Welcome to the twelfth Poltern Newsletter

This month’s issue includes a pensive review of the faces and places on view in JR: Chronicles at Saatchi Gallery by Manuela Gressani; a wistful meditation on symbols and memory prompted by David Driskell: Icons of Nature and History at The Phillips Collection written by Anna Ghadar; an interview between Ruskin MFA Emma Hambly and Georgie Byworth-Morgan on how marine biology, inherited film, and environmental activism shape the artist’s studio practice.

If you have any questions or comments, please do reach out to us by responding to this email or writing us at polternmag@gmail.com.

Thank you for being here.

The Poltern Team

JR: Chronicles at Saatchi Gallery

by Manuela Gressani

I went to see JR: Chronicles at the Saatchi Gallery on one of the first chilly evenings of September; I was wearing shoes that made a very satisfying noise against the hardwood floors of the exhibition, and later, as I walked home, I got drenched by the rain—I remember the sound of my shoes very vividly because it made me unerringly conscious of the space that I was in. Walking from room to room, pausing in front of JR’s work, I could hear the echo of every step, and with every step, the walls around me.

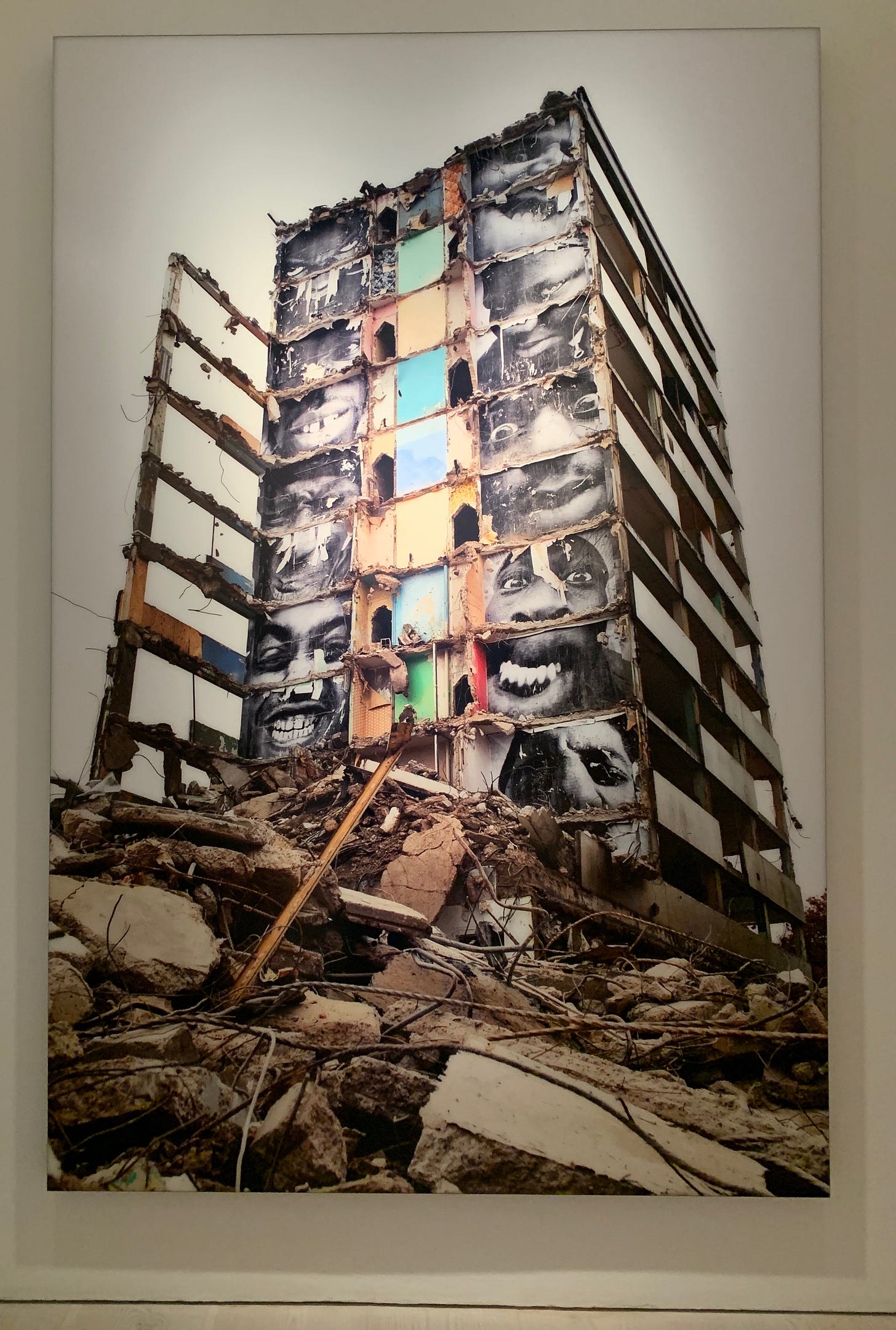

JR focuses on the idea of walls a lot. He started off fascinated by the graffiti and the street artists he encountered across the Parisian suburb of Montfermeil, his home turf. When he found a camera on the metro, he began chasing the atmosphere that surrounded these moments: the adventure of tagging a dark tunnel, the urgency and the need to make a mark, something to say “I was here, I exist”. While these walls of his early photos remain the foundations of his practice, JR’s work now pivots around the physical walls he covers with his large-scale pastings and the metaphorical walls he hopes to dismantle through his photography.

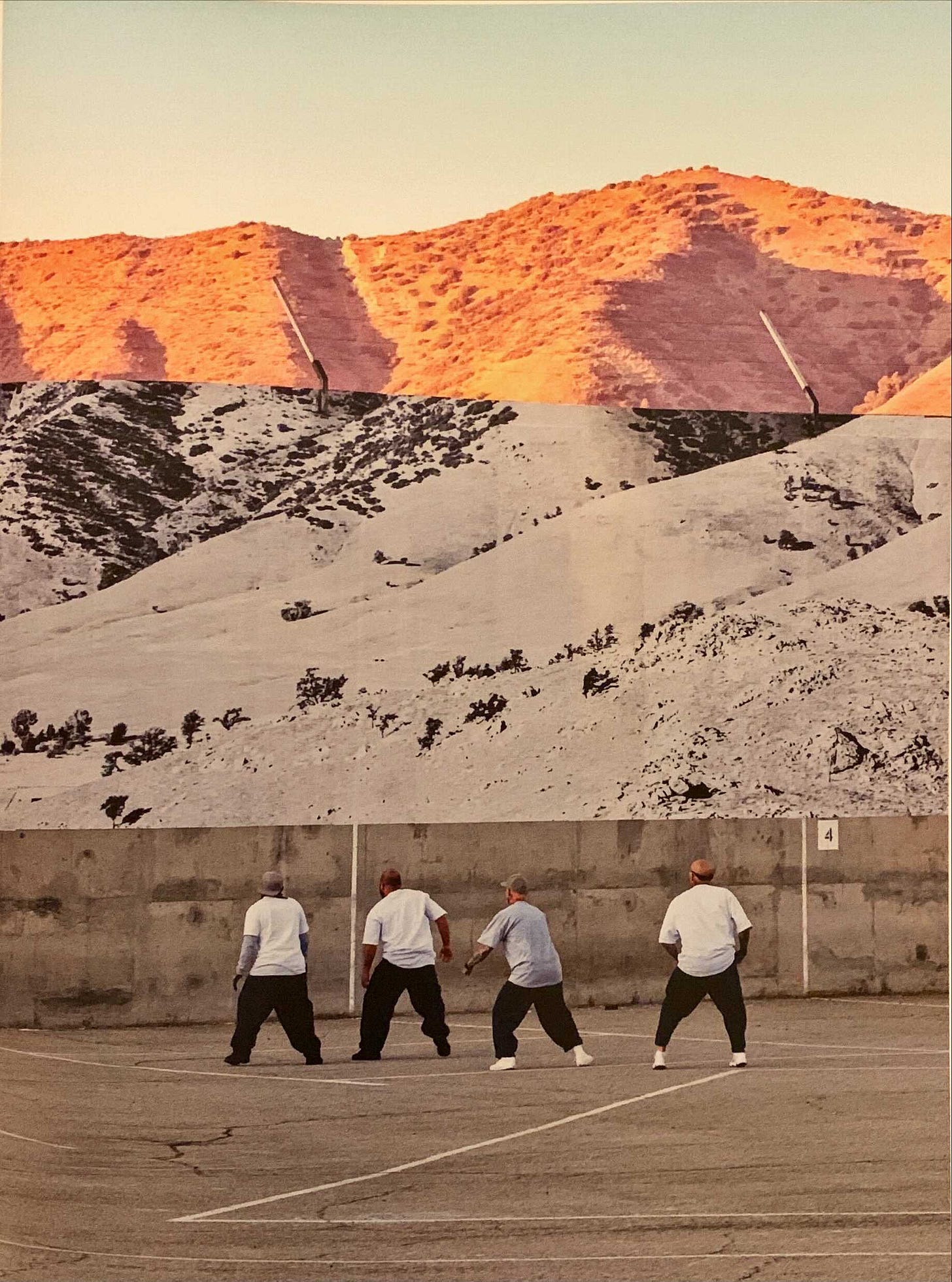

On one of his most recent projects, a two-part installation in the Tehachapi Prison in California, JR worked closely with inmates to create and paste his photos, and in the process, to record the personal stories of the convicts, ex-prisoners, and prison staff. The first part, completed in October 2019, yielded a 48-people group portrait shot from a high angle and pasted onto the courtyard of the high-security prison; the second, finished in February 2020, attempted to visually dissolve its outer walls by pasting images of the surrounding mountains along their inner surface.

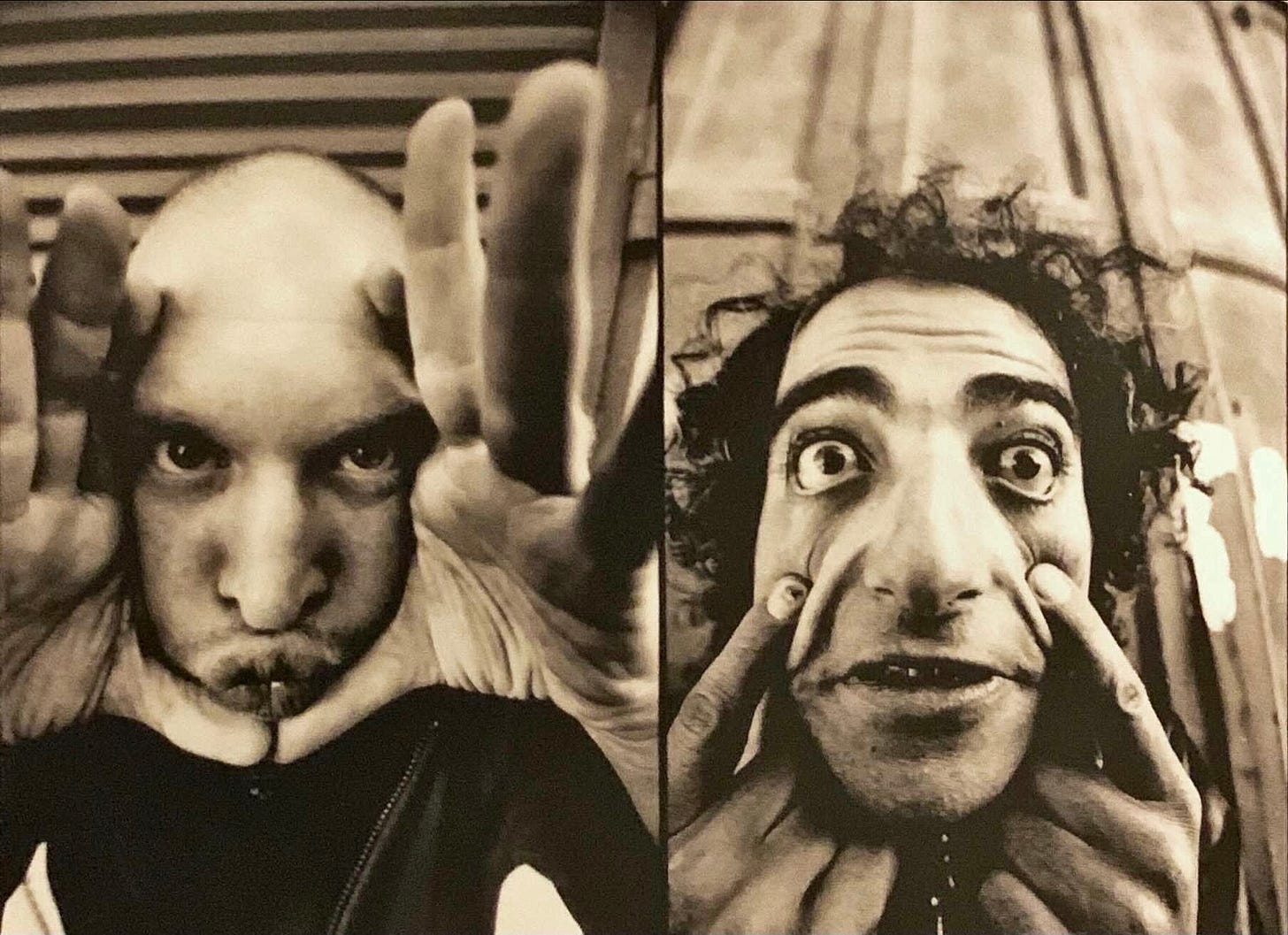

Another project, one that JR embarked upon in 2006, particularly struck a chord with me. Titled Face2Face, it consists of close-up portraits of Israeli and Palestinian people that JR shot while traveling with his friend Marco and then pasted along the separation wall of Bethlehem, Hebron, Jerusalem, Jericho, and Ramallah. His intention, which developed alongside the project, was to highlight the human similarities between the people rather than the differences that fuel the long-standing conflict between the countries. As is the case for the majority of his projects, JR did not seek official authorisation, preferring instead to directly involve the local community. In a recent interview, he recalls the courage he noted in the individuals who consented not only to be photographed, but also to allow (and help) the pasting process: it would be up to them to explain the resulting installations and their unifying hope to strangers and neighbours alike.

A characteristic feature of JR’s portraits, which he produces in abundance across numerous and diverse projects, is that he encourages his sitters to pull a face. These grimaces, ranging from the humorous to the menacing, couple with the slight distortion of JR’s signature 28mm camera to create expressive and unique images of people and, in doing so, give agency back to the individuals and the communities that are often overlooked and marginalised, warped by mainstream media and their accompanying pictures.

Indeed, a lot of JR’s practice can be traced back to his early critique of the ways in which Parisian suburbs and their inhabitants are treated by the police and cast by French TVs and newspapers. His Portrait of a Generation series toyed with these notions as JR’s sitters performed the vandals and delinquents they are labeled as through their exaggerated facial expressions. Looking back, JR sees his methods and formats as an active, although initially subconscious, setting apart from photojournalism: he doesn’t replace their voice with his own, and he definitely doesn’t ‘steal’ images of people from a distance - he couldn’t, his camera needs him to be close to the individuals he shoots.

I found this discourse on identity and voice particularly stimulating. I remember sitting through a couple of lectures about photography during my History of Art BA and the majority of the scholarship we read and discussed tackled these same issues: notions of agency, gaze, and power through the very act of taking photos and the ensuing photographer/photographed dynamic. And, while I’m still wondering whether to agree or disagree with Susan Sontag’s view of tourist photography as a re-enactment and expression of our modern compulsion to work even while on vacation, what has stayed with me most is the question of whether photography can be more than a voyeuristic enforcement of sight, more than a one-directional action.

Walking around the Saatchi Gallery on that evening I thought, yes, clearly, it can be. JR’s photos don’t take agency away, they return it; they don’t superimpose the photographer’s identity, they amplify the sitter’s voice. I’ve purposefully refrained from using the word ‘subject’ when referring to the people JR photographs because, although he alone performs the action of taking the photo, I don’t see a passive role in his images. His commitment to the communities he works with pervades the rest of his practice too: from pasting collaboratively to refusing any media attention and corporate sponsorship, he remains intent on letting his works take the lead of the social dialogue.

Only by sitting down to write this, I’ve realised that this year I have seen other photography exhibitions where the images and the artists upheld the same democratising impulse. Zanele Muholi captures the black LGBTQ+ communities of South Africa, focusing their lenses on personal experiences and expression as much as on the social stigmas these groups still face. Lalla Essaydi subverts Orientalist and exoticising visual narratives, exploring notions of cultural identity, diaspora, and transgression in a highly autobiographical tone that still remains incredibly universal.

These artists turn their cameras on communities and social issues that they know, that they have experienced on their own skin, and which they can treat respectfully and represent justly. While JR’s projects span continents and involve diverse groups of people, and while sometimes their XXL formats and visually enticing perspectives take centre stage, their message and practical, immediate results always pivot on the individuals and communities they touch.

—

Manuela Gressani is currently a Master’s Candidate at The Courtauld Institute of Art.

David Driskell: Icons of Nature and History at The Phillips Collection

by Anna Ghadar

I grew up going to the Phillips Collection in Washington, DC with my mom any chance I had. She’d ask me what I “saw” in the dimly lit Rothko room full of the artist’s color studies and I’d usually respond “a sandwich” or “a sunset.” Some of my fondest early memories around viewing art take place in this building.

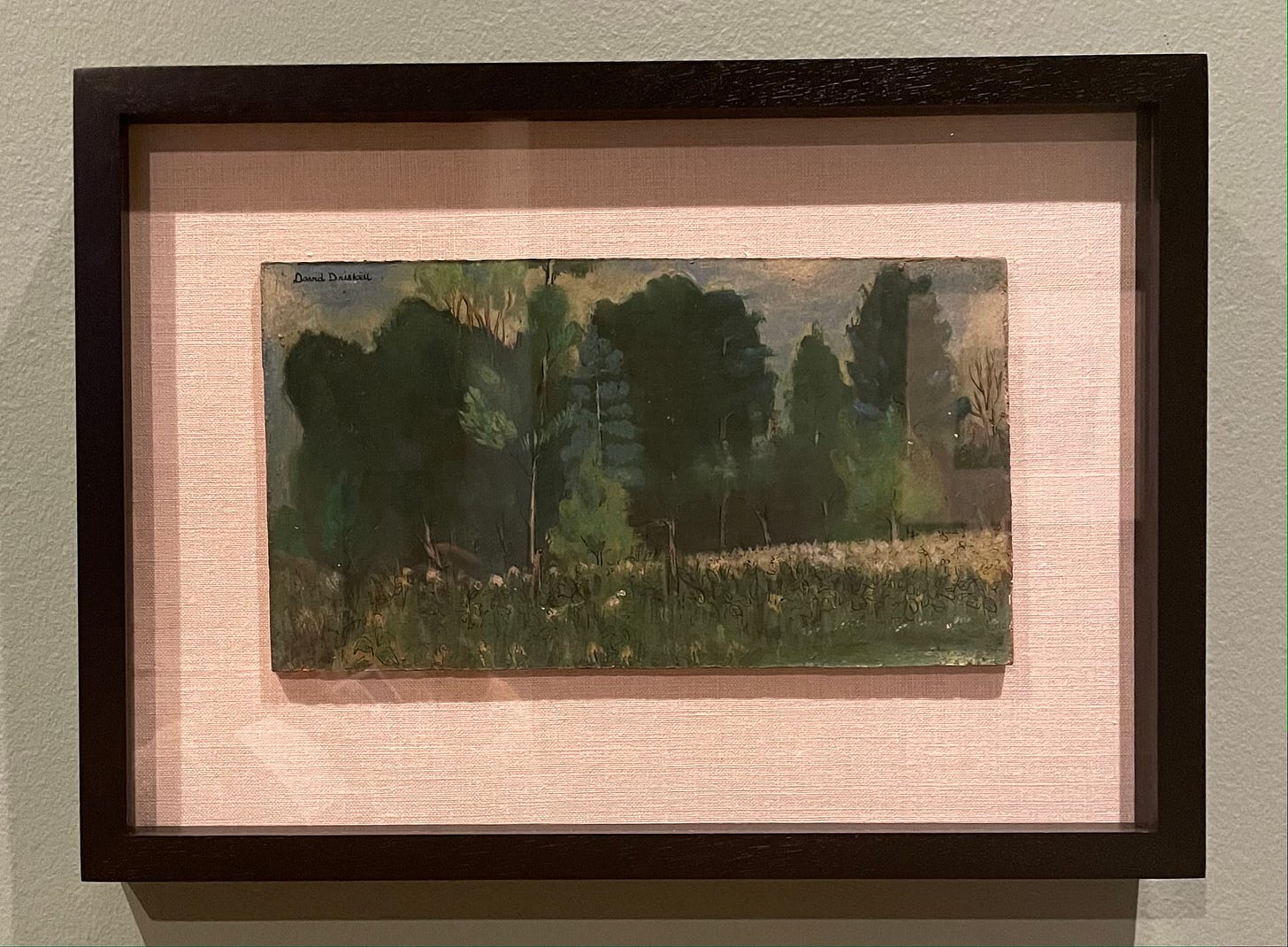

The opportunity to visit David Driskell: Icons of Nature and History at the Phillips adds yet another cherished memory of the space and its programming to my list.

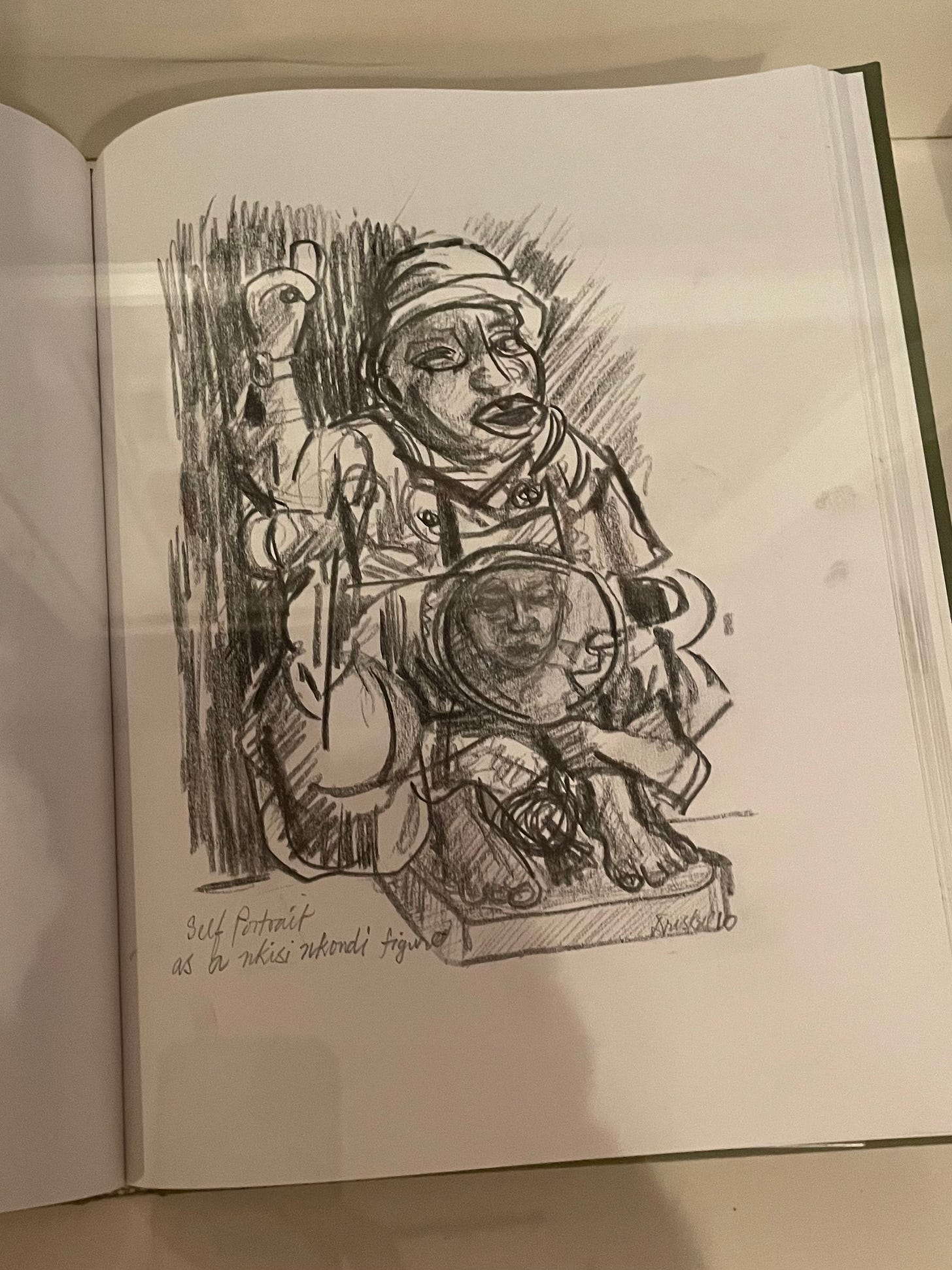

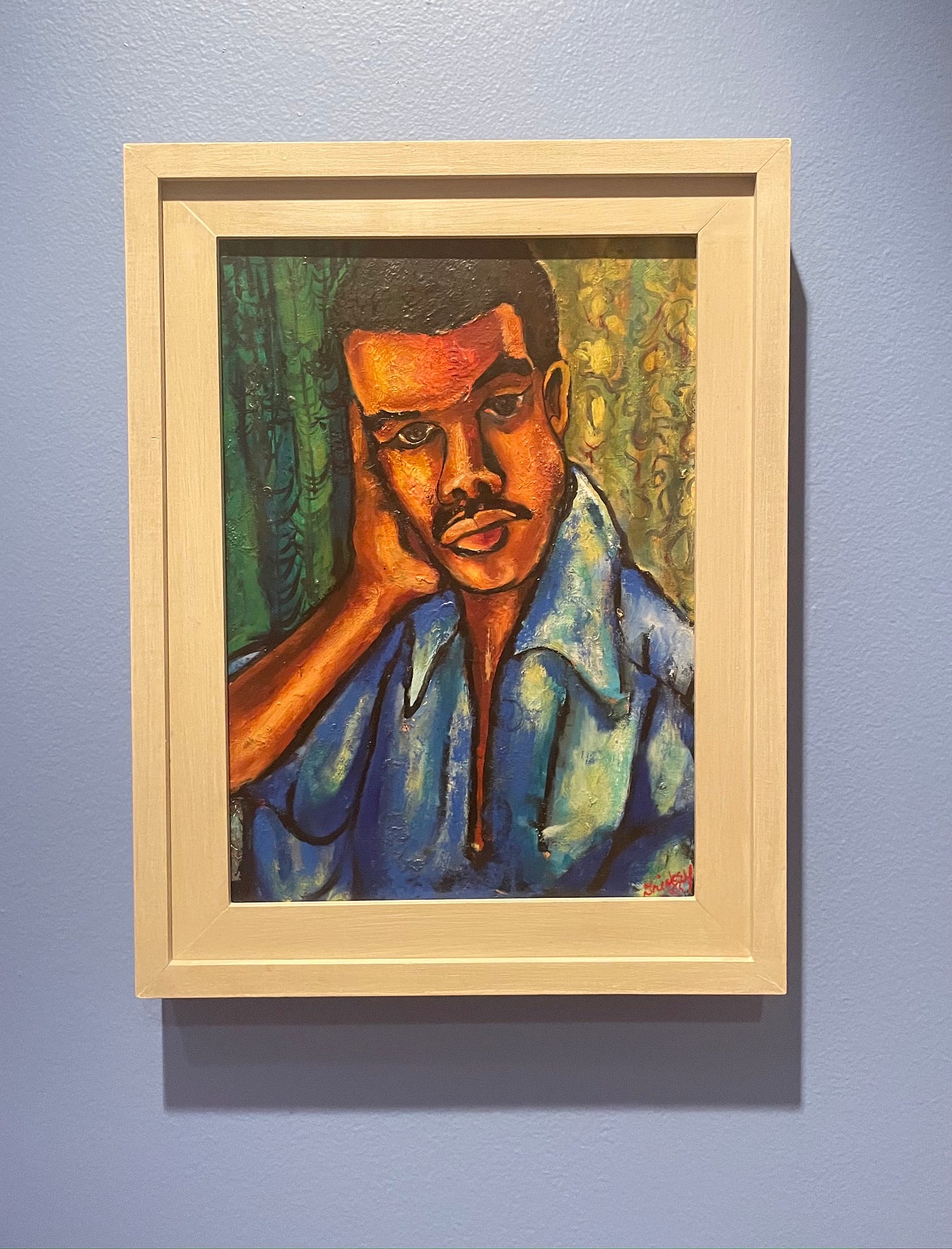

David Driskell (1931-2020) created work that is colorful, textural, and infinitely referential. It’s a real treat to view. The show takes place on the top floor of the main exhibition space at the Phillips, and the show winds you through the start of his practice at Howard University—also located in DC—and winds through meditations on his childhood homes (see the sentimental miniature, My Father’s Farm), sense of self (often through self-portraiture), African Diasporic iconography (such as Nkisi Nkondi, or Kongo “power” figures), and other abstracted figural paintings and collages of historically and emotionally rich topics.

Driskell is arguably one of the most important and influential American art historians of all time. He is lauded for his key role in establishing the field of African American Art (obviously, Black and African American artists were creating long before his time, however, they’d been often overlooked or sidelined). Driskell curated shows featuring now-canonical artists Romare Bearden, Elizabeth Catlett, and Jacob Lawrence.

To me, Driskell is a heavy hitter scholar/curator/art historian. So much so that I didn’t even realize he had a studio practice until I watched the 2021 documentary, Black Art: In the Absence of Light. However, it’s so clear now that his symbiotic relationship with others throughout his art school background and studio practice is what breathed such life into his curatorial and art historical endeavors.

The artist’s attention to how each color, shape, and form in his practice may be perceived speaks directly to his curatorial eye and art-historical approach. Driskell uplifts the imagery he wants others to see and engage with, both in his well-known academic career as well as his equally important studio art career.

—

Anna Ghadar is a writer currently based in Washington, DC. She recently completed her MSt in the History of Art and Visual Culture at the University of Oxford.

Interview with Artist Emma Hambly

by Georgie Byworth-Morgan

I interviewed Emma Hambly via a zoom audio call. Hambly is a multi-media artist whose work is politically motivated and focuses on themes including environmentalism and information transmittance in mass media. We discussed her work, the politics behind it, her use of photography, and her experience of undertaking the MFA at the Ruskin School of Art, which she will complete in summer 2022.

Hi Emma, could you give us a little background info about yourself?

Hi, of course. So I am what I think is referred to as middle-aged. I did a PhD in marine virus biology when I was younger, and was initially a scientist. I worked as a postdoc for a little while, until about 15 years ago when I left science after becoming disenchanted with the field. The reasons for this change still resonate in my current practise. One of my main interests in arts is knowledge and information generation, and the way it is transferred through society. I left science because I felt that it was too partisan; funding is very political and you have to question people’s motivation. However, I’m a hopeless, horrible idealist, and so I found that science didn’t do what I hoped that it would.

How did you transition from science to art? What brought you to the MFA?

I had been doing a little bit of filmmaking with some friends while I was still working in science and I thought it would be interesting to make documentary films. I hoped to communicate what I perceived to be truth to the world. So I went to art college to do a foundation course in the hope of learning something about aesthetics and how to manipulate people with visual imagery. Until that point I hadn’t fully appreciated what art is and what it can do.

I did a BA in painting at Edinburgh College of Art about eleven years ago. Through doing the MFA I hope to fully commit to art. But what’s really brought me here to the MFA is that I’m interested in what art does and can do in a political manner. That’s my underlying reason for being here.

Most of your work is centred around rural and coastal landscapes and natural forms—is the political nature of your work rooted in environmentalism?

Undoubtedly yes. My prior experience and education in science were driven by a love of the natural world and a curiosity regarding how life came to be. I am a deep ecologist in the sense that I am profoundly in the mind that humans are an aspect of the ecology of the world and that we don’t stand outside of that in any way. We are just part of the ‘big soup of everythingness’, you could say. Moreover, part of my disquiet about science is that for quite some time now it has positioned humans as separate from ecology. Although the ecological movement has been active for a long time now, and we have been aware of our impact on the earth for a long time, even now, the institutionalised side of science doesn’t fully engage with that. When thinking about information and how it is transferred in the media—I’m interested in how a normal, rational person can pick out true information from the ocean of provocation, misrepresentation, and lies that we are faced with by today’s media. It’s a huge challenge of our time. And also, another significant area of my interests is linked to how people seek to affect change when the system is trying to prevent them from doing so.

Thinking about the way information is transferred in the media and how the public can effect change seems particularly pertinent in the current moment when the Home Office are bringing forward the Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Bill, which restricts people’s ability to peacefully protest.

Absolutely. I’m concerned about the civil liberties which have been removed from us over the course of the last year in connection with the coronavirus. And now it looks like they will outlaw peaceful protest. State and protest are two interacting things that evolve together. The dissenting organisation seeks to chink the armour of the state. The system evolves such to make those chinks defensible again. It’s an evolving process between despots and people who are seeking to retain human rights. I’m currently focusing on how to visualise these thoughts—how to turn them into something more than thoughts.

You work across various mediums - could you speak about the use of photography in particular in your practise?

Photography is one of the mainstays of my work thus far. I still shoot analogue film because I’m of an age where I always have done and always will. I’m really interested in photography as a medium of idea presentation. Light is of particular interest to me, which is linked to my scientific background. Through photosynthesis, light energy is transformed into biological energy by plants. When I shoot analogue film, the photon of light that is reflected off an object is embedded in the film and that is what makes the image. I’m kind of a purist about that aspect of it.

Going forward, how do you expect photography to function in your work and how is that linked to the politics driving your practise?

As humans, we so viscerally respond to images of other humans, and I think that there is tremendous potency in that. They speak about the role of the individual in society. I was raised as a Quaker, and Quakers are all about equality and recognising that everyone is an individual and is equal. I think that portrait photography will be crucial to my ongoing work - I never cease to be fascinated by individuals.

Politics are also central to my practise. I got involved with local politics some years ago - I stood for county council elections. At the time I definitely felt that that was part of my art as much as any drawing or photograph. So, for me, the whole lot is tied together. Right now, I’m extremely interested in the power of discussion and dissent.

You often photograph using old, expired films - could you talk about the significance of that?

Physicality is central to my work. My dad died about 25 years ago and he used photography for his work as an engineer. He had a stash of film that I acquired some years later which I use. Of course, it has tremendous potency as a medium for me because the film was my Dad’s. Some of the cameras I use were my Mum’s, such as a box Brownie that I make long multiple exposures through. The camera that I took the photographs of the magnolia tree on was my Dad’s. They use straight 35mm black and white expired film. I love those images—for me, they are a reminder that we are from the earth and we are all connected to it. There’s also something about timescale and the brevity of our lives in geological time. I like this counterpoint; it’s simple but profound. I think all art is autobiographical in some form.

How has your experience of the MFA been?

Although I’m quite averse to everything being online, and I initially wanted to defer my place because of that, I’m extremely glad I didn’t. I think the course has been managed amazingly well and that it’s been a fascinating year thus far. There’s a kind of intimacy that’s developed within the cohort which may have not been present under normal circumstances. It’s an amazing cohort and it’s fantastic to be amongst such a bright and interesting group of people. There is a very strong political sense amongst them—it feels like a very dynamic, active, and socially responsible group to me. These people are really paying attention and looking at the world and thinking about how to right some of the wrongs that they see.

Thank you very much.

—

Emma Hambly is a visual artist, see more of her work on her Instagram (@emma_hambly).

Georgie Byworth-Morgan is currently a Photo and Editions Intern at Phillips Auction House. She recently completed her MSt in the History of Art and Visual Culture a the University of Oxford.

Please follow us on Twitter and Instagram (@poltern_) for updates and share our newsletter with anyone who might be interested.