place in art in 2022—let that interactivity be guided by artist rather than curator.

IN: Museum unionization

As COVID-19 initially brought to light and continues to remind us, job insecurity is an issue that plagues all cultural institutions. Art workers have long faced opaque expectations, conditions, and compensation in the workplace, an issue only intensified by the forced closures of many cultural institutions brought on by the pandemic. Now, two years into the pandemic, while COVID-19 intensifies again, art workers are intensifying with it. After suffering indefinite furlough and layoffs, museum workers are speaking up about their rights and are unionizing. Looking to the Whitney, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, and the Guggenheim as examples, we hope to see more museum unionization in 2022.

—

Hannah Kressel is a writer and art historian currently based in New York City. She recently received her MSt in the History of Art and Visual Culture from the University of Oxford.

A Scene of His Selves

by Victoria Horrocks

By the end of the 1950s, the artist Jasper Johns was obsessed with multiples. Johns’s retrospective Mind/Mirror, at the Whitney Museum of American Art, emphasizes a delectable and compelling repetition of basic information throughout his work, such as flags, numerals, letters, objects, body parts, and other figures. What do we make of them? Art critic Jason Farago writes that many of Johns’s paintings “come across, at first, as a closed circuit of intellectual puzzles.” Perhaps this is what drew me so closely to the works on display in Mind/Mirror. As a lover of jigsaws, crosswords, etc., I posed as detective in the galleries—connecting the proverbial dots and extracting hidden meanings.

Somewhere towards the middle of this exhibition hangs Johns’s painting titled In Memory of My Feelings—Frank O’Hara. The painting is oil on two canvases attached with two hinges at the center. The proportions of the composition resemble those of the American flag, locating this painting among Johns’s “flag-paintings,” which had propelled him to fame by the time he completed this work in 1961. Beyond its proportions, however, little is recognizable of a traditional American flag. Rather than stars and stripes, Johns covers the painting in abstract marks made in shades of blue and gray. The title and his own name appear stenciled, in typical Johns fashion, at the base of the painting, and a spoon and fork are suspended together by a wire on the canvas’s surface.

According to the sparse wall text, In Memory of My Feelings—Frank O’Hara is an “intensely mournful painting in the wake of his breakup with Robert Rauschenberg. He titled it after an elegiac poem written by Frank O’Hara, which laments the death of former selves and emotions.” Amidst expressionist lines and abstracted forms, however, it seemed to me that there was more at stake in this painting than a sweeping autobiography or what meets the eye. O’Hara and Johns were close friends who allude to one another in their respective work—O’Hara in poetry and Johns in his art practice. This relationship in itself compels further exploration as to the meaning it might impart on the painting. Even in Farago’s latest “close read” article in the New York Times last week, little attention has been paid to the integration of O’Hara’s poetics via Johns’s brush. After all, O’Hara’s name sits prominently in the title of the work and on the canvas itself. Reading a creative dialogue within the painting, I wondered what it might mean for Johns to express himself, albeit reservedly, by means of his friends’ words.

O’Hara’s poem “In Memory of My Feelings” was written in 1956 and dedicated to O’Hara’s close friend Grace Hartigan. The poem describes a fragmentation and subsequent reintegration of the inner self, a self that threatens continually to dissipate under external forces. Significantly, the poem opens with the phrase: “My quietness has a man in it, he is transparent.” In this line, O’Hara declares his inner self something visible and identifiable before proceeding to elaborate on his “several likenesses, like stars and years, like numerals/My quietness has a number of naked selves,/so many pistols I have borrowed to protect myselves. This man that O’Hara makes “transparent” to his reader in poetry is multiple and ever-evolving. In the following five sections, O’Hara continues to grapple with this concept and concludes:

I have forgotten my loves, and chiefly that one, the cancerous

statue which my body could no longer contain,

against my will

against my love

become art,

I could not change it into history

and so remember it,

and I have lost what is always and everywhere

present, the scene of my selves

The end of the poem describes the constant passing away of one identity after another, importantly becoming art—something without language and something ineffable. Identities become some “scene” that encapsulates the nonbinary, expansive, and turbulent self that resists singular definition.

Johns’s painting does not illustrate O’Hara’s poem, but it does draw on this dissolution of self, of identity, and the complexity of feeling. Art historian Fred Orton suggests that in Johns’s painting, “the ‘feelings’ are there on the surface of the two canvases and that the ‘man in it’ is underneath.” The gray brushstrokes that dominate the canvas and mark the white ground are not the direct expression of feelings. Instead, they are signifiers of mourning. As Russell Ferguson argues, the markings can be read as referring to an unmediated association of feelings and facture. Yet these feelings are still contained across two canvases, held together by two metal hinges. Exposing a dual meaning, here, he writes, “The hinged construction suggests the possibility of two elements breaking apart completely, yet simultaneously holds out the opposite option: that of coming together completely.” The hinges produce a doubleness in the painting, evocative of multiple couples or pairs. Provocatively, Farago suggests that the canvases “start to feel like lovers in a tomb.”

The spoon and fork echo this doubleness as they hang by a wire on the left canvas. The repetition of doubles opens up multiple significances for the “feelings” or “selves” that are represented in the painting. As Orton writes, the stenciled title running along the painting’s lower edge, which includes O’Hara’s name, acts as another “hinge,” so to speak, between the painting and O’Hara’s poem. This dialogue between O’Hara and Johns within the piece raises further integral pairs within the work, such as image and text, and painter and poet. Recalling O’Hara’s poem, Johns likewise includes several selves—arguably both literal and figurative—in his painting. While the wall text considers the paired objects emblematic of Johns and Rauschenberg themselves, it would be unlike Johns to lay his inner life so bare, as a poetic object quite literally exposed and protruding from the surface of the canvas.

Perhaps Johns does grieve his relationship to Rauschenberg, as is suggested in the wall text. I sense, too, that Johns mourns one of his selves, a version of him understood in relation to a lover who is no longer his partner. Within In Memory of My Feelings—Frank O’Hara, these implicated selves resonate between both Johns and himself, as well as between himself and others. Relational dynamics exist within the painting in the pairing of Johns and O’Hara, in Johns’s relationship to his displaced identity, and in some engagement between Johns and the viewer. While potentially a representation of the lovers, the spoon and fork also indexically refer to an absence of a consuming body; the shadow they cast may implicate this removed form, as art historian Alexandra Gold suggests. As such, the spoon and fork signal significant absence, and, even within the pairing, the spoon subsumes the fork, further suggesting a mechanics of obstruction at play in the piece.

Significantly, where O’Hara claims, “My quietness has a man in it, he is transparent,” Johns instead obfuscates his feelings, making them anything but transparent. He is, as Farago calls him, “a master of withholding.” Lines blur and cross each other, and even forms, like the American flag, are distorted to further deny identification. Still, the painting quite literally has a man in it, with X-rays of the painting revealing the stenciled lettering of “DEAD MAN” and the representation of a human skull beneath the topmost layer of paint, unseeable to the eye. Rather than O’Hara’s nakedness and vulnerability, Johns conveys a defensiveness, hiding the inner self from view. In his own words, “I didn’t want my work to be an exposure of my feelings.”

Are we to think that the “DEAD MAN” is Johns himself, entombed within the picture plane? Does it act as a doubled signature, located just behind the stenciled “J. Johns” on the surface? Such readings would affirm Orton’s assertion that the feelings sit on the surface of the painting, obscuring a man “in it,” evoking O’Hara’s poem. Or, is this the absented body that once made use of the spoon and fork, now dead and buried, within the painting?

In any case, the body at hand is made invisible, leaving behind only feelings, just as, in O’Hara’s poem, the existence of multiple selves dissolves a singular identity and promotes abstraction of the self beyond the tangible physical body, “against my will/against my love” to “become art.” Relying on O’Hara’s words and the conceptions of identity brought forth in “In Memory of My Feelings,” Johns seems to further distance us from his own inner life by diverting us from his own painting and towards the work of a friend he deeply admired. While, yes, poetry can sometimes encapsulate our feelings on our behalf, even helping us to understand them, Johns utilizes it here to create an abstract self-portrait. Ironically, this portrait refuses his self, or his selves, completely.

If the key to understanding Johns’s painting is turning away from the painting to ascertain meanings encoded in language elsewhere, then it might seem as if Johns actively reminds us that we are not meant to access his inner life. Still, often it is our friends who can know us better than we know ourselves. They stand outside of us, looking in, just as the viewer of In Memory of My Feelings—Frank O’Hara peers into the painting. In the best of cases, our friends, through reflection and council, can provide critical language when we feel ourselves to be blurred. As our sense of self inevitably becomes challenged and turns nascent, our friends can affirm to us who we are. By communicating with Frank O’Hara’s words, Johns’s painting becomes one of friendship, of love, and of his multiple selves.

—

Anfam, David. Abstract Expressionism (London: Thames & Hudson, 1990).

Farago, Jacob. “How a Gray Painting Can Break Your Heart.” New York Times (New York, NY), Jan. 16, 2022.

Ferguson, Russell. In Memory of My Feelings—Frank O’Hara and American Art (London: University of California Press, 1999).

Gold, Alexandra. “Coming Unhinged: Art and Body in Frank O’Hara and Jasper Johns.” Interdisciplinary Literary Studies 17, no. 3 (2015): 330–51.

O’Hara, Frank. Frank O’Hara: Selected Poems, ed. Mark Ford (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2008).

Orton, Fred. Figuring Jasper Johns (London: Reaktion Books, 1994).

—

Victoria Horrocks is currently an MA Candidate at Columbia University in New York. She recently received her MSt in the History of Art and Visual Culture from the University of Oxford.

Artist Interview with Alexander Stavrou

By Leander Pöhls

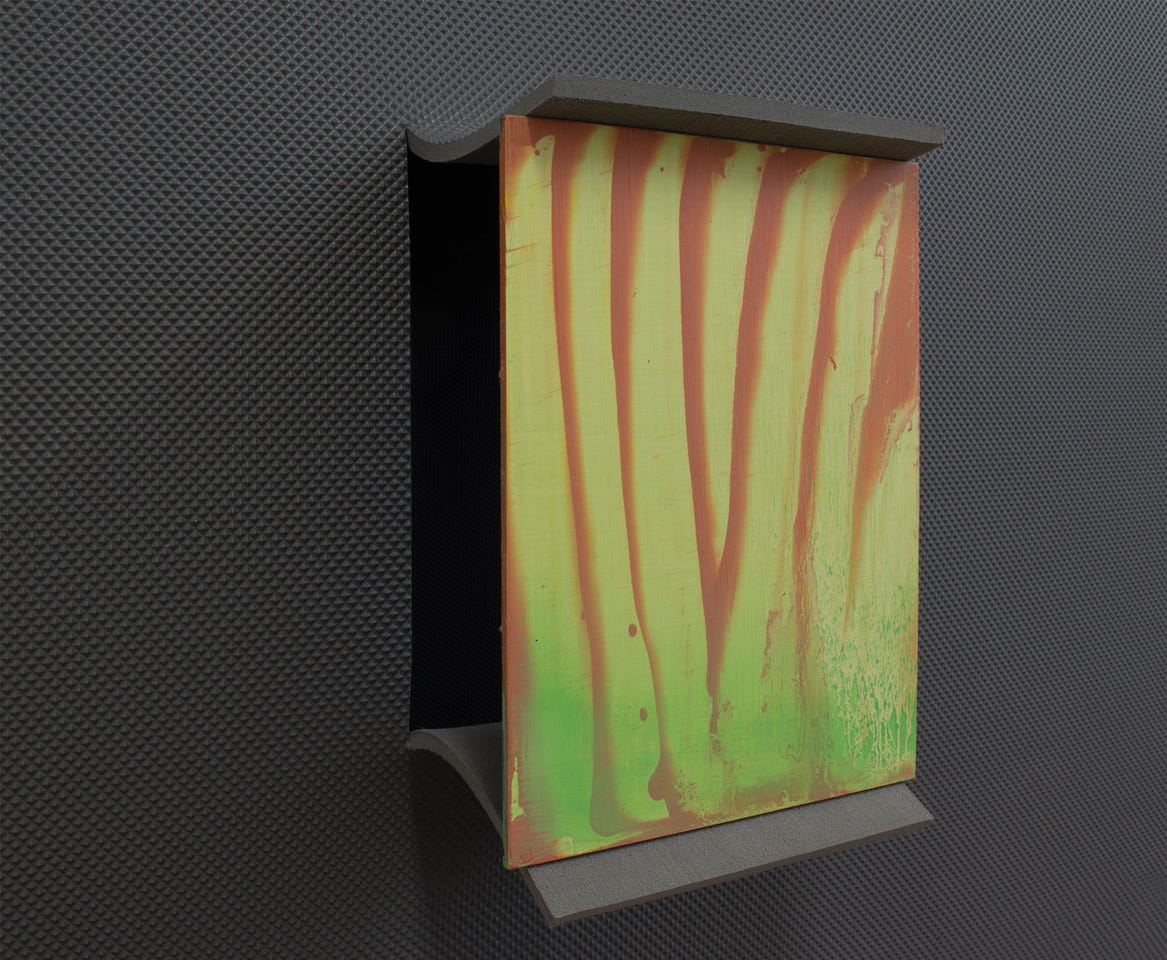

Leander: I would like to begin with a development I observed regarding the techniques you use in your artistic practice. While you primarily worked with painting in the last few years, you have recently turned to digital film. Would you agree that digital practices have become increasingly important for your work and, if so, what draws you to the exploration of these methods?

Alexander: I have definitely started to work more with digital film. I feel as if it is a way of working that I access through painting—as if painting is a portal of sorts. The digital work is certainly becoming more important to me, but I don’t think that it displaces painting within the overall practice. Both strands are hopefully feeding into each other, which allows me to continue to play and question in a haptic way.

I enjoy this haptic way of exploring the formal and material aspects of painting and the painted object, be it a variation of oil on panel or on canvas. The quadrilateral of the picture plane (or the edges of the panel/canvas) is, for me, one of the ever-present referents of making pictures or paintings. It feels impossible for me to get away from, even if you make something which is utterly different from a quadrilateral, it still seems to come back to the fact that it is not that usual frame or window. I think this may also go for surfaces.

I see this square or rectangular boundary as a referent that acknowledges its own limitation and freedom. I have also often found the inherent grid of a computer screen to share aspects of this quality of being a referent with a limitation/freedom.

As such, it felt natural to question and play with the computer screen, with its digital lozenges and the grid of computer imaging programs, in a very similar way that I do when making paintings. I find it very difficult to clearly put it across with words—there are these ways of working, (possibly deriving from the same urge), at play in these two very different but closely related forms of media within my overall practice.

L: I find it very interesting how you compare the quadrilateral of the canvas to the electrical grids of computer screens. Many of your works, including both your films and paintings, seem indeed to play with and counteract the spatial orders they are positioned in, be it a canvas, a panel, or a digital screen. For me, your work presents a dance of objects slipping in and out of their given limitations. It seems as if the referents in your images wish to “free” themselves from their spatial imprisonment. In this sense, I wonder if you would describe your artistic motivation as a kind of “ontological desire”—a desire to break down and investigate the very (im-)possibility of artistic expression to escape its limiting frames, grids, and patterns? Or would you say that you voluntarily put your objects in spatial confinement to then capture the dialectic between the inside and the outside of their boundaries?

A: I think a bit of both are at play. A work can emerge from the investigative play you’ve mentioned and by putting it in a potentially uncomfortable position, new insights might arise; things we cannot anticipate. A particular situation could reveal a tension the work has with its context. Will it unravel or not? If it does, what becomes of it?

Your use of “(im-)possibility” sums up something about liminality for me; favouring a superposition of sorts as opposed to one or another. Multiplicity rather than rigid fixtures. Just as you said, “dance” and “slipping in and out”, that’s a very helpful way of seeing it! Sometimes the films may feel choreographed and at other times they are falling about the place—or may at least threaten to.

The idea of voluntarily putting a work in a situation that highlights a dialectic of being one side or another of a boundary feels like it points towards a synthetic aspect of boundaries. Of course, limitations are natural and ubiquitous, and while a boundary or an edge is a limitation of a sort, there is also something about them that feels imposed and unreal to me. They feel both problematic and frustratingly necessary at times. It’s strange how something which can be introduced to make a situation more explicit or categorised can also feel so slippery and evasive. Perhaps that is the case with anything dwelled on.

L: What is the role of chance, then, in your work? Would you say that you are sometimes surprised yourself about the performance of this “dance” we have talked about?

A: Sometimes, yes. I’d like it to surprise me. If it was entirely predictable, I don’t think I would find much point in it. So I guess that the role chance plays is one of potential and freedom, how much is a work allowed or perhaps enabled to become something of its own accord? I am inevitably always involved in it, and so there is a tension between myself and the work. When making a work I like to learn, appreciate, gain something new and I don’t think that’s possible if I knew the outcome. If I'm lucky enough for a work to truly surprise me, then maybe it is because it has properly gained its own autonomy and I am taken out of my own preconceived comfort at which point I’d hopefully appreciate something new which I was unable to before.

Maybe that’s why I try to operate and make within a ‘grey mode’ so to speak where concepts are not as fixed as they often seem in everyday experiences, or if they seem stubbornly fixed, they are acknowledged as a concept. In the ‘grey mode’, everything feels like it’s in motion.

L: The dynamic of your work process seems fascinating. Could you give an example of something you have learned recently? Of something that surprised you in the way you mentioned?

A: I think it’s happened with a couple of recent pieces I’ve been working on. Something more profoundly participatory and performative has emerged from them. With Hand Held Device, I suppose the viewer is always being invited to participate in a more hands-on way. Once somebody starts to grip the device, maybe turns the device in their hands, starts walking around a space with it—the work obviously changes—inanimate becomes animate. Its context changes and it is strongly affected by the urges of the participant/viewer. In observing how a viewer or participant moves with Hand Held Device holding Nail Painting (||||), the multiplicity of the work becomes heightened for me. The work holding the work, the viewer holding the work, the street which the viewer come participator is walking through—they each begin to shift through the walls of previous notions I might have thought were previously less permeable. It becomes more difficult to define where/when the work starts and finishes.

And so, Hand Held Device grew into Transit—ranging distances then became more apparent. I hope more things reveal themselves in time…

L: One last question: We started our conversation by talking about your new ways of working. You have been part of the one-year studio-based programme at The Ruskin School of Art and, as you mentioned, a lot of your practices have changed throughout this year. Could you talk a little bit about these changes, both in retrospect and with regards to your future career? How do you think about them, how would you conceptualise them? Do you think of them as parts of an ongoing, ever-changing process of artistic discoveries that will continue to shape and structure your work? Or as single, isolated events that may lead you to a place of stableness, to a persistent set of practices you will draw from in the future? So, how would you register these various changes—thinking of your use of digital media as well as new performative aspects of your work—into your notion of your identity as an artist?

A: I may need to make a new body of work in order to better answer that! I don’t think that they are single and isolated, I’m not sure anything really is. These ways of working are perhaps better

acknowledged as fluctuating globules that may emerge from a vibrating liquid. They aren't separate from each other, nor do they bubble in an entirely predictable fashion. Sometimes the globules bunch together and other times they drift further apart, but they are always connected, possibly entangled.

I still feel very much like someone who fundamentally observes and makes. Both observations and makings are of course related, as everything is revealed to be if or when we pay attention or are somehow allowed to slow down. Then, which relations we dwell on might provide something else. While it feels like something ethereal and dynamic, it too is both stabilising and centring for me, and I hope it continues to be so for a long time to come.

As of now, I’m enjoying the variations which are evident in encounters and moments which may seem repetitive, how these are experienced, perhaps staged, and where they can go.

—

Alexander Stavrou is a visual artist working in London and Oxford. He recently completed his MFA from the Ruskin School of Art at the University of Oxford which was supported by the UK BAME PGT Studentship in the Humanities in partnership with Wadham College. To see more of Alexander’s work please visit his website and Instagram (@alexander_stavrou).

Leander Pöhls is a consultant at METRUM, a consultancy for cultural and other non-profit institutions, and currently based in Munich. He recently completed his MSt in the History of Art and Visual Culture from the University of Oxford.

Please follow us on Twitter and Instagram (@poltern_) for updates and share our newsletter with anyone who might be interested.