Welcome to the tenth (!!) Poltern Newsletter

This week’s issue includes a well-timed creative writing piece (+ recipe!) inspired by tomato season, which points to works by Gina Beavers, Mary Ann Currier, and Chloe Wise, among others, by Hannah Kressel; a captivating review of mixed-media works on view at Tomashi Jackson: The Land Claim at the Parrish Art Museum, by Victoria Horrocks; a feature that digs at the darkside of nostalgia, prompted by Australia-based visual artist Sidney Teodoruk’s UK solo-exhibition debut, Pop Nightmare, at D’Stassi Art by Anna Ghadar.

If you have any questions or comments, please do reach out to us by responding to this email or writing us at polternmag@gmail.com.

Thank you for being here.

The Poltern Team

Musings on tomatoes in and as art | Creative Writing

by Hannah Kressel

I sliced my finger cutting a tomato today. This one was golden — low-acid the garden catalog promised to its ulcerated readers — heavy, with taut skin, like a lump in the throat. Different from the mealy cross-section subject of Joe Brainard’s 1975 gouache painting. That tomato was a salmon pink; the tender intimates of an otherwise blushing creature. Nearly translucent membranes cradle a huddle of yellowish ruby seeds.

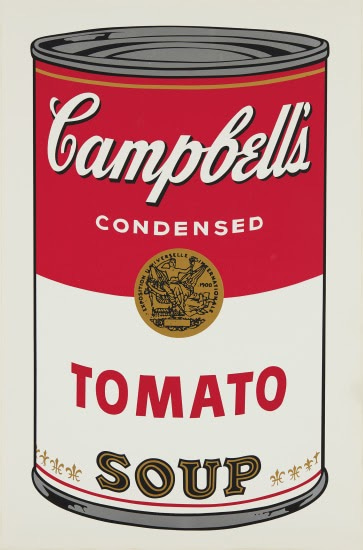

In Mary Ann Currier’s pastel still-life from 1984, the red fruit causes the otherwise serene canvas to ache, disrupting the pacifist colors and lines from which three onions spur. A knife lays before the indignant, rotund tomato. Perhaps this tomato was purchased mere aisles away from tomatoes of another sort. Those pulverized, sweetened, salted, and destined for a tin coffin — the kind made famous by Andy Warhol in 1962. Perhaps Currier’s tomato was pulled from its perch on a wooden display; a display which also housed those like the darling grape tomatoes adorning the wrist, attached to a hand, in Caitlin Craggs’s 2016 stop-motion animation, Tomato.

These tomatoes, the ones threaded on string forming a bracelet in Craggs’ video, would make for prime specimens in Elizabeth David’s recipe for buttered and sauteed tomatoes. Slice the tomatoes in half and nestle them into a medium-high heat bath of butter. It is imperative that one pricks the rotund backs of each tomato half, to maintain the fruit’s integrity. Finish with cream as David suggests, and Rebecca May Johnson reiterates in her own 2019 documentation of the recipe. Johnson writes:

“These dishes strike me as things I would like to cook. The specific timing and proportions – an inch, a half inch, into four, small pricks, cut sides, serve immediately – seem to bring qualitative benefits and drama to eating. I can see why David was so excited. Details like this given in recipes can make me think differently, again and again. Have I thought enough about the potential of things? A heavenly future might reside in a handful of tomatoes if I achieve the requisite intimacy; if I think enough about how they are affected by processes.”

If you are to make them yourself, definitely cook the grape tomatoes (especially if they look like those within the plastic produce bag, weighed on a scale in Jorge Furtado’s 1989 Ilha das Flores). Perhaps you could roast them, for hours, drawn to submission by the dry heat of the oven? Maybe in a pan with a heavy hand of olive oil, until bursting and jammy? Watch the pan and listen to the hisses of steam as the tomatoes shrink against the fire’s unforgiving heat. Once they are sufficiently wrinkled, scoop them into a bowl. Then, without wiping out the pan, throw in a tumble of tender herbs — basil, mint, parsley (ideally something tasting of early evenings in summer) — and a few eggs. Scramble or let set into an omelet. Serve with the jammy tomatoes, perhaps with a drizzle of watered-down tahini, next to a slice of walnut rosemary sourdough. That’s how I cut my finger — nothing to fuss over — slicing thick golden medallions to accompany a slice of walnut and rosemary bread. A recipe I just can’t seem to get right, despite waiting exactly three hours and conducting precisely three turns on my dough as mandated by Maurizio’s recipe.

Incidentally, tomatoes were first offered with fingers. Early Aztecs served the glistening fruits in stews of human flesh to serve their priests. Juicy, red, so often mealy. Nowadays, who can imagine Italian food without tomatoes? Grilled alongside eggplants, sliced among petals of lettuce, or long-simmered with star-shaped sections of okra (consider James Peale’s still-life, c.1820). These tomatoes were quickly plucked, painted, and eaten, one hopes, like apples; so unlike the poor souls destined for Warhol’s Campbell cans, knowing no intimacy.

Tomatoes may also be pickled. Verdant and unripe, they are picked from the vine and sliced into toothsome sections. As in LAZY MOM’s 2018 work for a holiday photo series in Vice, sections may be suspended — either in vinegar with sugar or perhaps resin or jelly or frozen in cubes. There are tomatoes, and there is art. Red, space, lines, and densities.

Perhaps the tomatoes are juicy and dripping down your hand, or dribbling from the corners of your mouth, leaving residue somewhere between water and juice. Like Goya’s Saturn, the red tomatoes were once devoured among flesh. They are now just as well consumed with spaghetti (as in Chloe Wise’s 2016 sculpture featuring the dish) and for their paler cousins, served with griddled meat (as in Beavers’s 2014 painting, Yummm.)

Run to the greenmarket, grocer, or garden — it’s tomato season!

Recipe

Room temperature tomatoes, cherry, or heirloom (truly any variety, but these are my favorites)

A splash of red wine vinegar

A three-finger pinch of sea salt (of any variety, or Diamond Crystal)

Glug of grassy olive oil

Slice tomatoes into palatable chunks. Macerate in oil, vinegar, and salt for 15 minutes. Eat outside at dusk.

—

Hannah Kressel is currently a Candidate for the MSt in History of Art and Visual Culture at the University of Oxford.

Tomashi Jackson: The Land Claim at the Parrish Art Museum | Review

by Victoria Horrocks

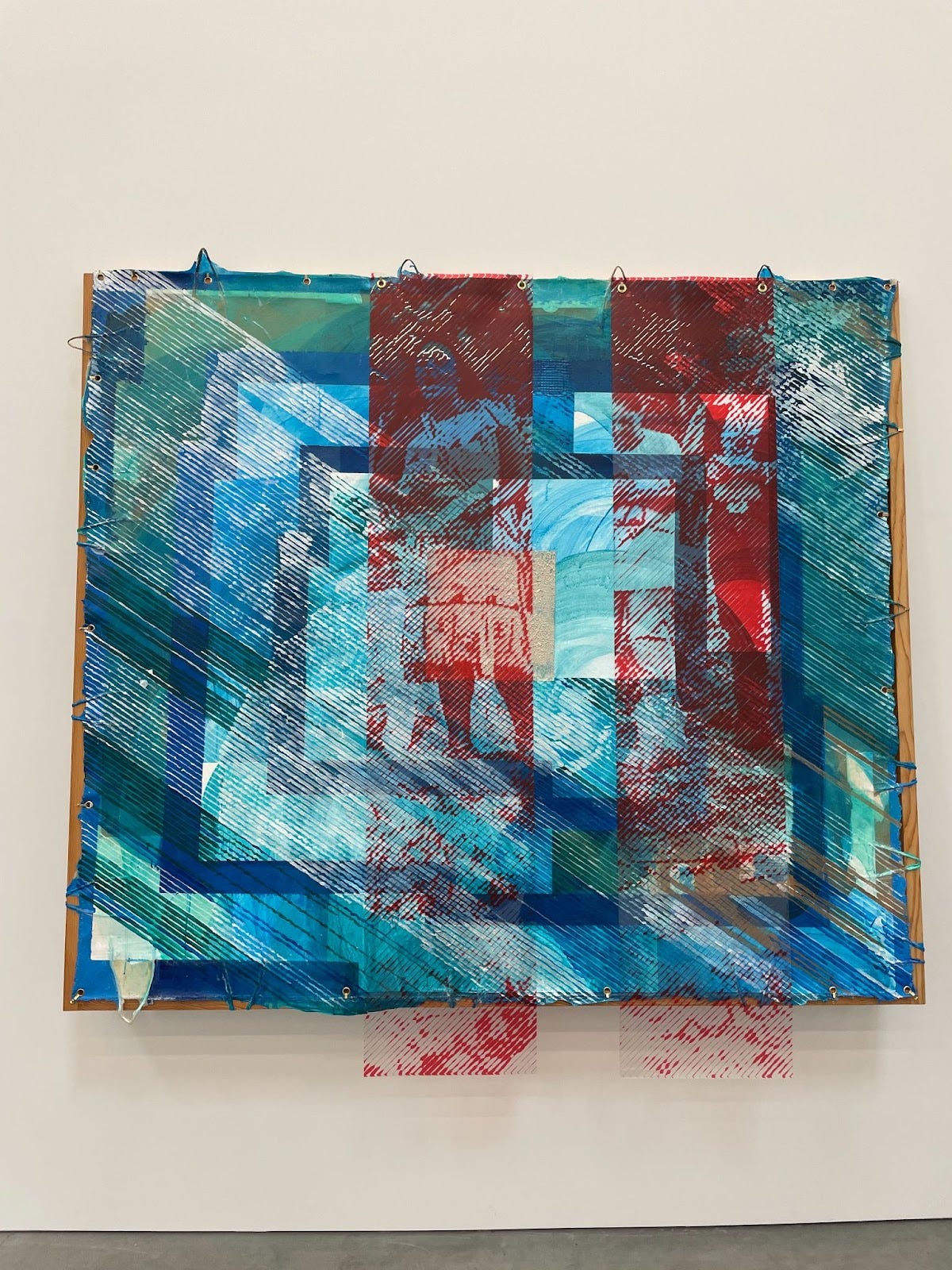

If you walk into the Parrish Art Museum right now, the first work you’ll see is Tomashi Jackson’s 2021 work, The Three Sisters. The painting overlays images of intergenerational groups of women: a tintype of two unnamed Black women from Eastville, Sag Harbor merged with a picture of members of the Hunter-Silva family at “Ma’s House.” The title of the piece nods to the North American Indigenous farming method of planting corn, squash, and beans together—a process by which each crop supports the growth of the other. Through Jackson’s creative and tactical layering of lines and color, she blurs time and collapses histories to emphasize the interconnectedness of local communities. Jackson says of the piece: “They collide, they collapse, like sediments of history.”

The Three Sisters teases the show that unfolds at the opposite end of the museum’s shed-like building. As an exhibition space designed to evoke the “vernacular architecture of sheds and potato barns,” which have historically doubled as workspaces not only for farmers or laborers but also for artists as studios, it seems there is no place more suited to host Jackson’s latest exhibition, The Land Claim.

The Land Claim is a collaborative show dedicated to documenting generational experiences of labor among Shinnecock, Black, and Latinx communities of the East End of Long Island. Jackson began the project by interviewing members of these communities who have faced disenfranchisement due to their race, gender, forced migration, and the appropriation of their land, agriculture, and livelihoods. The rest of the exhibition, from Jackson’s central large-scale paintings to the show’s title, stems from these conversations. The title was inspired by a conversation with Shinnecock Nation member, Kelly Dennis, concerning ongoing disputes over historically Native American land, which now serves as the site of the Shinnecock Hills Golf Club, just five miles from the Parrish Art Museum.

In the words of Corinne Erni, senior curator of ArtsReach and Special Projects at the Parrish, Jackson’s conversations, interviews, and archival research “provoke an urgent discourse around historical narratives of labor, collective memory, educational access, transportation, and land rights experienced by communities of color.” Indeed, Jackson’s multi-media paintings convey, in form and meaning, the present and past experiences of their subjects by recreating images of people in halftone lines, incorporating significant materials into the work itself, and arranging all its constituent parts in a way that challenges linear time and the perpetuation of a singular historical narrative.

Jackson’s pieces show how history has repeated itself in the consistent disenfranchisement of BIPOC communities and the ongoing efforts to interrupt that continual violence. Works like Among Protectors (Hawthorne Road and the Pell Case) exemplify this by representing images from 22 years apart: Doreen Dennis sitting in front of a bulldozer to protect against illegal development on the Shinnecock Neck territory in 1996 and Chenae Bullock singing a song to ask ancestors to protect sacred Shinnecock burial sites in 2018.

Like Jackson’s work at the Whitney Biennial in 2019, in which she merged imagery of Seneca Village with visuals of contemporary reports detailing the seizure of Black-owned properties in gentrified Brooklyn, the pieces included in The Land Claim juxtapose compositions of hand-painted images overlaid with others printed on vinyl. Her works also use materials, such as cotton textiles, potato bags, and soil from the Parrish Art Museum grounds, which was previously a potato field. In the painting Among Sisters and Brothers (Three Families), for example, Jackson paints an image of the Wingfield sisters atop disassembled “Tiger Spud” bags printed with the location “Long Island.”

Jackson’s choice to use locally sourced and abundant materials demonstrates a respect for the land in question. The consideration of environmental stress affirms the exhibition’s messaging, seeing that ecological issues like climate change and environmental destruction often affect communities of color most pressingly. The inclusion of these site-specific materials also provides a kind of visual representation, elevating the land itself as an actor and participant in the works. By making real-life elements of the land—from its soil to its produce—just as visible as the faces of the Black, Latinx, and Shinnecock community members from her interviews and research, Jackson includes the environment itself in the documentation of exploitation central to the exhibition.

As in The Three Sisters, the piece Among Fruits (Big Shame and the Farmer), made of acrylic, Shinnecock wampum dust, and soil from the Parrish Art Museum grounds, uses overlapping media and linear representations of images to elide histories, collapse boundaries, and suggest an interconnectedness between the figures and materials represented. The figures in Among Fruits include a Shinnecock Indian Nation member, Shane Weeks, holding a hen of the woods mushroom harvested on the Shinnecock Reservation, alongside an unnamed Black man working in a South Fork potato field in the 1950s. While juxtaposing two opposite approaches to sourcing food—the unsustainable practice of monocropping and the traditional practice of foraging—the visual means by which Jackson encourages a collapsing of boundaries simultaneously links the labor experiences of the Black, Latinx, and Shinnecock communities.

While it could be said that such an elision of the distinct histories of these communities could overwhelm the unique identity, culture, and trauma each community has faced, Jackson resists such generalizations by focusing on individuals. The Interviews, a multi-channel sound work outdoors at the Museum’s entrance, relays the recorded audio from the interviews to highlight the individuality of each shared testimony. Created in collaboration with Michael J. Schumacher, the sound work concentrates on a single speaker, rejecting any tokenization of their experience, and relaying stories that conjure collective experience.

The exhibition concludes with the Study Room, a gallery-turned-studio in which visitors are immersed in Jackson and her team’s research process. In the room, viewers are encouraged to share their own experiences, family stories, and images relating to local histories. The Study Room not only promotes the participation and elevation of the individual visitors; it also creates a space for these conversations to continue. The participation of visitors suggests that no testimony is too small, and no history needs to remain untold.

The Land Claim is an example of an exhibition that actively attends to the people and histories it centers. The show’s relationship to the exhibition space, its local lens, and its prevailing message of interrelationality and connectedness manifests in the form and method of Jackson’s investigation of micro-histories. Without sacrificing nuance, the show addresses the vastness and multi-dimensional nature of the issues at hand. And, as suggested in its conclusion, the work started by The Land Claim is not nearly over.

—

Victoria Horrocks is currently an MA Candidate at Columbia University in New York.

Questioning Nostalgia in Pop Nightmare | Feature

by Anna Ghadar

Sidney Teodoruk is an Australia-based visual artist who engages playful imagery of Aussie flora and fauna, symbols of Americana, and various modes of transportation fused with truncated words and complimentary color-blocking. The end result is funky, introspective compositions that play with the idea of the passing of time. The artist’s vast swaths of color and phrases clipped at the edge of the canvas encourage viewers to bring their own understanding of these prompts to the work.

The artist’s solo show at D’Stassi in Shoreditch, Pop Nightmare, gives glimmers into Teodoruk’s own psyche and ruminations while prompting dialogue between artist and viewer.

His work is open-ended and, as such, the viewer is forced to intuit something themselves based on his own prompts in the form of dotted signifiers across the canvas. Additionally, his teasing of childhood—which all viewers have inevitably shared in different variations—drives the force of memory and imagination to facilitate this dialogue.

Teodoruk digs at the charade of childhood innocence by posing toys and ‘nostalgic’ objects against other, arguably more difficult or complex, images such as gun-wielding men or looming military presence. This juxtaposition calls to mind, for me, the problematics of nostalgia. In my recent research and writing, I’ve become fixated on artists who broach nostalgia with intent to cling to innocence as a way of leaning into conservativism and resisting progressive societal change. This technique urges critical engagement with sentimentality, which is often used to insulate our memories from harsh realities.

The artist broaches contentious current events and political topics by prompting the viewer to mull over a seemingly simple question: what do these images bring to mind for you? In some pieces, such as Post Nietzsche and Charles Bukowski: On Dying & How to Write, Teodoruk offers religious iconography with incongruent cultural figures (namely, Nietzsche and Bukowski) alongside vast open spaces for the viewer to fill in the blanks—perhaps with their own experiences, memories, and critiques. In other, more sinister pieces, such as The Search Continues and Untouched Fields Left to Sow (Sew?), the artist includes references to complexities of geopolitics, the penal system, and carceral states. What can we make of torturous legacies of militarization and surveillance? How does the hypervisibility of certain institutions, such as organized religion, compare to the intentional concealing of others, as with state-sanctioned violence? The artist urges you to join the discussion and offer your own insights.

This fill-in-the-blanks approach is central to the works on view in Pop Nightmare. Teodoruk’s visual Mad Libs invite the viewer to engage critically with each juxtaposed symbol, rather than lean into nostalgic escapism. As a result, the show is engaging, rejects linear time, and engages the bittersweet aspects of remembrance.

—

To view installation shots for Pop Nightmare, visit D’Stassi’s site. For more of Teodoruk’s work, please visit his website, here.

Anna Ghadar is currently a Candidate for the MSt in History of Art and Visual Culture at the University of Oxford.

Please follow us on Twitter and Instagram (@poltern_) for updates and share our newsletter with anyone who might be interested.