Welcome to the eleventh Poltern Newsletter

This month’s issue includes an introspective selection of poems by Sophia Massidda; a nostalgic piece prompted by the fairytale illustrations of Amanda Blake written by Eva Tain; a ruminative review of Tokyo: Art & Photography at the Ashmolean Museum by Anna Ghadar; an engaging interview with artist Gabriele Uboldi on his recent multimedia work, London/Londra, conducted by Victoria Horrocks

If you have any questions or comments, please do reach out to us by responding to this email or writing us at polternmag@gmail.com.

Thank you for being here.

The Poltern Team

Selected Poems

by Sophia Massidda

—

9/29/21 shards of glass in good machines

behaving badly again

looking down at my feet

light came up

from the floorboards,

underneath

they tore down our old high school

5 years ago, they said

asbestos under every carpet

filling up the woodshop shed

but our lungs still function nicely

shards of glass in good machines

and we washed each other in the river

never again will i feel so clean

never again will i feel so clean

never again will i feel so clean

6/3/21 the tunnels

finding my mind on the tile walls

feeling sick late morning

red candy stripes, outside white sky

swallowing the top

of the prudential

but there’s always dim yellow light in here

and asphalt glittering like the stars

(outside the city, where you can see them)

skyscrape behemoths in the fog

always shit going down in nubian square

every weekend going somewhere

heading back there

falling through the air

dozing in my chair

growing out your hair

every fair from fair

only if you swear-

and back again, in nubian square

still with its cop lights

and its bag ladies

and me

in the tunnels

8/15/20 bible study

oh, eve, think of the calories!

just because the sugar is natural

does not make the fruit less sweet

he won’t love you if you can’t see past your own stomach

there’s better exercise than shaking all those trees

of course the first sin is woman eating

how dare we open our mouths for pleasure (rather than to please)

poor eve, never thought about calories

—

Sophia Massidda is an actor, poet, and singer/songwriter currently based in rural Massachusetts. When not furiously scribbling her thoughts into the Notes app on her phone, she enjoys taking care of her two cats, dog, and beloved horse, Sillygoose. Her debut album, Surrounded by Walls, will be released later this year.

To read more of Sophia’s poems, you can follow her on her poetry and personal Instagrams.

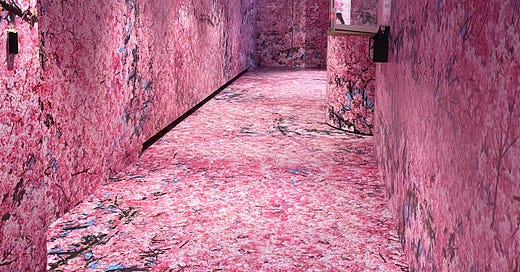

Review of Tokyo: Art & Photography at the Ashmolean

by Anna Ghadar

Tokyo: Art & Photography at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford spans from the Edo period to contemporary Tokyo and attempts to cover over 400 years of socio-political, technological, environmental, and artistic shifts (among others). This is, obviously, no small task, particularly given that the exhibition is solely housed in the inherently limiting (small, isolated, etc.) special exhibits wing.

Thankfully, the exhibition highlights artists’ unique personal and temporal experiences within the capital city. To me, it seemed the goal was not to condense centuries of visual histories into a handful of rooms of exhibition space; rather, it offers rich and deep insight into each particular artist’s lifestyle to cobble together a syndechdical storyboard that alludes to the insurmountable vastness of Tokyo’s history from the past half-millennia. For example, a centuries-old complete set of formal military dress is just a stone’s throw from a compilation of call girl cards from the 80s and 90s collaged into sakura tree landscapes by Aida Makato. Intergenerational artist movements are alluded to through work by the collective Chim Pom hung across from their well known mentor, Murakami Takashi. Modern cityscapes featuring railways, turnstiles, and convenience stores are put in conversation with intricate works on paper detailing and mysticizing the earthquakes and tsunamis that have repeatedly shaken the city’s foundation, visualizing two ways in which the city is constantly, often-times devastatingly, shaped and reshaped over time.

To pivot a bit, I have to say my favorite aspect of the exhibition was the collection of little bobblehead-keychain-figures mounted to walls throughout the show. Just a few inches high, never hung at eye level, always without a wall label. I only recognized these figures by the second or third room. At first, I thought it was a one-off. I couldn’t figure it out—are these little souvenir prototypes from this year’s summer Olympics? Children’s toys? Well preserved collectibles from decades ago? I started taking photos of the little cute things. How many had I missed before I realized they were there? The exhibit was surprisingly thorough for how condensed it had to be given the limited space it had in the museum. However, what I left thinking about were these little anthropomorphized animals. What are they?

Although I have no definitive answer, I like to think it’s an homage to the rich material culture of Tokyo that is inherently linked to that of the visual nature. Oftentimes, Western museums frame Eastern histories through a distinctly colonial lens. Elements of visual and material culture are labeled “ephemera,” given anthropological analysis, and ultimately denied a formal one despite their being in a fine art museum. Some elements of this process can be seen at the Ashmolean’s own ‘West meets East’ room—I feel I need not elaborate on this.

These little easter eggs throughout Tokyo add a playful, exciting element to the viewing process. Each is unique and detailed. They encourage critical engagement sans wall text (as someone always looking for vinyl to make sense of what I’ve seen, this was at first frustrating, then refreshing). They reject linear time and break up any rigidity of theme within each room in the exhibition. Ultimately, they reject the viewer’s desire to consume a neat little blurb on them. There is no condensed story of each figure’s place in time and space—they are a product of the world around them, of the unique experiences portrayed through every individual work on view and the endless others they are interconnected with.

—

Anna Ghadar is a writer currently based in Washington, DC. She recently completed her MSt in History of Art and Visual Culture at the University of Oxford.

Amanda Blake and the Duality of Childhood

by Eva Tain

This morning, while sipping a cup of tea in my childhood bedroom, I absentmindedly scrolled through my art-dominated Instagram feed like the stereotypical Gen Z art historian I am. Rapidly skipping through paintings by Monet and Van Gogh and the occasional ad, I stopped my scrolling to contemplate a painting of a peculiar girl in a pink ballet tutu. She was painted in a childish way, with arms crossed stiffly over her stomach and legs that were too long for her body. Her tutu was too big and too pink, and it clashed with the darker colors of the background. Something about her round face and puzzling demeanor was both familiar and disturbing, which piqued my curiosity.

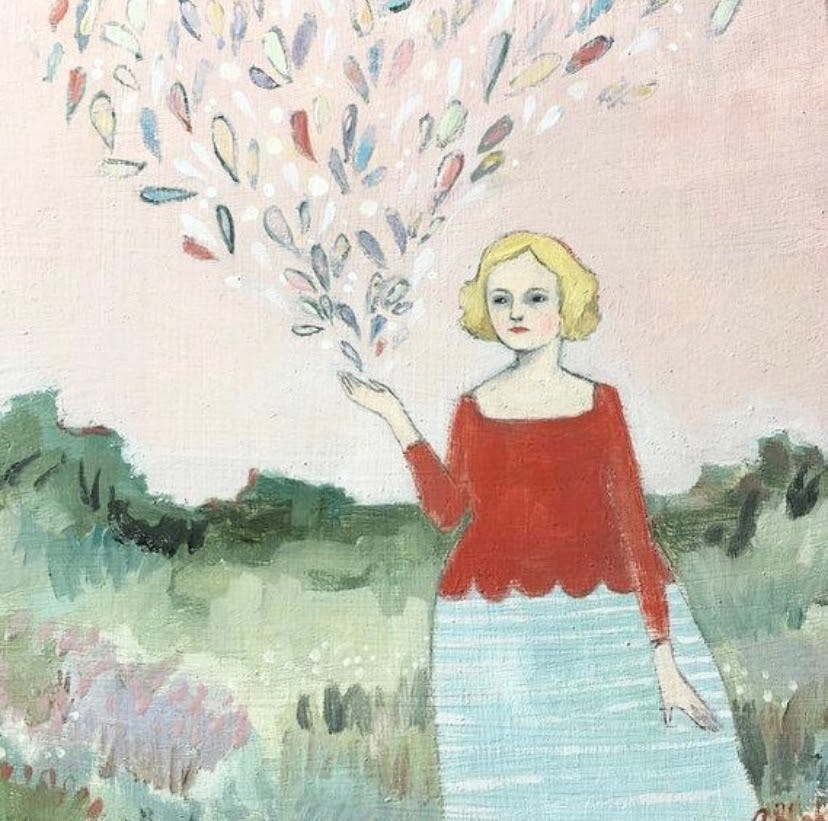

Artist Amanda Blake paints doll-like girls wearing puffy dresses, standing in fields of flowers under skies full of stars. Her childish lines and use of colors echo the almost naive cheerfulness of her characters and patterns. “Oil paintings about hope and light, wildflowers and stars, love and fire,” Blake’s Instagram bio reads, which summarizes her art well.

Originally from Oregon, Blake currently lives in Madison, Wisconsin. According to her bio, she “received her BA in fine arts from the University of Oregon, studied watercolor in Siena, Italy and oil painting and print making at the Chautauqua Art Institute in New York.”[1] Coming from a family of ceramics artists, Blake explained that she “grew up surrounded by art and knew that it was what [she] wanted to do from a very early age.”[2] I was struck by this sense of knowing she harbored about her future, which she seemed to sustain throughout her life. Today, she sells her art online and keeps an Instagram account where she frequently posts about her paintings. It seems, to me, that this prescient understanding fuels her portrayal of childhood.

Blake is fascinated by the hopefulness of being a child. “She wore wings of daydream,” the artist captions a painting that depicts a little girl wearing a pair of sparkly fairy wings. I found myself smiling at the candor and touching cheesiness of her painting and words. Blake paints the world through the eyes of a child to appeal to the child in us. As someone who recently turned twenty-one – which marked the moment I started considering myself a true adult – her artworks that celebrate childhood particularly speak to me.

This specific work of a fairy-winged child fills me with bittersweet nostalgia. Sweet, because the scene depicted is familiar to me: I, too, used to dress like a fairy as a child. I would put on my Tinkerbell outfit every weekend and happily shake my plastic wand around. Bitter, on the other hand, because I no longer have my “wings of daydream.” I no longer find the same magic in life or dream like I did when I was little.

Losing our fairy wings seems to be an inevitable consequence of growing up, which Blake points out in her painting of a blonde woman releasing colorful droplets in the air. Her prominent hips, the presence of breasts, and her more mature clothes indicate that she has reached adulthood. She bears a serious expression as she “surrend[ers] her dreams to the sky,” as Blake writes in the title – the rainbow-colored droplets running toward the sky representing these dreams.

Having reached a certain age, I relate to having to let go of some childhood dreams —to accept that I didn’t do the things I thought I would do and haven’t yet become the person I hoped I would be. As an adult, I feel I have stopped dreaming and have started setting goals instead – realistic ones. Blake’s She surrendered her dreams to the sky depicts this disillusioning stage of life, but turns it into something simultaneously reassuring. I feel a bit better believing that I didn’t give up on my childhood dreams, but instead set them free—that they weren’t destroyed, but released somewhere in the sky. I imagine that, when I’m feeling down, I can look up at the Universe and watch my former dreams dance cheekily with the clouds and the stars, knowing that they are —that I am?—right where they are meant to be.

The question of finding our place in the Universe, and the existential dread that comes with it, haunts Blake’s art, which is why something heavier transpires from her portraits of children. There is something quite sinister, for example, in The stars called her name, which depicts a girl in a purple dress levitating in the night. Behind her, the full moon, placed above her head as if it was her own kind of halo, shines bright. Despite its angelic association, her dead-looking eyes and her rigid position present her as if she is under the influence of some threatening spell, ready to succumb to darkness. By twisting the traditional association of virtue to childhood, Blake reminds us that naivety and angst, innocence and wickedness, light and darkness can coexist.

Blake reveals that she “work[s] to achieve a balance of familiar/other-worldly, pretty/dark […] in order to create an image that people will both relate and want to know more about,” and that “this pretty darkness is the stuff of fairytales and childhood.”[3] Blake’s characters remind me of the ones I saw in Yann and Edith’s children’s graphic novel adaptation of Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights. There is a similar tension between light and darkness in Edith’s illustrations, which had to appeal to children, all while carrying the gruesomeness and maturity of Brontë’s story. While Edith’s drawings were childish, the characters constantly wear unsettling expressions and are surrounded by dark color schemes that made me shiver as a child. Despite its youthful presentation, I recall feeling something eerie and unnerving, perhaps evocative of that same darkness that Blake pinpoints in her own work.

Childhood, according to Blake, holds more than mere innocence and joy. Children play dress up at birthday parties and adorn imaginative fairy wings, but they also anxiously wonder about the meaning of things, existing occasionally in that “pretty darkness.” They reflect our hopes and our fears, as well as the person we were and the person we are. As Blake suggests, children embody a future-oriented wonder that, when we come to inhabit it, sometimes remains as dark and clueless as it was to us when we were children ourselves. Still, that aspirational quality lends itself a vitality.

The children in Blake’s paintings seem to experience both the animated presentness of childhood, one full of possibility and infinite paths to carve, as well as a dark unknowingness of what shape those paths will take. Despite adulthood’s suggestion that we might be able to see clearly the way that once imagined future has unfolded, in reality, I still relate to Blake’s fraught depiction of children. In one of her paintings, Blake draws a little brunette girl surrounded by the lunar phases, who stands in harmony with the world and herself. As I read the caption, Marion found her place in the Universe, I thought to myself: good for you, I hope I get there.

[1] “Amanda Blake,” Sebastian Foster https://sebastianfoster.com/artists/amanda-blake, accessed 27/08/21.

[2] Interview with Amanda Blake, Buy Some Damn Art https://www.buysomedamnart.com/pages/amanda-blake accessed 27/08/21.

[3] Interview with Amanda Blake

—

To view more of Amanda’s work, please visit her website and Instagram.

Eva Tain is an MSc Candidate at the London School of Economics and Political Science. She can be reached at e.a.tain@lse.ac.uk

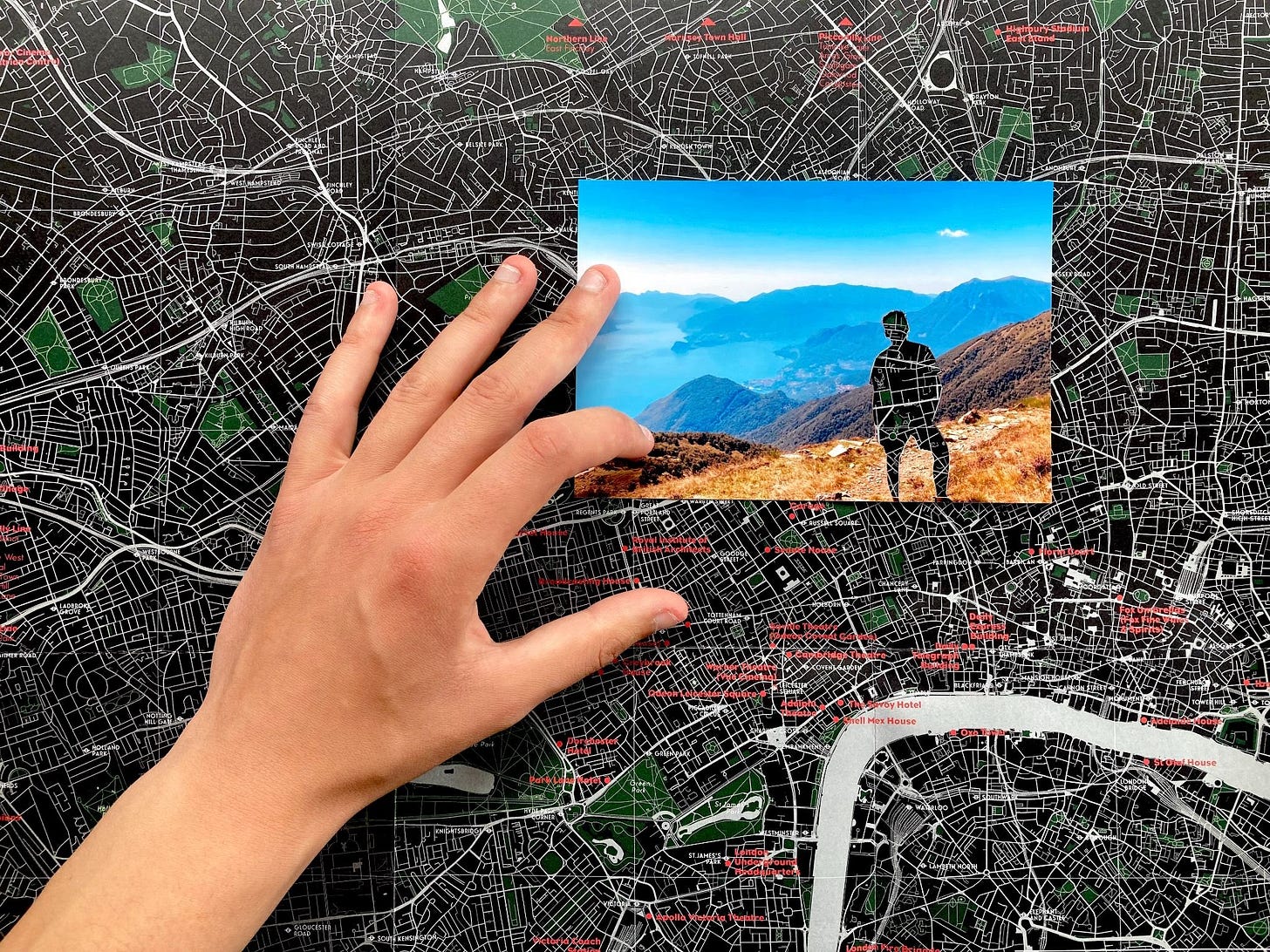

A Conversation with Gabriele Uboldi on London/Londra

by Victoria Horrocks

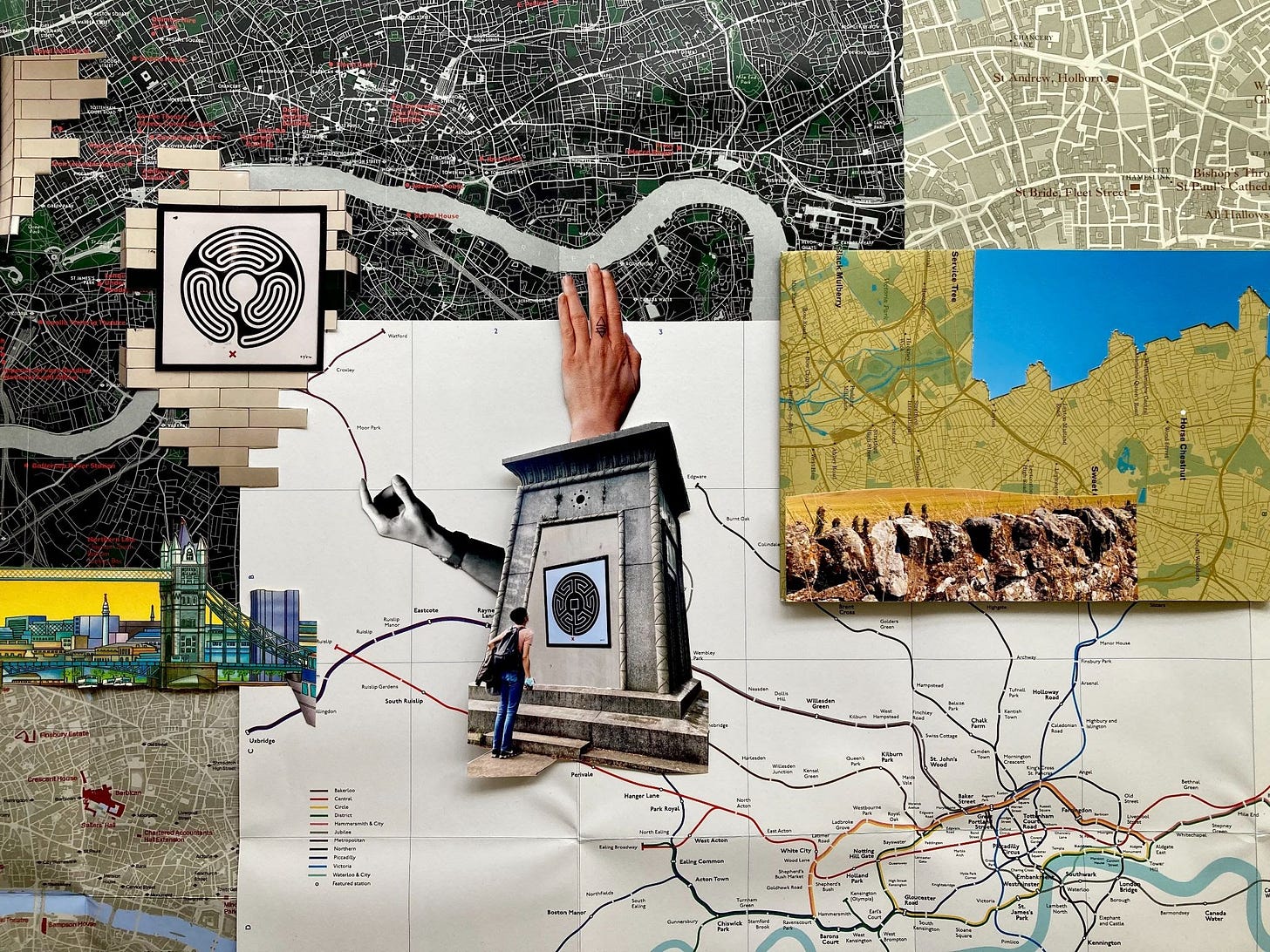

One morning EST, one afternoon GMT, I sat down with artist Gabriele Uboldi to chat over Zoom about his recent project London/Londra, an embodied history-telling piece consisting of three site visits in London accompanied by audio recordings by Uboldi himself. According to the project’s online platform, ‘following the steps of controversial Italian activist Mario Mieli, queer artist Gabriele Uboldi embarks on a digital and site-specific journey to 1970s LGBTQ+ London. Reflecting on Mieli’s heritage and his own queer migration, Uboldi unearths the hidden sites of a history that is both personal and political, exploring notions of queerness and belonging’.

Intrigued by its innovative, digital form, I began our conversation by asking about its method and structure. Soon enough, however, Uboldi and I launched into an exciting conversation about nonlinear narratives, queer history, and the natures of storytelling. We ended thoughtfully on the question of how we conceive of ourselves and spaces through other people.

—

VH: Let’s start by talking a little bit about your method for the project. What inspired you to tell history this way, your history this way?

GU: I think it all started because I moved to London. I think I always knew I was going to move to London at some point in my life, because of certain past trajectories. For example, my mother lived in the UK for a bit, and when I was finally able to I was very excited about it. And so I started thinking about the city itself and what it meant that I was there and where I could go from here. That’s how it started. At first, the project was going to be very personal—I was just investigating my relationship with London and the relationship my Mum had with London, and I just kind of wanted to make sense of it and go back to certain spaces from my personal history. The very core of the project was very simple: I’m going back to the places I’d visited and taking that moment to acknowledge the change that has happened in the meantime, and look at my relationship to the city and with myself and my family, that kind of stuff. But then I started doing some research about people who had done work that intersected with this, and I found out about this guy, Mario Mieli. I’m going to refer to him as he/him, and “guy”, although I think that potentially these days he would be non-binary or gender-fluid, you could say, because in his autobiographical work he refers to himself as he/him and other times as she/her. Anyway, I learned about him and found these insane coincidences between him and myself, and I just had to do something about it.

Mieli moved to London at 19, was queer, and grew up so close to where I did, near Lake Como—literally just a ten-minute drive away. I had only occasionally heard his name when I was growing up: there’s an LGBTQ+ association in Italy that is quite famous that is named after him, but I had no clue as to who he was or what the association did. And again, because of all these coincidences, I could not believe that I had never really learned of this person. So much of the queer history I have been exposed to has been kind of US-centred or, at least from my perspective, British-centred, and I didn’t know much about Italian queer history. Growing up, Italy just wasn’t the place to be queer. This is why I talk about the pressure of just having to move away. I kind of knew that was one of the main reasons why I left, but I didn’t admit it to myself until much later on, like maybe in the past year or so. I had to admit that to myself—that you know, I knew I wasn’t going to be happy there. Now, I am happier for sure. So yeah, to me, queerness had always been embedded in visions of elsewheres, really. And obviously, London was a close enough elsewhere. That’s why London always appeared to me as a queer city. It was always the place to be.

VH: Going back to your point of reading about this figure and deeply connecting with him, it can be so powerful to self-identify with other people to be able to say, oh, I don’t have to be so lonely in my experience. This is something that other people have shared. And I think your project does some of that too. To me, it’s this attempt at a sort of radical empathy. Here you are being so generous in sharing your history and your experience, but also asking the listener to join in, saying we will create your own history too. I want you to share your own histories, as I am sharing my own histories. I think that the project does an exciting balance of sharing individual experience while also welcoming one into a collective. Does that make sense?

GU: It completely does and I’m so glad it came across that way because one of my main concerns as I was trying to find a form for the project and topics to talk about was really like—why should anyone care? You know, this is my story, and maybe people can resonate with it, but I just wasn’t sure. And so, in a way, part of the idea behind the making of London/Londra is to connect my own story to a wider queer history and histories of migration, for example through the figure of Mario Mieli. In this way, my project grapples with something that is objectively interesting within queer history, but I’m also talking about it from my own perspective. And this is something I maybe don’t talk about in the project itself so much, but is an aspect of it I reflect on now: I’ve been talking about a lot the idea—and this is what I really like about queer history as well—that it is important that we find new and different ways of telling these kinds of histories. I think there is something about, for example, I’m going to call it ‘straight history’ or ‘mainstream history’ that is just out there. There is something ‘objective’ about it. You go to a museum and it’s like, this is what happened. And that’s it. And you can go on to do a critique of that coming from different perspectives, like a postcolonial critique or a queer critique, or another spin on that, sure. But one of my main concerns was: how do I tell this story in a way that does not replicate that model of history? To me, it was fundamental to share not only what happened, or this is the story of this person, but something that was more about my own journey of finding out about these things and what that meant to me.

I think, by introducing that kind of subjective look, the point was for me to find parts of my identity and history that I share with Mario Mieli. To me, this becomes a more interesting way and a potentially more ethical way of talking about these things, you know? Because again, Mario Mieli is a figure in this project—and he’s dead—so there’s nothing he can say about that. And equally, there are people that I interviewed that knew him or have written about him, and my concern as well was: how do I tell these stories in a way that I can do justice to them, but also in a way where I am not appropriating them or misconstruing them? My undergrad at St Andrews was social anthropology, so I’ve wondered a lot about the anthropology of art and the relation to aesthetics and the ethics of that. How do you make a project like this? Are you exploiting your informants, etc.? So all of this is at play. And to me, that was a major concern of mine: how can I tell these stories in a way that doesn’t distort or misrepresent these people?

When I finished the final project, I ended up emailing it to the people I interviewed. I was very nervous about it, because they’d been so nice to give up an hour of their time to talk to me about their pasts. And what if they absolutely hate it? Or what if they think it’s this horrible story…like, please take me out of the project, all this kind of stress. But I have had such enthusiastic responses to it. Obviously, I do hope that they liked the project, but I think there is another side to this which is: I think they are excited someone is interested in this. I think that that personal level of this is my journey and I want to tell this story, and also, I want you to help me tell this story, resonated with them.

VH: Yeah, you said in one of the recordings that ‘all history is personal’, and I think that that is such a useful point of entry into telling stories. I think we are taught now in a very positive way to always speak from the ‘I’ perspective, and that’s a sort of new, thoughtful tool for sharing experience and communicating. But I think that it’s also really useful to take that into the vein of history and academia, because you’re so right when you talk about that experience of going into a museum and being presented with a sort of monolithic narrative: this is what happened, this is the objective history, and this is what we are all going to learn. But instead, to sort of take this apart and say: I’m going to approach this from how I feel, from what my experience is—and in a way that’s also not suggesting that that is the new one model of history—it’s opening the door to saying there are lots of different histories and lots of different lenses to any experience. The way that you were opening up this journey into your own experience, while also including these other interviews and pieces of research was really exciting in that it suggested: here are the things that really connected with me when I was doing this, and I thought that was a really innovative way to go about telling a history. How did you find who you wanted to include in your own narrative that way? Was it through research? Or were these people in you orbit you’d had good conversations with before?

GU: I think I was quite lucky because there is so much material out there, and yet at the same time there is so little, and sources are hard to find. It can feel overwhelming—and of course, I was a bit overwhelmed when I first started the project—but I had met this activist and queer historian, Dan de la Motte, and I saw he had curated an exhibition called “GLF at 50: The Art of Protest”. I remember thinking you are exactly the kind of person I should be talking to because it’s still really hard to find information about this stuff. People say this all the time about queer history being erased, or queer history being on the margins, and theoretically, I knew that. But when it came to me having to find the material about Mario Mieli and anything that happened to him with the GLF, it was a bit like, where do I start. I was lucky enough that Dan agreed to meet me.

So, I met up with him at the very start of the project, and he was so nice and put me in touch with a few people who knew Mario Mieli or people that have had a certain role in the Gay Liberation Front and have since been talking about it in an official way. I also knew that Mario Mieli had written this book—it’s an amazing book, by the way: Elements of a Homosexual Critique—that then sort of disappeared from the queer theory canon. What I loved about Mieli’s book was how focused it was on sex and the centrality of sex in queerness, which I think people often forget. That was how the sexual liberation and gay liberation movements were born, right? It was so inspiring to look at these things because it still feels so radical fifty years on. But at the same time, it shows the unexpected trajectories of queer thought—how, for example, from the centrality of sex in the 1970s you then have the AIDS crisis, where obviously sex became a kind of taboo. And the revolutionary fervour of the 1970s also had to be channelled to talk to—rather than overthrow—straight institutions because so many in the community were literally dying. So, to see the ways queerness and talking about queerness had changed was really interesting. To go back to these people who were doing demonstrations in Trafalgar Square back in the 70s and lived in communes and squatted in buildings...

VH: This makes me think of another thing you said, which is ‘can all these Londons coincide?’ Which again emphasizes the individual experience of these people, but also suggests that this meaning-making can come from different times and different versions of that urban space. This remaking of the past recognises the sort of generational inheritance of stories from your communities so that, as contemporary people walking about these cities, carrying with us those histories, we can channel them in powerful ways. You can go through certain spaces and say that history once existed here, and one can connect to that, but one also has a present day understanding of it. Leaning again into subjectivity, it doesn’t mean that there is one linear history or series of events, but instead that all of these different stories are coinciding and happening all at once, and I think that that approach is to history is made visible in your work.

GU: Thank you, I really appreciate it. It’s great to hear a lot of these things because obviously, these are things I was trying to get across. I think it’s right that you brought it back to the city because to me that was always the core of the project. It’s almost become such a baseline that I can forget about it, but it really is about the project’s locations and how queerness and migration intersect and interact with these public spaces. Obviously, Trafalgar Square is a big one, and there’s so much meaning attached to it. All Saints Church is very niche, so when you go there you have to look for hidden histories a bit more. But the site I was most impressed with was Fulham Town Hall. I think it was my favourite site out of the three of them, because of how well it embodies the idea of absences and erasures—this space is out here, but few know about its queer past. I was very lucky as well that it just happened to be open this year for that one month window when I was able to visit it. I experienced that atmosphere of a building that is decaying and is about to be rebuilt…you could sense these hauntings or these secret histories that have happened there. I really felt like I was following the traces of people like Mario, whose journeys have been similar to my own, traveling there. The notion of the city was definitely at the centre of that.

VH: You used such a compelling balance of queer history with the testimony of people who had been there, using archival, primary, and secondary sources, all peppered into your own experience and your mother’s experience, too. What it all really communicated to me was the possibility of a multivalent understanding of a place and the reality that a multitude of experiences can exist even within one singular person. I found it really exciting to be in your head and have you in my ears as I listened to the recordings for that reason. It felt like I was literally in your mind while you were literally in mine, which, again, seemed like a radical attempt at empathy, you know? You managed to tangibly manifest this notion of: you can literally walk in my shoes and you can literally hear the thoughts or voices inside my head.

GU: Yeah, I talk about the heterotopic nature of public spaces—and I’ll talk about it in academic terminology—but again it’s the acknowledgment that all of these things happened in these places, and, in the context of official histories, you have plaques, and museums, and monuments, but then in other instances, and especially when it comes to marginalised histories, it’s important to question how these histories are remembered. This is what really struck me about being able to talk to those people that were there in the 1970s with the GLF: the process of remembering took place through our own bodies as opposed to via a narrative in a museum or a plaque in a certain place or whatever. It is a different, embodied way of remembering history. I felt the pressure of this, of taking on this challenge, when I was interviewing these people, and I want people to experience that as well. I’ve gathered this knowledge and I’m passing it on to you, body to body, and that’s why—you talk about ‘empathy’—but I think I framed it more in the sense of the intimacy of that encounter. Being there, listening, that’s what was important for me.

VH: What do you think is the importance of physically being there in these spaces? The project is constructed so that you can listen to the recordings on your way there, and then you can stand or walk around the physical space, with you almost as an audio guide. I know that you encouraged people on the website to go in person, but of course, I am on the other side of the Atlantic, listening from my bedroom in New York. As a result, my experience going through the project throughout the audio recordings was purely based in memory and imagination, and conjuring. Although I’ve lived in London for brief periods of time, I’ve been to places like Trafalgar Square, but I haven’t been to Fulham Town Hall or All Saints Church. So, some of my audio experience was just pure imagination spurred by the photos you provided on the website and your own voice telling your story. I think that’s also maybe a testament to the versatility of the project? Again, leaning on this notion of subjective histories, and a multiplicity of histories—your project proves that some can be tapped into from memory, others through imagination, others through that sort of tangible, physical experience with the place, and others through grappling with the actual, historical archival material. Anyway—I’m going on a tangent—but essentially what do you think changes when you are physically there in person?

GU: I think, you know, on the most basic level, the project is virtual because of lockdown, and to some extent, we have to acknowledge that. But equally, I think the relationship to the sites is perhaps not too different whether you do it digitally or in person because, even when you’re there in person, these sites can be quite disappointing in a way. There’s a certain expectation that, if you go in person, you might see something or feel something you otherwise wouldn’t, but what was important to me is for audiences to see whether or not they can find traces of these events of queer history that actually happened there. I wanted the listener to get there, to that place, and realize the lack of all these histories. Initially, I almost called the project The Invisible City because of the layers of absences, like, shortcomings and forgettings. To me, the main thing about doing the project in person is really the actual journey to get to the sites, which is also why I focus so much on the idea of the emotional journey. Also, I have to acknowledge that this project is complex to experience in person. I’ve been on a couple of audio walks before and I noticed that, usually, you end up walking for ten minutes or so around one part of the city, whereas for London/Londra you’re meant to go to very different locations, and it takes you a while to get from place to place. That’s also important for my project’s nonlinearity—the kind of, how do I get from place to place. How does my experience of the project itself change my understanding of memory and queer history? That was the most interesting part of it: the idea of literally being there and going on a journey and taking some time out to be like, this is what I am doing today, this is what I’m doing right now, I am going to be going from one place to another.

VH: This embodied experience of telling a queer history alongside the embodied experience of moving and migration throughout a city…I think this is something we maybe experienced first-hand in lockdown—the way that thoughts move as we walk through spaces, or the ways that we can process things as we’re moving around, that connection with the body and the physical movement in some space, and how that relates to the recalling of memory or stimulation of imagination We can all recognize the way that scents or smells or touch and things like that can trigger memory, but I think that there’s a whole other aspect of physical movement, like the movement of our bodies, and re-encounters with space that can also work inform memory. In this case, also the telling of embodied history, which I think is really, really cool to have tapped into.

GU: Yes, I think it’s also about the idea of getting to a certain place with the awareness of the journey you’ve been on, with the added knowledge of everything you’ve discovered. To an extent that was my experience with all of the different sites that I’ve chosen, the more interesting one possibly being All Saint’s Church in Notting Hill Gate, which one of my interviewees called ‘the centre of the gay universe’ at the time. And not only that, but it was also the centre of a lot of different migration patterns. You had it all: anti-capitalist movements, communes, squatters who occupied the buildings, as well as the Black, Caribbean community there, and their activism. All of this kind of stuff. So getting there, and seeing all these different places, you recognize, oh, well, that’s that. The idea that all of these movements and communities are interconnected around this one particular place, too, all these different types of activism and all these different causes. It makes sense for all of them to be there. It illuminates the closeness and community that was fostered, as well as the communal struggle towards something. There were also interesting alliances built that you can see from documents, such as the Gay Liberation Manifesto from 1971.

A huge revelation for me was getting to All Saint’s Church and seeing, just straight in a line, Grenfell Tower. You could look at Grenfell and see it as the tragic consequence of unregulated capitalism, the housing crisis in London, and the ways in which all these issues intersect with race, class, and migration, if you look at the communities living there, those who were affected. It’s really just seeing how all these things fifty years on still have that power. It can still make you realize how all these things are connected.

VH: They maintain a kind of presence, I guess.

GU: You say presence, but in my mind I went to, yes the presence, but also the absence. In a lot of cases, it’s not that you can necessarily see something, but that you can see that something’s missing. So in this idea of presence, there’s this play of visibility and invisibility.

VH: That’s really striking. What had brought us here was what you were saying about getting lost in a city. I wrote down a line you used: ‘getting lost becomes a revolutionary act’. You wrote that moving about a space in a non-conventional way was a queer way of moving through the world. I found that really compelling, especially when you mentioned things like Psychogeography, which was another instance of integrating more ‘academic’ terminology with more accessible personal experience. It’s a cool method. How did you arrive at that understanding of getting lost?

GU: The concept of getting lost was really important to me because of this idea of drifting, this idea of the flaneur, of going about places without a destination and just being able to experience the city in a certain way. I think that to an extent this came up because of lockdown and of all these walks we were talking about, and there are two levels to this: on one level, there’s obviously a huge change in the way we are living because of lockdown, and there’s a huge change in terms of how we are living in urban spaces as well. So, it was this idea of how do we engage with urban space during the pandemic, and how does your walk fit in in this new urban space was central. And equally, on another level, it’s this kind of walking or getting lost that gives you the power to imagine what public space could potentially look like in a utopian sense. To me, that’s related to queerness on a metaphorical level. You know, the notion that I lost myself and I found myself again, these phrases we use to talk about ourselves and our identity. I wanted to connect this queering of the city to discussions around reimagining public spaces, whether that’s because of the pandemic, or because of the conversations that were initiated by the Black Lives Matter movement last summer, or because we’re questioning who owns public spaces—I think a similar argument can be built in relation to queerness. The question of where do we find our histories if they are not inscribed in our public spaces connects all these things: lockdown, getting lost metaphorically, and finding queer traces in the city. Getting lost in the city became a way of creating narratives that can then be embodied in the listener, in the person who is getting lost through those other journeys I was talking about as well.

VH: I’m going to pivot a little bit because I want to talk a bit more about your experience telling your personal history and your experience leaning into this narrative of your own identity, partially because my own research interests are focused on identity construction and narratology. It’s what my dissertation was related to. Since doing that project, I’ve been thinking a lot about the kind of muddiness of narrative and the ways this structured concept of a story insists on having a beginning, middle, and end. It’s been jammed into our heads from when we were young, so I think sometimes we force similar structures onto our own lives to the extent that I’ll go back to my own personal history mine it for these traditional points of narrative. It’s at least something I’ve seen in myself. I think this insistence your project has on a nonlinear history raises the legitimate questions of: where is the beginning? Where is the middle? Where is the end? And most importantly, do those things actually exist? Or are they just points of reference that we impose to make sense of things? I suppose my main question here is: how did you navigate those narrative forces, or did you have to navigate them when you looked back to tell your own narrative?

GU: I’ll talk about nonlinearity first because that’s an easy one, and that’s something I’m really interested in. It’s the focus of my theatre company as well, Undone Theatre: nonlinear narratives and experimental storytelling. To me, it’s related to queerness again because, as you said, we get told all the time that there’s a certain narrative structure that needs to be followed. So, the question then becomes, within some kind of hegemonic narrative structure, who is represented? Whose stories are told through those structures, and how do they uphold detrimental structures of power for the stories of marginalised groups? Also, who are they benefitting, and who is benefitting from them? I love it when artists from marginalised backgrounds make a point of subverting this traditional, linear narrative form, which is why I wanted to do the project in this way. I think this is slightly related to the idea of building the authority of the narrator. Again, going back to what we were saying at the start about the museum, you trust it because you understand the narrative that you are presented with, and it’s a monologic, uncontested narrative most of the time. So, what was important to me was presenting the narrative in the project as a contested one. This is my view of it, and to me that was a way of avoiding building that hegemonic authority of trust me because I’m the narrator, you know? And it opened up all these different windows onto different perspectives of what might be the same story.

In terms of building my own personal narrative…I struggle with this a bit because I think to an extent labels are important. As in the case with political action, I wouldn’t be able to call myself queer if I didn’t think queer people had the same rights as straight people, you know. Equally, calling myself ‘migrant’ also took so long because I think there are different ways of migrating, but I also think there was something important in using that label to talk about myself because I don’t think that there is adequate representation for people like myself in the U.K. I was looking at the data and something like 37% of people in London are first-generation migrants. I work in theatre and I’ve never seen another person with an accent like mine on a main stage in the U.K., and yet that’s 37% of the people living in this city. And that’s why I’ve adopted this label for myself. On the other side of that, though, is that I struggle with the idea of calling myself a queer artist and migrant artist, and saying I am creating queer and migrant work because then it becomes part of my identity as an artist. I’m obviously selling myself as an artist, and when I try to get my work in programme or when I write funding applications these are the boxes that I’m ticking. So, there’s an extent to which they are parts of my identity that I actively commodify so that I can work as an artist, right? But it’s something I’m finding really hard because I wish I didn’t have to sell it this way. Like, recently I received an email from an institution interested in my work saying they really didn’t have any queer artists in their programme. And I was like, well, are you reaching out to me because of that? Or is it because you actually think that the work is interesting? So, again, there’s a way of negotiating identity with how it’s commodified in capitalism and all that kind of stuff. I also found it important, though, from the perspective of taking on these labels and using them in a way that is political. It was also retrospectively in talking about myself. Like I said at the start, I was admitting to myself that I have made this journey because I wasn’t happy at home with my queerness and these parts of my identity.

It was really powerful to talk about these things in the project, but also with my mum. That’s another part of it—I’m saying all these things but I haven’t really had a conversation with my mum about leaving Italy because I wasn’t happy at home, which is quite a hard thing to tell your mother. But equally, it is something I’m kind of already talking about in the project. Going back to all the informants and the ethics of that, my mum is the only other person whose real voice I’m actually using in the project other than my own, and she does speak, and she does speak in Italian, and I’m using what she says in order to tell my story. Her English used to be okay, but now it’s not very good. And I’m creating this work with her own perspective in it, but she can’t really access it. What are the ethics of that? Is that a good thing that I’m doing? And then maybe it becomes unethical... but also this is my story that I’m telling, not my mother’s story. That level of claiming these parts of my identity, almost stealing them away ‘unethically’ from people like my parents…

VH: I think you’re right to suggest that, in committing to telling your individual story, other people will always factor into that, particularly our families and friends. It’s an interesting question you raise that I’m grappling with, but I think, too, there is maybe just an inevitability of telling refracted narratives of other people through our own selves. Maybe it’s just kind of endemic in the subjective experience. Things will always be shaped by our own minds, whether that’s through our senses of identity or our experiences in the world, down to what street we grew up on, where we went to school, you know, all these sorts of things that create this amalgamation of prisms that affect the way we see the world. We inevitably carry with us the perspectives of other people, but that question you raise of where the line is between the way that someone else’s perspective bleeds into my own, and if there is a boundary at all…I think that’s really important.

GU: What makes me feel a bit better is that for now the project is free, so I’m not profiting off of anyone’s story. Whether it’s my story or bits of other people’s stories, I’m not making any money off of them. So, if we talk about appropriation and the idea of potentially unethically drawing from other people’s perspectives, I think there is maybe a level of safety to acknowledging that at least I’m not selling them! But, in a way London/Londra is about writing on London. It’s a home-making project, to an extent. But equally it is a migrant home-making project. It kind of ends up rearranging the dynamics of home. It uses the tools of identity construction to go back and see all of those things and actually claim them for myself or use them consciously to tell my own stories as opposed to the way, let’s say, my parents see me or used to see me, or the way people might see me at home.

VH: One of the things I really wrestled with in my research was trying to break down the notion that something being ‘constructed’ might not also mean ‘fabricated’. Looking at the idea of going back and trying to puzzle together identity, we will often suggest that constructing it means that something has been falsified, that we have cobbled some coherent thing together that might not be accurate, according to some objective truth. And I think that I don’t like that notion at all. It’s so easy to say that because this has been ‘tampered with’, now it’s false, and that there is no longer an honesty to it. But I think there is still rawness, and to use your word—intimacy—in bringing someone into your own understanding of yourself. And that was something, for me, I saw at the fore of the identity construction in your work. Does that resonate at all?

GU: Yes, it’s interesting. To answer not what you just asked but to comment on what you just said, I think it’s interesting this relationship you’ve identified between fabrication and truth, and whether construction is fabrication. I take almost the opposite perspective that you have, because, to me, there is some truth to this, but even autobiography or more factual kinds of narratives are still constructions, ultimately. So, instead of claiming truth to the construction, I prefer to accuse truth of being constructed in the first place. As someone who is a theatre major or a writer, it feels like a very powerful move to say I’m going to harness the power of fiction. And if everything is fiction, then using fiction is an extraordinarily powerful tool. By way of dealing with it, I think it’s not necessarily to about saying this is true and this is not true, but rather to say well, I’ve learnt the tools of claiming authority when I’m telling a story, I’ve learnt the tools for deciphering what feels fake and what feels less constructed. If I’m asked these things, I can tell a story that is a construction, just like every other story, but this time it’s a construction that I’m aware of. It’s almost like I’m performing the construction of it. It’s a story that doesn’t hide the extent to which it is constructed.

VH: That’s great. Super interesting! So many thoughts are swirling around my head…

Lastly, is this project something that’s ongoing? Will you continue to add parts to the journey? In the spirit of creating nonlinear narratives, where does this project end?

GU: Yeah, I think I made it with the intention of the three sites for now, and I can always add more if I have something more to say. But I’m also toying with the idea of turning it into a solo show or a theatrical thing, and that’s interesting because it raises these questions of maintaining nonlinearity and how I could continue to focus on the city. What would happen to that idea of embodied memory and the intimacy of it? I’ve also thought about potentially leaving it for another ten years, and then in ten years’ time looking back at it and noting layers of time and identity. Like, wow, look at this person ten years ago making sense of their own story in this particular way. Ten years on, things have changed in this particular way or my identity has changed. These kinds of things…maybe creating a kind of Russian-doll structure for it.

I hope people see the project. I hope people listen to it. I feel like I’m asking a lot of people. Especially if you are there in person, it is quite a big ask, which is something I think could potentially be a problem. But it’s good to hear that you have felt that kind of empathy or intimacy because to me it almost felt like I haven’t defined the audience enough. Part of me wants to rewrite it, as letters to a lover, perhaps, creating a more defined person to tell my story to... but that would be a completely different project, as well.

VH: I loved what you said in the recordings of liking to think of different cities as different men that you’ve met. I thought that was so good. In a figurative way, we can characterize cities as people, but also in a very real way, too, I will always think of certain people when I re-enter the spaces I once shared with them. I think that can be a really different, powerful lens to explore our memories and our histories through other people, especially lovers or partners or friends who, again, have that kind of closeness to us. Anyway, I thought that was a great line.

GU: This is the thing—it’s interesting to think of how people can come to represent places and the other way around. There’s a kind of tension between embodiment of identity and the symbolic representations of all these things we use to make sense of it, all via the space around us.

—

If you’d like to read more about London/Londra, you can see and participate in the project at www.london-londra.com. You can also learn more about the artist, Gabriele Uboldi, and his work from his theatre company’s website: www.undonetheatre.com.

Victoria Horrocks is currently an MA Candidate at Columbia University in New York.

Please follow us on Twitter and Instagram (@poltern_) for updates and share our newsletter with anyone who might be interested.