Welcome to the fifth Poltern Newsletter!

This week’s issue includes an excerpt of “The Body in its Absence: Three Works by Felix Gonzalez-Torres,” a heart-wrenchingly beautiful segment by Kate McBride; “Mirror Effects,” an attentive and nostalgic creative writing piece on portraits by Salomón Huerta, written by Theodore Elliman; and two (!!) special features showcasing dissertation topics by the University of Oxford MSt in the History of Art and Visual Culture 2021 cohort: “The Art of Cooking: A Guide to Cookbooks in Aesthetic Practices” by Hannah Kressel and “Occupying Space: Deconstructing the Ideology of the White Cube” by Anna Ghadar. Stay tuned for more insight into the exciting projects by this year’s cohort in Issue #006 📝

If you have any questions or comments, please do reach out to us by responding to this email or writing us at polternmag@gmail.com.

Thank you for being here.

The Poltern Team

The Body in its Absence: Three Works by Felix Gonzalez-Torres | Feature

by Kate McBride

Félix González-Torres’ work is corporal and confectionary. It takes the marginalized body as its foundation, circling delicately around themes of grief, loss, morality, illness, and time. At a historical moment where the AIDs epidemic was ravaging communities internationally, and a disease diagnosis became a life sentence, González-Torres delved deep into bodily trauma while rarely depicting a figure. At this time, and perhaps still today, the queer body was a battleground both politically and physically. In this way González-Torres falls into the categories of minimalism and conceptualism, but also activism. His work begs the question: are depictions of the ‘other’ more palatable in mainstream culture when they don’t depict actual bodies but only insinuate them?

Born in Guaimaro, Cuba, in the 1950s with a childhood and adolescence spent in Puerto Rico, González-Torres entered the contemporary art canon in the late eighties and early nineties after moving to New York City in 1979 and continuing his art education both in the classroom and out of it.[1] In 1983 his first solo exhibition, A Second Reading, took place at Printed Matter Inc., a renowned and still thriving New York institution that celebrates printed paraphernalia, including both books and visual art.[2] Thirteen years later, with numerous additional and international presentations of his work, the artist would perish due to complications from AIDs, following his partner, and followed by a generation of others. It is heartbreaking to consider the work his brilliant mind could have continued to create if not for his tragic death in 1996 at the age of thirty-nine. Despite his untimely passing, González-Torres has continued to receive critical acclaim, been the subject of major retrospectives and academic scholarship, and has represented the United States at the Venice Biennale.[3]

At first glance, Felix González-Torres’ works are appealing, ethereal, gentle. Pastel, translucent fabrics trace windows and pool elegantly on the floor, jewel-toned wrapped sweets reminiscent of holiday treats sit in extravagant piles, lit light bulbs pirouette from the ceiling grazing and finding a seat on the floor, shimmering colorful plastic beads hang in doorways with a satisfying tinkle and rattle as visitors move through them. One could easily pass through a gallery of his works, delight in the color, pocket a sweet, skim a hand along Mardi Gras-like beads, and move on. But the works are not without content, both political and personal. González-Torres uses this charm as ‘a tool for seduction and a means of contestation.’[4]

However visually appealing, González-Torres’ creations are deceptively simple and sweet. A cursory glance at a title or wall label quickly indicates the depth and darkness behind these minimalist constructions. As an artist statement from 1988 would explain, in his work, ‘the fictional, the important, the banal and the historical are collapsed into a single caption.’[5] The lightbulbs slowly extinguish, the sugary piles denote the weight of human bodies, a compression is still visible on the pillow where a head recently lay on a photograph of a bed. Despite the lack of figure, these works indicate the immediacy of grief and heartache while also speaking to the artist’s ‘distrust of representation as ideologically laden.’[6] The audience is brought through pleasure to reality: the inevitability of death, the violence of humanity, the negligence of our political leadership. And yet there is comfort to be found in color and familiarity, a bitter pill wrapped in ruby, emerald, gold, and sapphire. This tender treatment of loss is heartbreaking and compelling, and perhaps more effective artistically and politically.

González-Torres installations are often replicable, made of quotidian objects, and nonetheless deeply poignant. In Untitled (Perfect Lovers) two generic, mass-produced clocks are installed next to each other on a blank wall. The clocks are black framed, thin plastic variants, or in other iterations white chunkier frames, a slightly different breed, but always reminiscent of something you could pick up at a hardware store or IKEA. They are always installed with their frames gently resting against each other. They are not merely adjacent; they are touching, like partners, their lives don’t exist separately from one another, and together form an infinity symbol.[7] The clocks are installed at the same time, fitted with identical batteries, and yet eventually, they slip minorly out of sync.[8] One clock’s hands might point to 3:15 while its partner has skipped a little ahead, registering 3:16 or 3:17. These clocks are left to run until their batteries expire, one inevitably stopping slightly before the other. And yet, though asynchronous, they remain together, intimate, a couple.[9] There is no explicit reference to queerness, and as Judith Butler says, the gender and sexuality binary operates societally to ‘consolidate and naturalize the convergent power regimes of masculine and heterosexist oppression.’[10] As such, in a shockingly pure and painful metaphor for partnership, love, and loss that removes gender, sexuality, and the body, González-Torres moves away from stigma to create room for empathy.

These works function as memorials, and like other more traditional ceremonies of grief, they are shaped not just by the deceased but by the environment and the participants. The audience participation feels elegiac, and in ways familiar, despite the playful visual nature of many of González-Torres’ installations. As a result, González-Torres’ ‘recuperates the homosexual body – traditionally exiled, in overt form, from artist representation – and grants it presence, subjectivity, and agency within visual culture.’[11] Additionally, there is a solemnity to the museum and gallery space. These works invite us to both break the rules by touching and taking the art, and also engage the sanctity of display to invite us to look deeper into his abstractions. It is as if without the body represented, the audience is, in fact, able to get closer to the real, experiential feeling of the body.

In ways, González-Torres’ works are reminiscent of vanitas paintings. Within his contemporary poetic sculptures and interventions, there are clues that point to mortality, to the vanity of our worldly existence, to the temporality of the body.[12] Like the first impression of a vanitas painting appearing as an attractive still life from across the room, the aesthetics and color of his work make the subject more palatable. In his work, we find ourselves even convinced to consume the subject, another reference to the pervasiveness of morality, or perhaps in connection again to vanitas, the ‘worthlessness of worldly goods and pleasures’ symbolized by cheap candy available ad infinitum.[13] It is only with closer examination, much as with a vanitas painting, of his creations that the subtle iconography of death appears—themes of liminality, threshold, the flux of life, transience, temporality, lamentation. We see the reference to the ‘lifting of the veil’ in his curtained pieces, the attempts at casual displays of items that have in fact been very carefully arranged in his candy works, the symbolism of a recently blown out candle in his light bulbs works and the clear reference to time and death in his clockworks.[14] In this way, many of his works function as memento moris, appetizing depictions of destruction that serve as a warning or reminder for the audience.

Despite the deep anguish and suffering elucidated here, there are also messages of profound hope and gratitude for life itself in the works. There is no trace of nihilism. An arguably horrific and unfair card was dealt to González-Torres, his partner, his artistic community, and yet in his writings, there is an optimism present that is also sometimes surprisingly apparent in his work. As he wrote to his partner Ross before his death:

Don’t be afraid of the clocks, they are our time, time has been so generous to us. We imprinted time with the sweet taste of victory. We conquered fate by meeting at a certain TIME in a certain space. We are a product of the time, therefore we give back credit were [sic] it is due: time.

We are synchronized, now and forever.

I love you.

The candy pile does not ever deplete, despite being picked away at by the public daily, the veil is never completely lifted; we are just asked to pass through it repeatedly and appear from the other side whole, the clocks run out of sync with each other, but when one preemptively stops ticking it is not removed from its place of intimacy next to its partner. While his works refer to time in the sense of loss and mortality, they also not intended to lead us to despair, but instead to not take for granted the time we are given.

—

Kate McBride is currently an MLitt Candidate at the University of St Andrews.

[1] Boone. “Félix González-Torres.” [2] Spector. Felix Gonzalez-Torres. p. 201. [3] Spector. Felix Gonzalez-Torres. p. vii. [4] Spector. Felix Gonzalez-Torres. p. vi. [5] Miller. ‘A Colossal New Show Revisits a Conceptual Art Icon.’ [6] Spector. Felix Gonzalez-Torres. p. vii. [7] Miller. ‘A Colossal New Show Revisits a Conceptual Art Icon.’ [8] Ibid. [9] Spector. Felix Gonzalez-Torres. p. 143. [10] Butler. Gender Trouble. p.46. [11] Spector. Felix Gonzalez-Torres. p. 156. [12] Tate. ‘Vanitas.’ [13] Ibid. [14] Ibid.

Mirror Effects | Creative Writing

by Theodore Elliman

On my first night of vacation, I asked my roommate to shave my head. I wanted to stage an intervention in my life, to mark my freedom from work, to feel lighter as certain weights became lifted. The weather grows warmer. Bodies are becoming inoculated against Covid-19. The city reopens. So here was my personal contribution to positive change in my life – this gesture of shedding and renewal.

It occurred to me after the haircut that I had never before seen the shape of my head or the look of my scalp. Neither was particularly remarkable, but how strange not to know something that had belonged to me forever, that I carry every day. And how affective it was to behold this elusive part of my body.

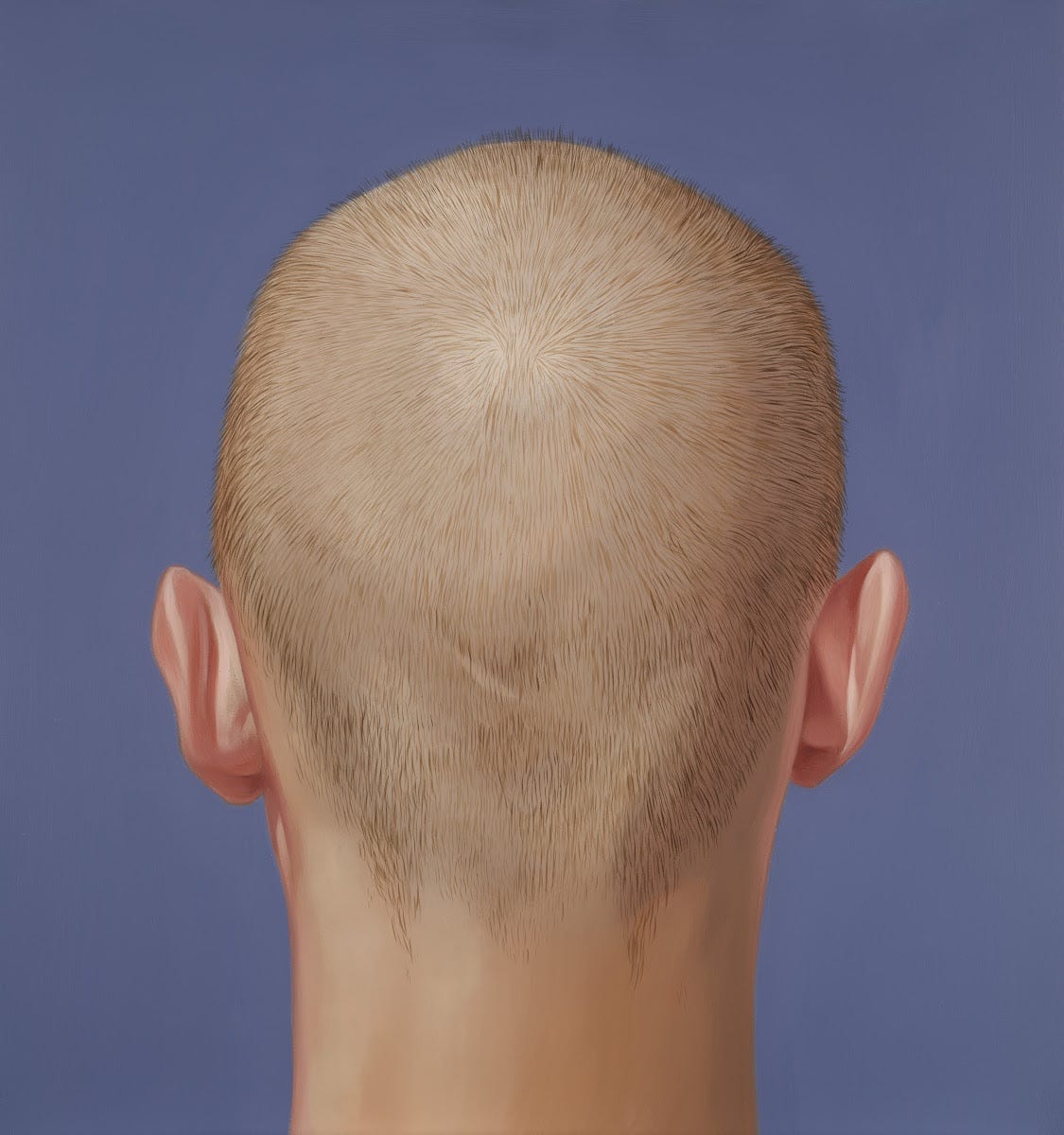

This is a fascination I share with Salomón Huerta whose early portraits reveal the unexpected splendor of a shaved head. On small, square canvases, he painted anonymous male subjects turned away from the viewer. We see just the back, cropped at the base of the neck, with an inch or two of margin on the sides and top. The portraits are rendered in exquisite detail, so highly realistic, quasi-photographic. Huerta seems almost forensic in his studied approach. There is no visible trace of his hand, neither on the heads nor on the backgrounds, which are flat, uninflected fields of bright color. The contours of the form are crisp. The strands of hair look prickly to the touch. Parts of the ear are translucent. There are scars and uneven hairlines and waxy regions that gleam. Huerta’s is a portraiture committed to precision, that insists on exactness. It’s a powerful painting of austere realism.

“I wanted,” he said about these works, “to tone everything down so it was like a mirror to the viewer.” A mirror that reflects what is impossible to see on one’s own. A mirror that shows something uglier and more abstract, reflecting a dirtier kind of truth. In the absence of facial features and expression, Huerta leaves us with a blankness that exposes our own assumptions, prejudices, and values. By giving us so little to go off of – not an eye, mouth, nose, or context – we scrutinize the head and conjure a type or a trope, leaping to likely problematic conclusions.

This is exactly his project: to present non-confrontational images that impel us, nonetheless, to confront how we perceive and assign identity. “I’m thinking about mug shots. I’m thinking about the obsession that the dominant culture has with the ‘other.’ How I articulate that,” he said in an interview “is by painting these figures with so much detail and clarity to reflect how closely these people are looking.”

Huerta was born in 1965 in Tijuana, Mexico. Four years later, he immigrated to Los Angeles with his parents, three brothers, and four sisters. Together they lived in Ramona Gardens, a public housing development in the Boyle Heights neighborhood of East Los Angeles. Huerta recorded many of his childhood experiences in a series of anecdotal texts published in a book called Let Everything Else Burn. He inscribes his upbringing visually too in these portraits that evoke the malign practices he witnessed of racial profiling, criminal interrogation, and public surveillance.

He introduces and negotiates these concerns with total control. In a 2001 interview, he discusses his approach: “I want to make them as sensuous or luscious as I can.” The orange, blue, red backgrounds. The smooth, poreless skin. The erotics of the neck. “Then,” he further explains, “when I pull them in, they see there’s something tragic going on.” He speaks of his aesthetics as the laying of a snare. I completely fell for his trap.

I first encountered Huerta’s work when I was eight years old, in 2005. My godmother took me to an exhibit at El Museo del Barrio in New York City where his work was being exhibited in a group show. From this early, formative memory, I recall just the astonishing color and cropping of his canvas. Only now, all these years after that marking impression – Huerta having pulled me in – do I see the politics in his portraits.

I also now see a part of public life that the pandemic has taken away. When I look at Huerta’s paintings of bodies with backs turned, I am reminded of the experience of being in a crowded place, among a stack of people. I am in a theater. I am in a lecture hall. I am standing in a line to swipe my MetroCard or pay for groceries. I am somewhere in a swarm, staring at the back of someone I don’t know, seeing a freckle behind their ear. I am occupying a shared space where an unassuming intimacy develops between myself and the stranger before me.

In this way, Huerta’s portraits function as landscapes. They transport me elsewhere. It’s an amazing achievement that without any contextual signifiers – just a plane of color – the paintings manage to take me to specific places of gathering and congestion: a voting poll, a pew of a church, the quad at my college graduation that never transpired.

If these portraits posture as landscape, then the heads become a kind of geography. They are sketches of a terrain that is uneven and lumpy, an earthy surface with knolls, ridges, and craters. They are like topographical maps where scars and cysts are boundaries and slopes. Or perhaps it is more instructive to observe the heads from further away. Then, they become planetary, as orbs, set against an abyss of color of an outer space. Huerta’s work invites this scalar movement, shifting from near and far, from here to there.

I wish I could see all of the portraits on a wall at once. I imagine the canvases expanding and my eyes, like kaleidoscopes, multiplying the figures in every dimension. The characters would push out of the frames. They would have torsos, legs, shoes. They would have freedom. They would have faces. They would have each other.

—

Theodore Elliman is a writer currently based in New York City.

Quoted in Elizabeth Ferrer, “Mirror/Image: Paintings by Salomón Huerta” (Austin Museum of Art, 2001), http://www.tfaoi.com/aa/2aa/2aa597.htm.

Interview with Bill Kelley, LatinArt.com, 2001, https://www.latinart.com/transcript.cfm?id=7.

The Art of Cooking: A Guide to Cookbooks in Aesthetic Practices | Dissertation Preview

by Hannah Kressel

This dissertation offers an aesthetic analysis of the way cookbook authors construct place and time through their cookbooks. By positioning the cookbook like this, I confront the way these texts have been systematically excluded from art historical discourse, despite their similarity in form and efficacy to various contemporary creative practices.

Although cookbooks are not typically conceived as aesthetic or artistically concerned texts, we interact with them similarly to how we interact with participatory and relational art. That is to say, we expect to read about actions executed by the creator (artist, or in this case, author) with the intention of being able to recreate those actions. Staging and reproducibility in a defined act, which can transcend the bounds of space and time, are at the center of both cookbook practices and relational and participatory art practices. Cookbooks, and the eating experiences they function as manuals for, mirror the etiquette of performance practices, making them worthy of aesthetic evaluation and analysis. These repositories of recipes and taste function as series of profoundly relational and participatory culinary performances, both reflecting the author’s act of cooking and guiding the user of the cookbook through their own performance of cooking. When delineated within the cookbook construct, the act of cooking becomes a coordinated performance of sensing, tasting, and locating.

It is a consideration of the relational power of cookbooks as self-aware framing devices and initiators of culinary performances, which is the focus of this dissertation. In each chapter, I parse through the various components that make up culinary performances and how they are distilled through the object of a cookbook into participatory artistic endeavors. Cookbooks are an ideal method for determining the material character of culinary performances because they function as repositories of human taste and are locations of shared sensations where collective affective dynamics have material (and materialized) traces. In other words, they function as printed, textualized accounts of creating locale through taste and as manuals for users to self-consciously re-create the experience of defining space through tasting and digesting.

Divided into three sections — the Cookbook, the Recipe, and Food — I address how cookbooks construct boundaries in both time and material to create intimate, domestic, and contingent spaces through the recipes they offer to readers. In each section, I demonstrate how these spaces — forged through the structure of cookbooks, the format of recipes, and the consumption of cooked food — are consummate examples of performance art and collective social practices, embodying crucial tenets of participatory art and relational aesthetics.

As I will demonstrate in this dissertation, the cookbook is an ideal substrate for artistic endeavour because it sensationalizes, distills, and amplifies an essential aspect of human existence — eating — into a self-conscious, aestheticized act.

The goal of this dissertation is to assess the cookbook as a tool of aesthetic practice. In addition to documenting the similarities in function and form between codified performance art practices, art books, and cookbooks, this dissertation suggests the way books function as central to creative practices, rather than supplementary materials. Although not the focus of this dissertation, the analysis presented here suggests the way gendered hierarchies continue to affect what is included within the art canon and how creative objects are valued. Additionally, this dissertation offers strong support for an increasingly interdisciplinary art historical discourse by engaging both cookbooks made by noted artists and cookbooks made by chefs and home cooks.

—

Hannah Kressel is currently a Candidate for the MSt in History of Art and Visual Culture at the University of Oxford.

Occupying Space: Deconstructing the Ideology of the White Cube | Dissertation Preview

by Anna Ghadar

In Occupying Space, I’ll be exploring the limitations of Brian O’Doherty’s series of essays initially published in Artforum in 1976, titled Inside the White Cube: The Ideology of the Gallery Space, as they pertain to issues of race and identity. O’Doherty asserts that the white cube—a term he popularized—is a modern invention that suggests ‘neutrality and purity.’ He argues that it is a hermetically sealed space that dulls critical engagement with pieces shown in it by ‘artifying’ said works. Further, the space has a religiosity to it and, ultimately, upholds institutional values. Art historians, curators, and cultural theorists continue to reference this text. However, the author’s overall approach is totalizing and does not allow for nuance. In one essay, O’Doherty writes, “Is the artist who accepts the gallery space conforming with the social order?” He poses the question rhetorically, assuming it to be impossible. I define ‘accepting’ the space as recognizing its implications and still choosing to engage with it. Thus, in response, I ask: can one refute the social order by exhibiting within the white cube? I argue the answer is yes.

But what is at stake in proving O’Doherty wrong? For me, it is the risk of writing off the important work done by curators, artists, academics, and the like, in dismantling art historical narratives that uphold hegemonic whiteness from within the discipline. I will align my writing with the decolonial project to prod at the Eurocentrism of the white cube as it is embraced by the ‘modern’ museum. Museums, which are western constructs, are institutions rooted in coloniality, Eurocentrism, and racial othering—all of which are interlinked.

O’Doherty’s analysis of the white cube falls short of offering a plan of action in decoding what themes of whiteness and purity mean, particularly as they relate to the raced conceptions of the exhibitionary practice and ideas of modernism. In White, film theorist and author Richard Dyer argues the power dynamics of the Western racial hierarchy are tethered to the notion that it is difficult “to ‘see’ whiteness.” Thus, whiteness is deemed the absence of color, invisible, and subsequently unquestioned as the norm in our visual culture. The inability to detect whiteness as a category is prevalent throughout canonical, institutional art histories, which are often devoid of the non-white “other.” Dyer’s notion that whiteness is ‘invisible’ and difficult to detect (as echoed by O’Doherty) highlights the importance of rendering visible non-white art and visual histories. In occupying space within the institution, Black and brown creators disrupt the systems they have been omitted from rather than conform to them.

Occupying Space will reference the exhibition Grief and Grievance: Art and Mourning in America at the New Museum in New York as its core case study. The show was conceived by the late Nigerian-born curator Okwui Enwezor but was realized by a group of curatorial advisors across varying positionalities and disciplines. The dissertation is organized into three sections following the three core artworks Enwezor regarded as “historical cornerstones,” or “anchors” of the show, which he called upon to guide each floor of the exhibition: Daniel LaRue Johnson’s Freedom Now, Number 1 (1963– 64), Jean-Michel Basquiat’s Procession (1986), and Jack Whitten’s Birmingham (1964).

The show ruminates on the “American epidemic” of normalizing white nationalism, white grievance in the wake of Black grief, and the interconnection between them. Despite their etymological similarities, the terms “grief” and “grievance” are deceptively different: Grief is defined as mourning with intense sorrow, often in response to death. Grievance is an urge to complain in response to (real or imagined) unfair treatment. The exhibition denotes white grievance in response to efforts towards exposing and dismantling systemic racism, such as uplifting Black voices.

I maintain that the environment of the white cube strengthens the show’s message. As the exhibition highlights contradictions within American institutions, it ultimately engages in a critical dialogue with the space it inhabits. This argument is further supported by Bridget R. Cooks’s Exhibiting Blackness, in which the author considers the curatorial methods drawn upon for museum exhibitions of African American art. Cooks writes, “The exhibition of art by non-White artists in art museums is an affront to racial boundaries set to enforce and protect the myth of a racial hierarchy.” This is not to say all art by non-white artists must be ‘political’ in subject matter; however, it is always a political act to exhibit art by non-white artists within institutional spaces. Moreover, repetition of such ‘political acts’ through a breadth of curatorial and artistic voices can successfully subvert the power of the white cube, as seen in this case study.

This is not to say O’Doherty’s argument should be fully rejected. However, we must note that his theory of the white cube hinges on a failure to consider non-white creators’ abilities to subvert the ideology of the space. This oversight is problematic and perpetuates raced narratives of modernity and art history. Additionally, re-imagining the white cube is a short-term solution aiming to address racial and identity-based inequity issues in the visual arts. However, a goal of arts spaces free from systemic barriers necessitates thinking beyond institutions.

—

Anna Ghadar is currently a Candidate for the MSt in History of Art and Visual Culture at the University of Oxford.

Please follow us on Twitter and Instagram (@poltern_) for updates and share our newsletter with anyone who might be interested.