Welcome to the ninth Poltern Newsletter!

This week’s issue includes an introspective piece on self-fashioning and gender in response to Charlie Porter’s What Artists Wear by Victoria Horrocks and an interview with artist Abeer Loan on her embroidery practice, the implications of textile work in Oxford and Islamabad, and the roles of translation and displacement in her work by Hannah Kressel. Issue 009 also features an open question to you, our readers: What should diversity and inclusion look like in the cultural sector? We’ve included some responses on the rectification of exclusionary practices, rejection of tokenisation within the arts, and more.

If you have any questions or comments, please do reach out to us by responding to this email or writing us at polternmag@gmail.com.

Thank you for being here.

The Poltern Team

Exhibition of the Self

by Victoria Horrocks

In September, I spotted a white dress on a rack of a thrift store in East London. The dress was made of a men’s white button-down shirt. It had been split down the seams to its constituent parts and reconstructed in some new form, a garment crossed between an artist’s smock and tunic dress. Instantly, I pictured myself wearing it in summer. I’d be somewhere green maybe, sporting slender white sneakers I didn’t yet own.

I held the dress up to my body before putting it back on the rack. On second thought, it was rather boxy and probably would not suit me. Two weeks later, however, I was still stuck on this dress, wishing I could be wearing it out in the world—to picnics with new friends, on dates, and to get groceries. When a friend of mine snuck back to the rack and bought me the dress, I held it against my body once more and wondered this time who might have worn its original form. Again, the visions were instant—a gawky substitute teacher standing at the front of a rowdy classroom, a shirt-tucked businessman riding the tube, a poshly uniformed schoolboy waiting at the bus stop. Now, this fabric would be something completely different. There was something exciting about the way the garment was determined to change itself, to appropriate some masculinity and assert it newly as feminine.

Reading fashion journalist Charlie Porter’s latest book What Artists Wear, I was prompted to think generously about the “language of clothing,” as he calls it. In an interview on the podcast Talk Art, he discussed the garment as a democratizing piece of art: “we all understand the language of clothing,” he said, “when you walk down the street, you understand someone approaching you just from their clothes. We are all experts in clothes.” It is not novel to think that what we wear intends to say something about us—how we hope to be perceived or what parts of us we want on display. But, in his book, Porter looks specifically at what artists wore, in public, in their studios, and in private. He treats their clothing like an exhibition of the self.

In the book, Porter turns to himself and writes:

I’m a mess. The cream sweater I’m wearing right now has so many stains and I have no memory of what caused them. I’m guessing coffee. There’s a hole in the seam in the armpit that I’ve darned once but the hole won. I’m still wearing the jeans I gardened in three days ago, kneeling on damp soil. They’re in a state. I’ve worn them every day since.

He then reveals that five years ago he donated a white knit by Sibling depicting the Hackney riots of 2011 to the Victoria & Albert Museum in London, only to see when it was first exhibited that there was a prominent egg stain on the front. “This is my way of being,” he writes, “Garments are a testament to what has been done in them.”

I took comfort in this story when I incurred multiple stains on my thrifted white dress. To date, it has traversed sticky subway cars, brushed crusty park benches, and more. There’s a soy sauce stain from a dinner in the East Village, yellowing on the strap from SPF 50, and dirt from the sidewalk where I squatted to see the bottom shelf of a used-book rack.

Porter’s book is concerned both with these types of day-to-day manifestations of routine that imprint on our clothes, as well as what the garments themselves might encode. He reads artists’ clothing choices as signposts of their “intuitive paths.” In other words, Porter looks not only at how specific garments were used by artists, but also at what the material, the patterns, the shapes, and more, might have to say. Clothing can be a work of art in its own right, and it can also stand as a point of access into the artist’s mind.

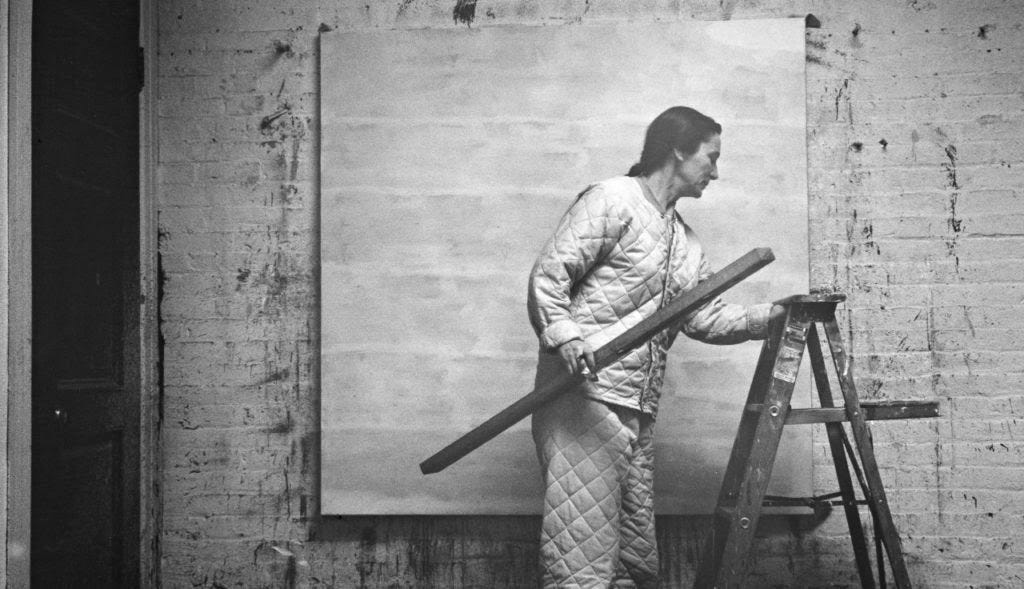

What is significant about Andy Warhol’s Levi’s? What does it mean for him to wear a garment intended to be a factory uniform, the archetypal clothing of the worker? After all, Warhol was so infatuated with jeans that he wore Levi’s underneath his tuxedo on a visit to the White House. And what about the quilted garment Agnes Martin wears in her studio? In the photograph that inspired the whole of Porter’s book, Martin stands in the place where she famously painted her grids, with her hair in a structured braid and wearing a quilted fabric that was similarly linear.

While I was gripped by these questions raised in What Artists Wear, it was a self-portrait of the artist Sarah Lucas which pierced me. One of twelve self-portraits, Self Portrait with Fried Eggs (1996), depicts Lucas seated in an armchair with her legs spread, wearing her own clothes. To the untrained eye, she dons ripped blue jeans, a slate gray T-shirt, and a pair of clunky shoes. There are two fried eggs on her chest.

Porter identifies the crew-neck T-shirt as a kind introduced in the 1930s as an undergarment for male American football players and noted the shoes, known tellingly as “brother creepers,” as having been typical of military men. While her clothes seem traditionally masculine, the two fried eggs on her chest challenge these gendered associations. He adds during his Talk Art interview: “menswear is for all human bodies, but it looks like menswear.”

In Porter’s words, Lucas holds a mirror up to gender, behavior, and identity, and prompts us to consider them all at once by way of clothing. She not only expresses herself in the queering of her clothes, but she also fashions an identity for us, the viewer. As Lucas is known for her feminist artistic practice, how she chooses to dress herself can be considered an extension of her studio work—suggesting that Porter might be right. What artists wear might be able to tell us as much about the person as it does about the person’s larger artistic practice.

In a phone call with Porter, Lucas told him that her clothing stands in for her in some way. She discussed a work made of her own worn-in Doc Martens, to which she affixed razor blades to the toecaps. She gushed over the patriarchy of it all, the gendered toughness she could employ shoes to toy with and expose. Lucas uses clothing as an artistic tool, a vehicle by which to comment on socialized norms and conditioned biases. And she is not alone. In fact, the majority of female-identifying artists that Porter addresses in his book wear typically masculine clothes in a charged act to subvert patriarchy.

The exercise that Porter encourages of his reader in What Artists Wear, one of following the “intuitive paths” of artists and people via their self-selected pieces of clothing, is a caring one. There is a tenderness in attending to something lived, in reading the small emanations by which we create our own definitions and validate our own self-perceptions.

It might be the case that to bear witness to such displays of the self is to listen, not just to others but to ourselves. In these expressions, as Lucas writes, what we wear can stand in for us in some way, if we would like it to. It is no wonder to me now why I adore that white dress: a piece of repurposed cloth, once signaling masculinity and sharpness, that now literally dismantles the fibers of that gendered condition. It says to me that what you were, and what you knew, need not persist. It feminizes that act of taking apart, and of putting back together something which can now take on new meanings. Significantly, these meanings, as Porter says, are “urgent, vital, full of possibility. This is the work we face next.”

—

Victoria Horrocks is currently a Candidate for the MSt in History of Art and Visual Culture at the University of Oxford.

[1] Porter, Charlie. What Artists Wear. London: Penguin Books, 2021.

[2] Diament, Robert and Russel Tovey. Interview with Charlie Porter. Talk Art. Podcast audio. July 22, 2021.

Interview with Abeer Loan, Ruskin MFA Graduate

by Hannah Kressel

A conversational interview between Hannah Kressel (University of Oxford, MSt ’21) and Abeer Loan (University of Oxford, MFA ’21) about Loan’s practice, the differences between working in her native Pakistan and Oxford, and how she hopes viewers engage with her work. Loan works in a variety of media; however, this interview centered on her practice of embroidery on various found objects. Her practice derives from keen observation of the world around her and compromises the division between the public and private sphere.

At the time of the interview, December 17, 2020, Loan was based in Islamabad, and Kressel was in New Jersey. The interview has been edited for space and clarity.

—

HK: Hi, there! Can you hear me?

AL: Yes, I can. Will the interview be more conversational or quite formal?

HK: Definitely conversational.

[Editor’s note: Abeer and I proceeded to chat for ten minutes comparing our Michaelmas Terms. Very conversational!]

HK: Yeah, they’re no longer allowing non-residential students to enter [Wolfson] College.

AL: What a shame.

HK: I'm hoping that by Trinity Term, we can have, like, one ball! I just want to have one Oxford-y thing.

AL: Yeah, [laughs] that’d be nice!

HK: I should probably get to asking you some questions.

AL: Yes [chuckles]!

HK: So, my first question: How did you come to embroidery, and how did you decide to use found objects and acquired materials as surfaces in your work?

AL: I think embroidery in my practice stemmed from limitation. When I was in Pakistan doing my undergraduate degree, I was living with relatives. And, in a setting like that, there's tons of societal baggage, I think. Which gradually interfered with my practice, as well. I don't know if I started doing embroidery as a means to overcome that or as a subtle act of rebellion because there are so many things that bothered me or annoyed me, and I couldn't do much about it because it was the way it was. So, yeah, I think that's how I started because I could always get my material and be at home with people, living there and spending time, and just continue doing my work. Since then, it has been working out okay, so I never really stopped.

HK: What do you mean by societal limitations?

AL: Here [in Pakistan], I think being a girl is like — I mean, it's not problematic — but obviously, it's much easier being a boy in Pakistan because there's so much that you get away with. So, the fact that I was living with relatives ... there's a certain curfew. I mean, obviously, they did not impose those sorts of things on me, but [those expectations] were just there. You knew you had to act a certain way. I wouldn't go out after 10:30 at night, or I would have to spend time with them every day and stuff like that; to be polite at all times.

HK: Right.

AL: So, I think if I was trying [at the time] to be outrageous with my work, I couldn't be like a decent little human being living in their house [chuckles]. So I had to, I think, find a balance between being a decent person living in their house and actually doing my own work. I think embroidery was one of those things that sort of did that job for me. I could do my own work and be there as well.

HK: So because [embroidery] is relatively ... I don't know what the word would be. Not a small act, as you were saying — something that you can do while in the living room or something like that.

AL: Yeah, exactly. Initially, when I started in art, I wanted to paint. I wanted to be a painter. But then, over time I just sort of lost interest. And at one point I started painting nudes and it was, like, a big thing. I had to really hide in my room and do it. And I had to hide my work and hope that no one in the house would see it. I had to be super cautious with it. And living that life was just too troubling for me. And I was like, you know what, I'll try something else and see how it goes. So when I was doing embroidery, even though I might be embroidering silly stuff or writing obscene things, no one would know because they would think, Oh, she’s just embroidering stuff and doing pretty things ... flowers.

HK: Right. Right.

AL: I think in terms of that, it was like a little protest even. On a very personal level.

HK: I was looking through your Instagram and reading your captions, and I noticed you talk about how you'll say something funny in your writing or embroider funny faces. I think in one of them it was a fabric printed with flowers and on it, you made faces from the flowers. You embroidered over it. I thought it was interesting that you applied embroidery to this pretty flowery fabric.

AL: Thanks! I honestly can’t remember!

HK: You have a great art Instagram because you talk about your work in the comments, which I appreciate. And then also you documented a lot of your stuff.

AL: The thing is, I feel like I have to talk about my work because people don't understand what I'm doing, especially here [in Pakistan]. Embroidery is something that is defined as a craft because it is on the clothes; there's so much embroidery. So people say, Isn’t this supposed to go on your clothes and not in your art? Aren’t you going to paint? I think because of that it is hard for me to explain to people what I'm doing. I don't have to, obviously. And then I feel like, at some point, you really do need to tell people what you do when they're asking. When they don't understand what you're doing. So that’s why I write a lot about my work.

HK: Does the conception of embroidery as craft or as women's work extend into Pakistan? In your own experience and in how people react to your work?

AL: Yeah, I mean, I think even more than the West, because people, especially women living in rural areas, are so very much confined to their own little homely spaces — there is a very domestic aspect to their lives. So in terms of that, it is very feminine, very womanly. Where I was in Uni was a different city from my home. Four hours away. So every two weekends or maybe after a month I'd come back home and then obviously still have work to do. So I would be sitting, embroidering on the bus (because, as I said before, it was four hours and I couldn't waste that time on a weekend!) So it's funny because people — women, men — would stare at me weirdly and question. The thing is, the women who now do embroidery here come from a certain class. And you wouldn't expect like a — And I don't want to put a label on myself, I don't want to label classes or anything — but according to the general expectation, a person like me wouldn't be seen doing embroidery on a bus. Generally, embroidery is associated with a certain class here. And by my appearance, I don't fit that class. So I think in terms of that, it was really weird for people to see me do that. That sounds hideous.

HK: I mean, you're not the one who's creating the judgment. You're recognizing what the expectation is. And that relates to one of my questions about your work — do you feel your work is understood differently in Islamabad versus in Oxford? Can you speak to the different expectations of your work in either place?

AL: Oh, it is. I think here, at least, the art versus craft debate or just the fine art versus textile debate is very common and brought up all the time. But, I think that's something that I did not have to defend, at least in Oxford, because everyone was doing all sorts of things. So embroidery wasn't a big deal. Especially because I do embroidery as part of my process. So I always have to justify why I do it. But even then, in Pakistan, there's so much other baggage as well.

I think when you're under an institution, what you're doing is justified, as well. Nobody really questions you unless you start displaying work. That’s when I realized, Oh, wait, I actually have to justify what I'm doing because people don't get it. And even the ones who are supporting me here, they're onto me.

HK: [Chuckles.] Do you think that in your own family and community at home, people started taking your work more seriously when you said you were going to Oxford and when you went to Oxford?

AL: I think at home, although my mom does embroidery — she's been doing it for over 30 years — the way she does it is super different from mine. I embroider text and all sorts of stuff, but then the way she does it is very floral and she does it on clothes and, like, anything she can get her hands on and it is the most beautiful thing ever. But her work is never considered art. But because I say my work is art or because I study art or whatever, it is considered art. Actually, that is one of the things I've been trying to explore now that I'm back home, I mean, I've been wondering, is it just the intention then? Because it literally is the same thing, the same thread, the same needle, but just because I put text and actually try to make some sense out of it and she doesn’t — does that make it art? I don't know.

HK: Like, when does something become viewed as art by the outside world?

AL: I guess, maybe, it just has to be convincing enough. Like, I wonder if one day my mom wakes up and tells me: Oh, this piece of cloth, a tablecloth that I made, that's art. And I wonder if my family will be like okay this is art and not a table runner.

HK: Right. There's this idea that art can be functional, that it can't be both. It either has to sit and just be or it can have a use.

AL: Yeah, that's interesting because I mean, generally I feel like knitting or quilt-making or all those things — they do have a function. So they have some sort of value in terms of where they stand. But then with embroidery, it's just a way of beautifying; beautifying things. I mean, it has no function. And so it's just there to make things pretty. And again, in terms of art, that's not acceptable because art I mean, like pretty art, is just not acceptable anymore.

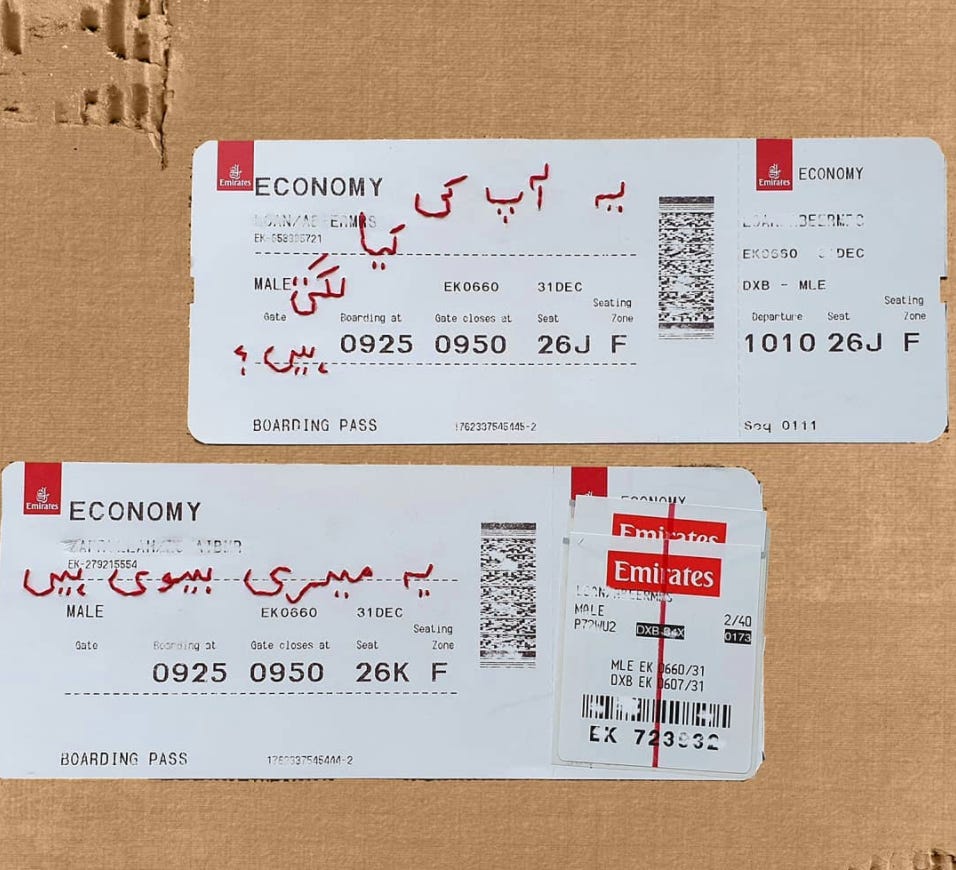

HK: I was curious about the timeline of your work. [On your Instagram] I saw boarding pass stubs and receipts. When does it go from being a piece of paper that you're given, like a receipt or something, into part of your work?

AL: I mean, there's no specific process or timeline. With the boarding passes, of course, I have to wait until I land. The first time I did it, it was just something I overheard at the airport and then it just stuck with me for the longest time and I had the boarding pass, as well. So I embroidered it. But ever since then, I've been very aware, or conscious, of it because there are always things happening and I always try to be more sensitive to my surroundings to actually make or use it as research, really.

Apart from that, I've spent a lot of time on public transport and, oddly, I don't really listen to music. I don't know. I feel weird on the bus or on the train or whatever. But that's a different conversation. But anyway, there are always conversations happening on the busses or the trains. And if you listen to that because people are so loud, it doesn't remain as private anymore, considering I can hear it from like three seats away. So for that, if I hear something on the bus or on the train, I sort of scribble it on my phone. I just write on my notes then whenever I'm home or in my studio, I try to get on with it or sometimes I scribble things down. Later on, I’ll think, like, this wouldn't look too good or doesn't make sense at all or whatever. Other times I’ll hear random stuff and think, yeah, OK, I'm going to use this. For the longest time, I would carry a marker in my purse. When I started doing the receipts I just scribbled them then and there. Obviously, I couldn't sew on a plane. But with the marker, I could always have it with me. Every time I would buy something, I would have the marker and [use it on the receipt.]

HK: Do you find yourself listening out more for conversations now that you’ve started this process?

AL: For sure. I'm definitely more aware. I think it really works in Pakistan because [people speak] so loud and there's always people and conversation. Still, it was very different when I moved to Oxford, because people generally just listen to music on the bus or on the tube or whatever, and I thought, OK, now I don't know how to make work. So there was definitely a disconnect there. And I honestly still don't know how to overcome that. I think now I’m not trying to overcome it. I'm just trying to accept the displacement and working with that. But, yeah, I think the conversation aspect has definitely been reduced now. Also, because most of the conversation we have is online now it is more difficult. When I try to listen out for things, it's more about when people are being spontaneous or saying silly stuff or whatever. Through a screen it's so proper and calculated because I know you're looking at me and you know I'm still constantly staring at you. It makes you aware of yourself as well. So I think that that has been a problem.

HK: So in your recent work, have you been using conversation or are you using different text?

AL: Oddly, I came home a month ago, I had major stuff happening. But anyway, when I was at Oxford, like I said, I couldn't hear anything. So what I started doing, because I felt so lost in terms of my practice and as a new person, as well, in the city, I started sort of embroidering my thoughts, you know, the sort of conversations you have with yourself, like Oh, I don’t know what to do. I'm so lost. I don't know. The inner sort of thing. I started doing that. But then when I came back home, I felt like I was back in my reality.

There's so much happening. I also started doing lots of reading to get my brain going. Also, one of the things I noticed, I couldn't find any material in Oxford. I went to tailors, I went to shops and there was nothing. Like the only thing I found from a tailor was a piece of denim. And I went to this other tailor shop and she was like, “Oh, I only have this curtain, do you want it?” I was like, I don’t know what I'm going to do with a curtain but I guess I’ll have it. I could always go buy thread, but sometimes I don't want to buy things off the shelf because they don't have a narrative to them. They don't have a story to tell. Brand new is hard to work with. It’s like an empty canvas.

HK: Right.

AL: So when I came back home, it was completely different. People were talking at all times. And I've been reading a lot of stuff, as well. The most recent piece of work that I've done is actually a piece of text that I sort of picked up from a book that made sense. But the fact that it was embroidered on a piece of cloth, done in a certain way, added another layer of meaning to it, as well.

HK: So how do you choose your surfaces? Do you keep stuff around, like receipts and things, or do you see something and it just sticks out to you?

AL: Yeah. Yeah. That's literally how I work. Which isn't great. I feel at times — like with this course which is only nine months long — what if something doesn't stick out to me, what am I going to do? I mean I always have thread and basic fabric at home.

At home here, because my mum does so much embroidery and stitching as well, she always has tons of stuff lying around. Every time I have an idea I use her stuff and because there's so much material at home. I don't have to think about it. I can always just use whatever is there. But that was such a problem when I went to Oxford because there was no material, nothing at all. I was like, wait, where do I start with material? So I went around looking for an entire day and I didn't find anything. It threw me off my game because I didn't know what to do. So now when I go back I will be taking tons of things with me because I still need to make work.

HK: Do you think you weren't finding material because there just aren't as many fabric shops in Oxford? I'm curious how the materials connected to Pakistan versus material that you can find in Oxford.

AL: Uh, it's strange. I mean, I went to all the stationery shops and art supply shops, they had all sorts of paint. They had all sorts of brushes and canvases and everything, honestly, that you could need to paint or do the traditional things, which is a really weird thing to say considering there shouldn't be any boundaries in art or whatever crafts and art or all of that sort of B.S. But then again, I couldn't find any decent things for me to embroider on.

I started asking people and they were like, you have to go to London. I spoke to two or three different people about it and they were like, Oh, in London there is a large South Asian community. There's a lot of Pakistanis there, lots of Indians there, and, therefore, tons of fabric shops. And it's funny because, like, maybe Oxford is too posh for these things? Because I thought the art versus crafting argument is more prevalent [in Pakistan]. But then thinking about the fact that I couldn’t find anything, it makes me wonder if it's still a thing in the West, as well. And maybe it is. I don’t know. I'm trying to figure that out through my dissertation, which is not going anywhere.

HK: Oh, my dissertation needs a lot of work! There’s a lot to get done before Hilary Term starts! My final question, then, would be how you want language to function in your work. I was curious if when your work is displayed would you want translations? Would you not want that?

AL: I meant language is obviously a major chunk of my practice. But I honestly didn't think of translation much up until recently because my audience was mainly here [in Pakistan]. Which is strange because I did put up work on Instagram. But again, I didn't really have the need to think about translation. But ever since I was in Oxford, I realized I don't speak my language because no one else speaks it there. So I have to think in English, as well. And I have to talk in English and work in English, which has been a problem because there are so many things that make more sense in my language, and then translating them just completely changes the tone of the work, the meaning, the context. For instance, I was working on phrases that are sort of stereotyped here. Almost like things you would hear every day, but they have so much baggage to them. So if I were to translate them, it would make no sense at all.

HK: Right.

AL: I don't want to translate my work, really. But I do feel that once you put language in writing, there's often a need to translate it because obviously, how else are you going to communicate what you're trying to say? What I've been doing recently is I've been trying to embroider with my mom. And obviously, when we do that, we talk a lot and we talk in Urdu but say bits in English. I think that's interesting because that is language, but in a different way, because you hear it and you pick up things. You pick out the emotion, you pick out the general sentiment of the conversation — the laughter or the warmth or like the way you're sitting or whatever. I think that's been working out well. But I think if I am to use Urdu, it works much better if it's being spoken, not written. Because then it is sort of like random images or pictures to everyone else, not language itself.

—

To see more of Abeer’s work, please visit her Instagram (@abeer.loan).

Hannah Kressel is currently a Candidate for the MSt in History of Art and Visual Culture at the University of Oxford.

An open question: What should diversity and inclusion look like in the cultural sector?

by The Poltern Team

In a call with friends, all of whom are now working in the UK or America in arts, cultural or heritage organisations, the conversation turned to diversity and inclusivity in the workplace. Tavia, who is facilitating a project on the colonial legacies at the Bluecoat in Liverpool (see @bluecoat.colonial.legacies on Instagram for more), asked a few direct questions to the group: how did our workplaces/places of education approach inclusivity and diversity – were there inductions or regular meetings about these topics, had we ever felt excluded, and were the cultures we work in ones that felt actively engaged with creating an inclusive and diverse organisation?

As a personal account, I can’t remember conversations at work or places of study where a culture of inclusivity was openly discussed and addressed. I can, however, vouch that most organisations include this as a concern in their hiring process. As a recent graduate with the job hunt underway it’s hard not to notice the various ways organisations are hiring with diversity in mind, some with anonymous equality and diversity forms, others more explicitly welcoming applications from ‘people who have been typically excluded and are underrepresented in the visual arts’ asking applications to ‘provide any information relating to your personal circumstances that may be relevant here’. And most if not all organisations will, at the bottom of their advertisement, state something similar to:

[Gallery name omitted] has pledged to promote anti-racism in all that we do: the content of our programmes, the culture of our workplace, the diversity of our staff, and the experiences of our audiences. Since 2020 we have been working with diversity and inclusion consultants who are leading a programme of change that involves staff and leadership at all levels of the organisation and will be sustained for the foreseeable future. We are committed to equity and inclusion because these values are right and just. We look forward to receiving applications from all and particularly those from underrepresented groups as we embark on the next chapter of [gallery name omitted] history.

Or,

[Gallery name omitted] is committed to increasing diversity in our workforce and we particularly welcome applications from disabled people, as they are currently underrepresented in the arts sector. In recognition of our commitment to disability equality, [gallery name omitted] is Disability Confident Employer.

The hope is that these impact statements are actually making an impact, but are they? To what extent do hiring methods effectively change the culture of institutions? What does active engagement with inclusivity and diversity actually look like in the workplace? What does and what could diversity and inclusion in the arts sector mean moving forward?

Below are some initial thoughts on the topic from young professionals, to begin our thinking and to open the conversation on the question ‘what should diversity and inclusion look like in the cultural sector?’:

Tavia, Project Facilitator: Colonial Legacies at The Bluecoat

True racial diversity in the arts can seem mythical. In my experience, white people make the major decisions in established institutions. However, I think that many contemporary arts centres are beginning to acknowledge their opportunities to diversify their staff and leadership teams. Some are also starting to think about training their staff to respect differences; for example, equipping them with the knowledge and resources to take anti-racist action.

For me, some arts buildings have been places of exclusion, storerooms of trinkets stolen from my ancestors by their oppressors, places where I have to code-switch. But other arts buildings are transformative spaces that have allowed me to feel absolute freedom. The most important buildings to drive us into the future will be the ones that interpret a fuller heritage than the repetitive narrative we are used to. The arts buildings which recognise the tragedies of Empire but also celebrate its multi-cultural legacies are the ones I’m interested in.

I look forward to the arts and culture sectors evolving their leadership in advocacy and activism, particularly regarding race (and racial intersectionality). I am hopeful for an arts industry with the core purpose of truly reflecting our diverse society and bringing communities together.

Manuela, Recent MA graduate of The Courtauld Institute of Art

The mission statements, job specifications, and recruitment pages of museums and art institutions all have a sentence or two devoted to assuring readers and applicants of their commitment to diversity, equity, and inclusion. These issues are finally becoming a priority, although much too slowly and definitely too late.

But some questions still remain: are these website declarations just a tokenistic way for institutions to say ‘look, we’re trying’, or can (and will) they affect real change?

Perhaps the change we need can only truly happen through much broader, societal, and educational efforts. Perhaps, however, a first step can be increasing transparency, providing data by which we all can track museums and institutions’ progress through the years (click here to see the Tate’s workforce diversity profile 2019/2020 for an idea of what this might begin to look like across institutions). Through this, we might actually see how their words translate into actions.

—

These questions are prompts, but the conversation can be taken much further. We’re looking for you, as a reader, to respond to let us know your experience and your thoughts on the culture of inclusivity.

To respond, email polternmag@gmail.com with the subject ‘Diversity and Inclusion.’ Submissions can be kept anonymous but in a later edition, we will hope to share some if not all of the responses we collate.

Please follow us on Twitter and Instagram (@poltern_) for updates and share our newsletter with anyone who might be interested.