Welcome to the seventh Poltern Newsletter! We took last week off following the submission of our dissertations (!!), but we’re happy to be back with you for #007.

This week’s issue includes “Mind and Body, Agents of Change,” a review of Olivia Laing and Maggie Nelson in conversation at the Center of Fiction in Brooklyn by Victoria Horrocks, which considers the intrinsic loneliness of corporality; a pensive feature on themes of identity and nationality in photographer Oded Balilty’s series “The Forgotten Jewish Veterans,” by Hannah Kressel; a recap of the Ruskin MFA’s here/now publication launch event, and musings on ensuing questions regarding hegemonic history, by Anna Ghadar; an interview with Ruskin MFA candidate Charles de Agustin concerning bullet points, caricatures, and how to decolonize degree shows, by Sarah Jackman.

If you have any questions or comments, please do reach out to us by responding to this email or writing us at polternmag@gmail.com.

Thank you for being here.

The Poltern Team

Mind and Body, Agents of Change

by Victoria Horrocks

In May, the Center of Fiction in Brooklyn, New York, hosted an interview between writers Olivia Laing and Maggie Nelson on Laing’s latest release, Everybody. Laing’s book contains essays on visual art that grapple with what the body is and how to navigate its loneliness. In Laing’s eyes, it seems that the body is both arbitrary and deeply specific, making our individual attempts to contend with our own infinitely trying.

To Laing, the body is a barometer, a tool that can qualify and measure its inhabitant, as well as a home—something chosen, lived-in, and self-made. She compares it to a prison cell but also to a vehicle. Despite these inherent contradictions, her words felt resonant. I imagined the body as a battered studio apartment in need of maintenance, effectively lonely and quaint. Fittingly, Laing referred to bodies during the interview as ‘these lonely units just orbiting other units’.

Inextricably wrapped in conversations about the body, however, were Nelson’s and Laing’s interventions about the systems of which these slippery vehicles are part. While each body is so individual, there is a connectedness between bodies that is universal. The interview fluttered between musings on the erotic body, the traumatised body, and the politicised body, all of which are irrevocably in contact and often in conflict with greater cultural, social, and political ‘bodies’.

And yet, Laing and Nelson wondered what to make of these musings, and what to make of their own work. What can we do with writing concerned with visual art and the body? Nelson complimented Laing often on the evocative and empathetic nature of her prose, but they agreed on the limited actionability of writing. Laing said of herself, ‘I can point out the cancer, but I am not the surgeon’. She followed this resignation by asserting, simply, ‘honey, I am not a politician’, before quickly turning to writing and reading as means to ascertain some answers, some truth. She decided that through writing and reading, we might channel some empathy and sympathy to trigger change: ‘you want people to read the book and then do something with it’, she said.

There is action in making some adverse human experience, some pain or injustice, embodied and visible. But is that all art and writing can do, and is it enough? In the interview, Laing called upon a quotation by Agnes Martin to comment on the changing nature of the writer and artist: ‘It is not the role of the artist to worry about life’. These two poles—the writer/artist as having no political responsibility and the writer/artist as needing to be an agent of political change—appear irreconcilable. After all, empathy and sympathy are fallible tools for change. They can easily centre the self and demand self-comfort, rather than—as Laing and Nelson hope they will—inspire change behaviour or revised world views.

To both writers, it seems there is a disconnect between art, writing, and reality. Laing tells Nelson that ‘reality has given me everything’, yet it is in her writing, some linguistic permutation of experience she sees in art, where she finds truth and connection. Reconciling this disconnect, it seems, would allow us to recognise how art and writing can be actionable in affecting social and political change. Interestingly, Laing’s originary fascination with ‘these lonely units’ divorces the mind from the body, allowing the physical form to remain material, present, and active, while resigning thought to something feeling, intangible, abstract, and ineffective. If we lend the mind the same legitimacy as the body, and if we recognise their inextricable togetherness, then perhaps we can begin to see how changing our minds—be it through the community found in reading or viewing art—can also be a mode of action.

—

Victoria Horrocks is currently a Candidate for the MSt in History of Art and Visual Culture at the University of Oxford.

Oded Balilty’s “The Forgotten Jewish Veterans”

by Hannah Kressel

About 1.5 million Jews fought in the Allied forces during World War II. Among those, 500,000 fought in the Soviet Red Army. Of those who survived, more than 160,000 soldiers, at all levels of command, earned commendations. Over 150 were designated “Heroes of the Soviet Union” — the highest honor awarded to soldiers in the Red Army.

The majority of these Jews remained in the Soviet Union until its collapse 30 years ago, at which point more than 1 million Soviet Jews fled to Israel. Nearly 7,000 Jewish Red army veterans — the majority of those alive today — among them. On May 9 of every year — Russia’s Victory Day — they march through the streets of their cities, waving flags and sporting coats heavy with medals. At the conclusion of the annual parade, they return home, shed their uniforms, and resume life as immigrant pensioners; the achievements of these veterans closeted with their military fatigues for another year to come.

In his series, “The Forgotten Jewish Veterans,” Associated Press photographer Oded Balilty captures these veterans, in the homes of their new nation, dressed in the uniforms of their native one. He explains that although “Holocaust survivors frequently speak about the horrors they experienced … Soviet war veterans arrived in Israel as pensioners, and most never learned Hebrew. Few Israelis know their stories.” His photographs aim to document the presence of Jews in the Red Army, their achievements, and their current status in Israel: largely unknown, many neglected. “They return home to their modest apartments, where some tick off the days in solitude and poverty,” Balilty explains.

His photographs feature these veterans in their apartments, calling attention to a dissonance between their youth and their current reality. Their proud stances and sharp dress loom larger than their ascetic surroundings. Round and colorful medals lay like scales against their crisp suits. The badges gleam in the light. However, the neat lines of the military fatigues the men don dissolve into proletariat furniture and rumpled sheets. They sit at bare tables and sink into the thin padding of modest couches and mattresses. Balilty beckons the portraits of nobles in the composition of his photographs. The surroundings of the veterans, however, are stark counters to his suggestion of virtuosity. One man sits before a table studded with platters of pastries, vegetables, and meat. To his right are two bottles of wine. All of it remains untouched. Another man stands over a table; his hands rest against the table’s taupe cover. A bowl of fruit rests on the table before him, brimming with pomegranates and loquats. Although he wears the garb of his Soviet youth, the food before him is evidence of his new home. The scenes are so incongruous it seems the men could have been photoshopped into their surroundings.

Balilty’s images are melancholy. His photographs put forward a rapidly fading history presented within the confines of humble apartments. These are war heroes whose perseverance for their people is overlooked, perhaps shrouded out of shame and sadness at the history and ultimate reality of Jews in the Soviet Union. Through his photographs, Balilty awards honor to a group of Russian Jews while proffering accountability to a nation that seems to have forgotten them.

—

For more of Balilty’s work, please visit his website here.

Hannah Kressel is currently a Candidate for the MSt in History of Art and Visual Culture at the University of Oxford.

Here/after Publication Launch Event

By Anna Ghadar

On Thursday, June 24, I had the opportunity to visit the Ruskin MFA 2020-21 cohort’s here/after publication launch event at OVADA Warehouse in Oxford. The exhibition supplemented the cohort’s online degree show, which you can view at pixelmeat.co.uk.

The publication features work by this year’s Ruskin cohort and offers some tactile and haptic engagement in a year when visiting degree shows in person is still not quite in our grasp. Here/after, its accompanying launch event, and the online degree show each offer valuable commentary on the future of degree shows and their inherent limitations pertaining to accessibility and ephemerality. On pixelmeat, the online platform for the exhibition, the artists participating in this year’s MFA program note their own complicity in power structures by engaging with institutions with colonial legacies. The artist collective’s statement suggests we confront our own complicity in systems of oppression to gauge successes and limitations of working from within the discipline to decolonize from the inside out. These meditations are conveyed both through the collective’s statement and the dialogic online, in print, and in-person exhibitions, in which each artist’s voice is clear in marking their own critical commentary on the structures of power they confront and attempt to deconstruct throughout their work.

The exhibition underscores the cohort’s “myriad of identities and political positions” while highlighting their collective goal of actively contributing to the decolonial discourse in academic and visual arts spaces—and, of course, the overlap between the two. A shared narrative between artists is their solidarity against white supremacy and colonial legacies. These are, of course, timely commentaries that mark the visual history produced within the past year. The writing within the publication, as well as the works on view, also speak to the ebb and flow of traction in activist endeavors. They note successes and condensed moments of progressive change while refusing to overlook the moments of slowed progress or even failures in attempting to move forward the decolonial project (both in Oxford and globally).

I agree with the cohort that admission of complicity in power structures is a critical reckoning in effecting change. In fact, our benefiting from such institutions needs to be addressed as well. The joint message of the exhibition and publication prompted a question I’ve been asking myself—is it possible to disrupt institutions from the inside? And is it possible to decolonize art history, the museum, or, for that matter, any space or discipline that plays a part in upholding hegemonic history? As someone who has recently completed a degree from the oldest extant anglophone university—a space that has flourished through colonialism—I maintain that I am a beneficiary of the institutional power. Given my own personal and professional goals, coupled with my privileged positionality within this system, I hope the answer is yes. Following the launch event, I was left with the lingering question: is it possible to decolonize institutions from within? If so, how? Here/after takes the critical first step towards this mission through acknowledgment and critical thinking.

—

Anna Ghadar is currently a Candidate for the MSt in History of Art and Visual Culture at the University of Oxford.

Interview with Charles de Agustin, Ruskin MFA

by Sarah Jackman

It was a cold crisp day, birds perched in sparse tree branches were in full voice, and the low sun caught the golden hues of Oxford’s colleges. After a walk around Christ Church meadows, Charles de Agustin told me about his work at the Ruskin School of Art - one of the few university studio spaces to stay open during the national lockdowns of 2020 and 2021. He’s been exploring a wide range of material and theory, including caricature, bullet points, whiteness, decoloniality, repatriation, and Oxford’s history of Empire sustained by the built environment of the city by which we were so engulfed.

Charles: I’m currently interested in a broad conceptualisation of caricatural logics, narrative logics, and the violent reductionism of character. So, I’m rooted in print caricature, but my research has been more specifically located in Oxford this year, looking at Shrimpton’s print shop and his caricatures in this story called ‘Cool Britannica’ from the mid-late 1800s. The print shop site is now a cheesy Oxford memorabilia shop. Funny what’s currently in the previous site of this shop for local caricature, drawn by current Oxford undergraduates! Of course, I don’t understand most of the references in the caricatures, but there’s kind of this playfulness and self-awareness of the grandeur of Oxford, playing with the image of the dons and the idea of the Oxford undergraduate.

Building on this, the main thing I’ve been wrestling with is kind of caricature in a local context and then bullet points. I’ve been trying to make them make sense together…but it's not going the right way just yet.

Sarah: Tell me more about this relationship between bullet points and caricature, and why aren’t they working together?

C: Well, I’m interested in the utilitarian origins of bullet points. You can’t really track down their origin too easily, maybe the easiest is PowerPoint, or at least that’s how we think of them popularly. I’m interested because they function in the same way as caricatures violent reductive logics.

S: Short, sharp thoughts?

C: Yes, and also how you’re forced to fill in the holes between bullet points. As you were saying, fill in the holes between a print caricature and the features that are exaggerated to come to your own conclusions. These are both things that are designed to be easily consumed.

S: There’s also this historical specificity that comes with caricature that is interesting because they’re meant to be these easily readable transferable commentaries, but you have to really know that political environment to understand the critique. Do bullet points have the same historical specificity?

C: Exactly, I’m in an ongoing struggle with these topics and areas like historical specificity and not knowing the extent to which being ahistorical is appropriate. I think this caricature of being very temporally situated is very relevant to bullet points. You can look back on a power point presentation from your middle school, or even from a week ago, and chances are you’re going to have no idea what’s going because you’re in a frantic state making notes, and you look back and think what the fuck was this lecture on! So, my struggle is whether to combine the two is a conflation, whether there is anything productive about drawing this link, but surely there is, there’s something about them just being very efficient!

In terms of artistic exploration, I’m interested in flipping that efficiency on its head. In theory, they’re supposed to be a great tool in terms of attention economy, so I’m trying to use those tools against their own logic. It’s fun, it’s really fun, and I think it's productive.

S: So, how do you use your medium against itself?

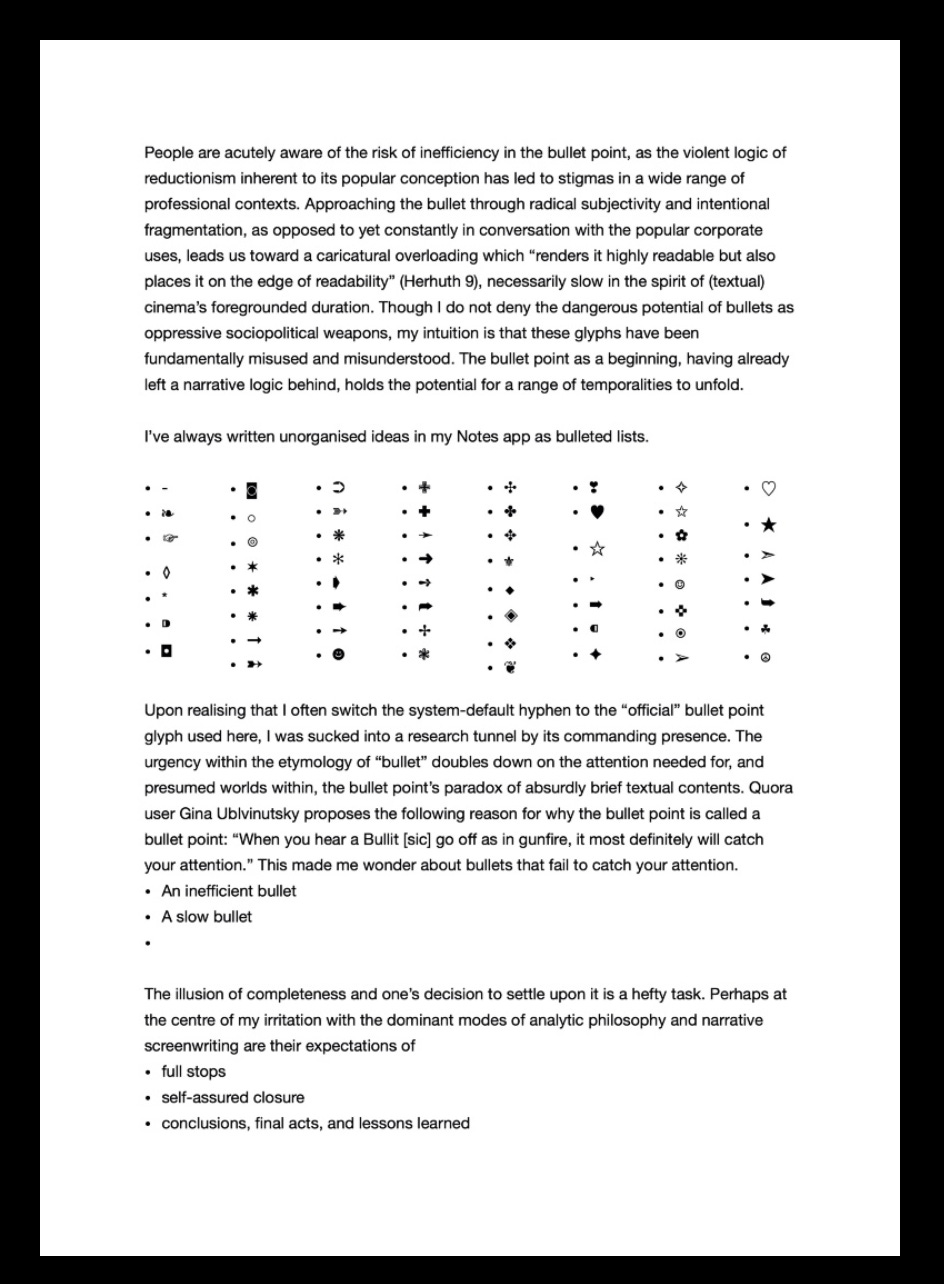

Charles shows me the beginnings of an 11 or 12 min video of short snippets of changing white bullet points on a black background, each with a new piece of information unrelated to the last.

C: This might come off as totally chaotic. It’s very structuralist, quasi diaristic, quasi contemporary, engaging with social issues but obviously with no connection point to point. I’m interested in what goes on in that little white or black circle…of course, all this text could work without the bullet there, but they’d be totally different. Instead, these bullets command and demand that you assume there is more within the text which is the whole point of poetry, but this is something different because of the utilitarian nature of power points and bullets.

S: It’s interesting seeing it in film format because as the viewer, you only get a limited, ephemeral period of time with those words…time feels two-fold, you only get so long with a bullet point anyway, and then with film, you’re only letting the viewer linger on it for a shortened period of time?

C: So again, that is what I’m struggling with…I did this performance for zoom where I had a visible presence on screen, and I was silent, sitting there silent on-screen, but the assumption was that I was going to lead people through the powerpoint, but it became clear that my presence was the least interesting thing in the work and it was locating the bullets less in my own social positionality and more in the viewer’s position.

S: How self-consciously do you play with the relationship between author, viewer, and your own relation in your artwork? I know I’ve seen some of your undergraduate work where you see yourself as a caricature of yourself, acting as Charles Prigmore. I was interested to hear how your own positionality as an artist and protagonist changes your relationship with the viewer.

C: Caricature was a more vague interest in those works for my undergrad; this thing of caricature was a means of exploring white performative wokeness, which I think I was thinking a lot about in relation to white victimhood in the context of the American artist Jordan Wolfson. Wolfson is complicated. He identifies a contemporary pollution of white victimhood which in liberal or even leftist circles is related to Robin DiAngelo’s popular term ‘white fragility’. It’s all so multi-faceted and confusing, but I am interested in the performance of white wokeness and how it inherently fails itself. It’s uncomfortable because I’d done two or three of these live performance things where I was playing on my own positionality of being male and white and the history of those identities.

S: Were those performances to expose or challenge or change those positionalities of white victimhood or fragility? It feels like we keep exposing all these conversations and narratives about whiteness and wokeness and fragility and victimhood, but they’re recycled; they're not changed. So, with your work, how do you combat that relationship? By exposing and changing these narratives?

C: Yeah totally, what’s the distance between critique and just reproducing the subject. In my performances, I got myself into a situation where people who didn’t know me came out of them thinking, ‘wow what a fucking asshole’. I would hear down the wire these things just weren’t landing, which is a big problem because not only is it bad for me (my ego can take a hit), but it’s bad for the work because it’s not what it’s trying to do. I don’t know if the sense of play and dry humour that I try to maintain is appropriate, and it just kind of goes back to broader conversations of echo chambers and questions of who I am really speaking to. I think that’s why I’ve started to show myself less explicitly in the works, even though it’s kind of talking about the same things, really.

S: Do you think separating yourself from your work is landing more, speaking more to the audience you want it to?

C: I don’t quite know yet, but I think it allows people to think more abstractly about me, and it's allowing people to think more abstractly about the content. Thinking about my cha..ch..ariture…it's funny I’ve been thinking so much about caricature that I can’t say the word c-h-a-r-a-c-t-e-r…character!

S: Yes, self-reflection on your character and who you are speaking for and speaking to.

C: The worst thing would be to be speaking only to white people, which is not my intention, and I think so far my work has been legible and successful with everyone. But, building on all of this, there are two things to touch on. The first makes me think of the DPhil at the Ruskin. In their research symposium, they were having this conversation about how this field of critical whiteness studies is tired now, and I think people generally think it doesn’t make sense in relation to the black radical traditions. Even if you think you’re finding productive subversion in researching or talking about whiteness and its failures etc., why spend time doing that when you could be putting energy towards uplifting marginalised and black voices, artists, curators, and so on. It’s also related to these conversations around decolonial, though at least in a university context. There was this great tweet that I read a few days ago; it’s not original, but it's good. It reads: ‘sometimes the answer is not doing more research, sometimes the answer is looking to redistribute the resources that enable research.’

S: Yes, can you feel yourself moving towards a desire to work to produce redistribution methods, thinking how does my art operate to facilitate this?

C: There was this great visiting speaker at the Ruskin, Ayanah Moor, who was a print media artist and black queer woman. As a tenured, full-time professor, she was talking about and acknowledging how comfortable her own situation is, but as a result, when she gets commissions, no matter the scale, oftentimes her first thought is ‘how can I bring my friends into this project who need this funding more than me’ or she’ll try to entirely redirect that funding. I think that’s a beautiful way to work, and I think the most effective way you can work with an institution and negotiate the power relation between an arts institution and your role as an artist. From the institutional standpoint, it is kind of insulting, but I think it’s really good. It’s also playing with a traditional expectation of authorship, this expectation surrounding commissioning particular artists.

It’s a much wider thing. I spend too much time on twitter in general, and I follow Dan Hicks, and I’m thinking about his new book (The Brutish Museum: The Benin Bronzes, Colonial Violence, and Cultural Restitution). I’ve read a lot about it but not yet actually read it, but it tackles this whole thing of the most explicit example of colonial object restitution and repatriation. From my perspective, it seems like such an easy answer, you know, it doesn’t take a rocket scientist to look at an object's history and to say this isn’t from here, England, and clearly was not acquired in a legitimate fashion, it should be given back to whatever area it came from. It’s a fantasy to think that there’s not an institution in whatever area that can care for objects, and I just think it’s tied up with the British Empire needing to hold on to—

S: —the lingering empire of knowledge and possession?

C: Yeah, it lives in the architecture and the objects around us.

S: Speaking of our physical environment, where are you on the statue of Rhodes?

C: Fucking yeah, take him down. I guess though, then it becomes this thing, if you take Rhodes down, well look around you, we need to fucking bomb Oxford!

S: Totally, and what about historical erasure? You’d give the bronzes back, but how would you keep telling that part of their object history, of colonialism, the impact, the damage done?

C: (laughing) I just don’t know.

S: It seems you’re quite heavily grounded in theory and working through others’ theoretical ideas; how do you find the balance with your own ideas? Or sometimes is it just feeling not theory, sort of well, of course, the bronzes should go back, theory doesn’t have a say in this?

C: It’s a sticky relationship. I do try to ground myself in things, and it’s a whole other topic, but I’m pessimistic about social issue art or the social agency of art for change.

S: Yet, doesn’t a lot of your work focus on social issues?

C: That’s just my internal and eternal struggle. I think my answer to that is that I think, [given] our place in a research farm as historians or art producers, these conversations need to be moving on in a variety of ways. I think it’s a strain of neoliberalism, and I’m contradicting myself, but there’s a strain of neoliberalism that the only way for social progress is being on the streets making tangible change because the definition of tangible change is elusive and shifting. I think the only answer for artists who spend most of their time creating is how you’re supplementing that work, whether that’s financial or putting time into organisations or whatever.

To go full circle back to this object thing and caricature, I’ve been spending a lot of time with the emperor heads at the Sheldonian Theatre in Oxford, and I’m interested in them as these ghostly objects of the Empire. I’ve spent a lot of time researching them: the current ones are the third generation put up in 1972, I think, and the original ones were 1669, commissioned by none other than Christopher Wren, who seems to have done the whole city! I just found it so fascinating that they have a caricatural form, but they’re not caricatures of anyone, in particular, so then what are they caricatures of? The only thing left is that they are just caricatures of that positional gaze, of Empire and of a presumed whiteness. There’s a humour to that because they’re so absurd – I mean, look at their faces, they’re ridiculous, hilarious! It’s also this thing of the university as a place of knowledge production as they’re protecting the Sheldonian Theatre where degrees are certified etc. I’m more interested in the previous generations of them and how they were haphazardly discarded across the city, firstly in the junkyard and then across colleges. There are two in the university arboretum (botanical gardens), and they’re even more absurd as they weren’t cared for, so they’re decaying, and they look even more terrifying. Some are more recognisable than others, but some are these rotting figures of Empire, and I’m interested in them as ghostly characters and custodians of Empire because Oxford has so many literal associations to Empire.

S: I’m now desperate to find some of these scattered heads. Are you managing to incorporate them into your current work?

C: They were actually the first things that drew me into Oxford. I knew I wanted to think about these things in general at Oxford, but in terms of how I’m using them, they’re the thing that has taken me the longest to figure out and work with because they’re really difficult. I did finish the first draft of something that uses them as a spirit character, where they speak through these early cinema-esque title cards, and they talk about these ideas of white victimhood. They’re these social justice warriors trying to dismantle their pride and everything that Oxford stands for. It’s also all about stillness and time. I’ve used them as well to work through ideas of pose with a couple of my friends alongside movements that were taken from this Shrimpton caricature collection. They did poses and movements, and people are enacting these in subfusc and ideas of stillness.

Time has been so fundamental too. It’s so great that we’re at Christ Church because of the Christ Church timezone. It’s so fascinating, incredible, and I barely even know how to speak about it because it’s so overwhelming—it has a nostalgic energy for pre-industrial Europe that’s now a novelty. There is something of the grandeur, or arrogance, of the gesture and the insistence of it that is so overwhelming that when I happen to hear it, it just freezes my movement and thought, and there is something there in relation to everything we’ve been talking about. It’s also so different from Regents Park College. This difference between colleges, I think, relates to the British Empire. The fragmentation of the administrative board of the University is so separated into its own world -departments, colleges, programs - and nobody really knows how the place works except the people at the top. I think that is the same way that an Empire spreads or how white supremacy operates as a process of silence and not knowing how things work.

S: Does film allow you to network all these ideas together, do you think, more than any other medium?

C: More and more, it’s the opposite because we’re trained in starts, middles, and ends, and it makes it quite difficult unless you’re steeped in non-narrative and experimental film to latch on to a film that is pulling together potentially random shit. I think their relatively short history of cinema makes it difficult, and it's why I’m at a point where I’m not quite sure if my 20 min film is working cohesively or if it needs to be more episodic or a series of one-minute video pieces. Part of me disagrees with what I just said, and some of my favourite experimental films do pull together disparate ideas, and they can do it really well. I think I’m just cautious about this idea of conflating things and their value and not giving them the time and attention they deserve. I think that’s why I like the Sheldonian heads because they are kind of disregarded, and I want to treat them—

S: —Like, they're alive? Bring them back to life?

C: Yeah, exactly, to bring them back to life. In fact, I think they are still alive. I keep thinking about the older generations and our ability to say they’re in the past when in reality they’re right fucking there. They are alive. They feel alive.

—

For more on de Agustin’s work, please visit his website here.

Sarah Jackman is currently a Candidate for the MSt in History of Art and Visual Culture at the University of Oxford.

Please follow us on Twitter and Instagram (@poltern_) for updates and share our newsletter with anyone who might be interested.

PS—we’re doing an open call for reviews, features, interviews, and creative writing. If you have work that confronts issues in art history and the visual arts, email us at polternmag@gmail.com. We’d love to feature it 📝