Welcome to the fourth Poltern Newsletter! This week’s issue includes “The Artwork as Promise: Contract Law and the Morality of Paint,” a creative writing piece inspired by a series of forged works sold by M. Knoedler & Co in 2007, written by Henry Woodland; a review of Hilton Als and Glenn Ligon in Conversation at the Princeton University Art Museum, by Anna Ghadar; “The bleak future of post-internet art: NFTs, bitcoin, and blockchain,” a timely feature on the overlap of crypto and the arts by Anastasia Tsaleza; and an interview with Paris-based gallerist and University of Oxford masters student, Alexis de Bernède, by Anna Ghadar.

If you have any questions or comments please do reach out to us by responding to this email or writing us at polternmag@gmail.com.

Thank you for being here.

The Poltern Team

The Artwork as Promise: Contract Law and the Morality of Paint | Creative Writing

by Henry Woodland

Recently I was standing in a gallery looking at a small Gauguin painting with an Italian woman, who told me it moved her deeply. I too liked the Gauguin, though I knew it had been painted by a Lithuanian physics PhD who lived around the corner in Soho: it was ‘fake’. I didn’t want to share this with the Italian, though not because I feared undermining her communion with the artwork—rather, I felt her experience with the painting was no less valid for it being a forgery. The marks on the canvas had excited a feeling that was genuine. Why disrupt it?

The exhibition of a false picture, as explained in the gallery notes, was in response to a series of forgeries which had been sold by the M. Knoedler & Co in New York. Since the 1990s the gallery had dealt works by Kline, de Kooning, Pollock, Rothko, and Motherwell for many millions of dollars, all of them fake. They ended up in private collections, art fairs, and public galleries. Around 2011, the scheme was found out—there was a Netflix documentary, and so on. Even after an FBI investigation, it isn’t clear whether Knoedler had actual knowledge of the fakes. It’s at least true that the directors turned a blind eye to many works of questionable provenance.

Around a decade before Knoelder had purchased their first forgery, the American scholar Charles Fried published his book Contract as Promise, which sought to establish a moral foundation of contract law. Fried posited that contracts, by which individuals voluntarily impose obligations on themselves, are at the heart of individual autonomy. Breaking a contract is like lying, since ‘a liar and a promise breaker each use another person’. In fulfilling a promise, one respects the autonomy of the other party rather than treating them as a means to an end. While Fried’s theory was doctrinal, it ultimately gave weight to the promise as an ethical vehicle: contracts sustain the reciprocity required for human affairs to flourish.

In the Knoedler scandal, formal concerns of art appreciation were contiguous with a series of false promises. The dealers encouraged buyers to engage with the paintings aesthetically, and signed undertakings that held they were authentic. The lawsuits over the works concerned the false bases of those contracts, but they must also have been motivated by a shame at the broken emotional response. What I think the superposition of obligation and attachment here reveals is that art fraud is not a formal exercise, or at least not purely. The work exists in a dialogue between consenting individuals: when A has lied to B about its nature, that false truth is woven into B’s process of aesthetic reception.

Skeptics of modern art use forgeries to argue that the holiness attributed to paintings is all a sham. When a buyer is deceived into spending millions of dollars on a Rothko only to find out it was forged, the cynic argues that all purported connection to art is pretension. Even where a painting is real, the attachment it draws is said to be a product of external mood.

There is no shame in identifying with the cynic: the buyers suing Knoelder were new-world elites, overcome by a practically reptilian desire to possess modern masters. But too crude a version of this analysis risks overlooking the role of trust as a mediator of aesthetic experience. Attachment to a work cannot exist in a vacuum—it rests on a system of cultural and social understandings, formed in part by promises. Concepts of originality and authenticity are necessarily contingent.

If someone wants to exist today they must put a lot of trust in other people, an inherently vulnerable act. The results can be devastating. A buyer does not attach to a work only because its marks affect them in an immanent manner, but because they have agreed to an understanding of what those marks mean: how they were executed, who executed them, how they have been received. A seller conditions this response through a series of promises. Sometimes, they use the human buyer like a tool or a piece of furniture. After such knowledge, what forgiveness?

After we had left the gallery, the Italian and I stayed up late on a balcony in Earl’s Court making promises to one another. She told me she felt deeply about me, which I later found out wasn’t true even at the time. She had the sort of ambiguous, obsidian eyes that Gauguin gave his models while he was dying of syphilis. They’re there in the real ones and the fake. I honestly hadn’t seen anything coming.

—

Henry Woodland is currently an MSt candidate in English at the University of Oxford.

Hilton Als and Glenn Ligon in Conversation at the Princeton University Art Museum | Review

by Anna Ghadar

While on the phone the other day with an old co-worker (hi Shelby, if you’re reading!) she recommended I watch a video of cultural critic, writer, and Princeton’s current Presidential Visiting Scholar, Hilton Als, in conversation with the artist Glenn Ligon. The two discussed various matters, most notably issues of race, identity, and language, with regard to their respective media: written word and visual arts. For the series, Als interviewed Ligon on his practice, however, because writing and visual arts are not mutually exclusive, their intimate discussion of complex issues was dotted with thoughtful nods to literature by Toni Morrison, Fred Moten, and Saidiya Hartman among others. Ligon also reminisced about his childhood in the Bronx in New York City and his mother’s unwavering support, despite not totally understanding what a career-artist “does.”

In a literal overlap of the written word and a studio art practice, the two discussed Ligon’s neon light series. The artist noted that he kind of fell into the medium – a lighting technician (and now, a friend) who’d worked with many New York-based artists encouraged Ligon to dabble in neons, to which he quipped “I don’t do neons.” Shortly thereafter Ligon had a lightbulb moment after discussing the practice of painting commercial white neon bulbs black to achieve a “black glow” in response to the inability to produce black neon, given blackness is the absence of light. With that, Warm Broad Glow (2005), a 22-foot-long neon sign that reads “negro sunshine,” was born. Ligon pulled the name from Gertrude Stein’s “Three Lives,” which follows three young women—one of whom is Melanctha, a bi-racial Black woman—in the early 20th century. The line he references reads “Rose laughed when she was happy, but she had not the wide, abandoned laughter that makes the warm broad glow of negro sunshine.” Stein’s repeated use of the phrase—with its dated language and suggestion of “acceptable” Blackness; always presenting oneself with a “sunny” disposition—is disturbing. Ligon and Als peel back the layers of Stein’s repeated use of othering as a literary device in their discussion of the piece. Why did Stein choose to work through this text about complexities of identity and desire through a bi-racial woman when she, herself, is not? Why did did the author choose this language? And what do her phrases and descriptors signify today? Of course, there’s no one answer, but their deconstructive approach to Stein’s writing provides some insight into Ligon’s use of text in his work.

This concept of “negro sunshine” led to a discussion of conditional acceptance of Blackness, and the demonization of Black upset and grief. Ligon also spoke on other projects, both curatorial and studio-based; However, his introduction of Grief and Grievance: Art and Mourning in America, which is currently on view at the New Museum in New York, really piqued my interest. As a curatorial advisor for the show, originally conceived by the late curator Okwui Enwezor, Ligon underscores the exhibition’s ability to convey both the import of political action and the catharsis which occurs in grappling with such complicated emotions through art. Grief and Grievance spans all three levels of the New Museum’s galleries with works by 37 artists from the 1960s (in line with the American civil rights movement) to today. The works on view, most of which were selected by Enwezor, are emblematic of what the late curator beautifully expressed as “the concept of mourning as a complex political act.” The show ruminates on the American epidemic of studied white grievance and normalization of white nationalism in the wake of Black grief as a response to sustained racial violence against Black people and people of color. The terms sound remarkably similar but are deceptively different—the first is defined as an urge to complain in response to (real or imagined) unfair treatment, the latter is to mourn with intense sorrow, often in response to death.

Ligon’s neon A Small Band (2015), which reads “blues blood bruise,” is positioned across the museum’s façade on the Bowery. The words are pulled from the testimony of Daniel Hamm, who was a teenager when he was beaten by police for pocketing fallen produce and later accused of murder with a group of boys known as the Harlem Six. In his testimony, Hamm stumbled over the words blue and blood: “I had to open the bruise up and let some of the blues/blood come out to show them.” A Small Band was also featured at the entrance of the 2015 Venice Biennale, curated by Enwezor, and the 2017 exhibition Blue Black at the Pulitzer Arts Foundation in St. Louis, Missouri, which Ligon curated.

During the Q&A, a few questions using ill-fitting or questionable terms cropped up. In these instances, Als and Ligon dissected the choice of phrase, par for the course with their linguistic approach to art historical analysis. A favorite line of mine was something Ligon said in response to one of these questions, something to the effect of “when I say folx, I mean Black folx.” As in, this is work by and for the Black community in all its limitless iterations and experiences—it’s not meant to consider the white gaze. The audience member had asked him to discuss how he deals with exhibiting Black grief for white audiences. The simple answer is, he doesn’t.

—

Anna Ghadar is currently a Candidate for the MSt in History of Art and Visual Culture at the University of Oxford.

The bleak future of post-internet art: NFTs, bitcoin, and blockchain | Feature

by Anastasia Tsaleza

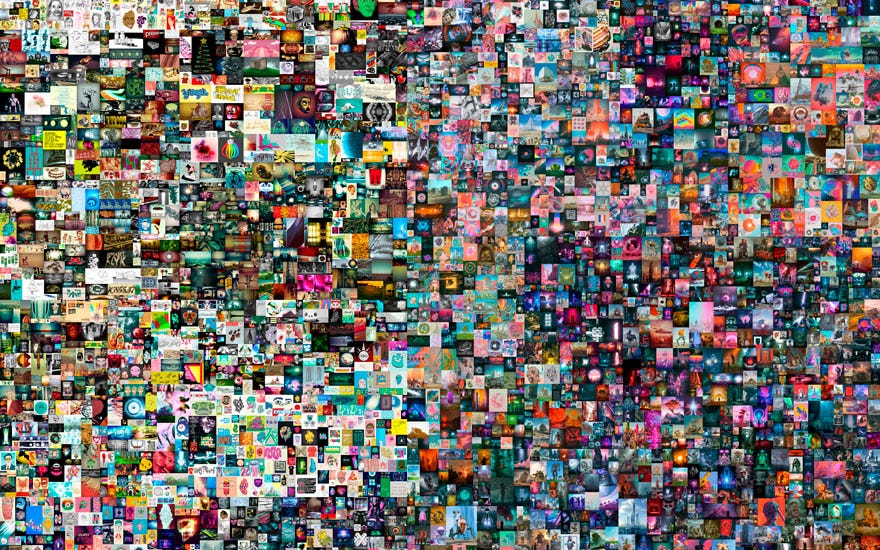

The GameStop stock fiasco and the skyrocketing of dogecoin have taken place within the span of a few months during the first half of 2021, with worldwide consequences. To add to the confusion, news about art auctions, no matter how monumental, rarely make it beyond art world circles. However, a Christie’s sale (which took place on March 11) changed that, making global news, becoming the first auction house to sell a completely digital artwork, Beeple’s (b. 1981) EVERYDAYS: THE FIRST 5,000 DAYS, for $69,346,250.

According to The New York Times’, this renders Beeple the third most expensive living artist following Jeff Koons and David Hockney. The recent deluge of articles published on crypto-art—alternatively referred to as NFT art—has caused an oversaturation of information that can feel off-putting. While studying art history, we become so immersed in the past (it is the study of history, after all) that we neglect the importance of navigating the increasingly chaotic present.

NFT stands for non-fungible token, meaning that each NFT is unique, ‘inscribed’ with a serial number. NFTs are purchasable through cryptocurrency like bitcoin, the value of which has skyrocketed in the past few months (1 bitcoin = 41,124,52 pounds, as of May 2). Cryptocurrency is not regulated by banks and it exists only in the digital realm. The computer’s most beloved function, the CTRL+C button, cannot be used to pirate an NFT because, as it turns out, there are rules that govern buying and selling, even on the internet. NFTs offer a way to copyright a unique product of intellectual property through blockchain, which protects the NFT from being duplicated, maintaining its uniqueness.

While the artwork’s content has already been extensively critiqued (Ben Davis’ breakdown of Beeple’s ‘magnum opus’ is brilliant), it is worth investigating this process’s novelty. As art market pundit Georgina Adam broke it down in The Art Newspaper, purchasing NFT art becomes inscribed into the work’s blockchain (akin to a genetic code), a permanent record of purchase which proves ownership and protects the artist. In December 2020 alone, she writes, almost $9,000,000 worth of NFT art was sold. Of course, digital art is not new, and neither are NFTs; the first NFT artwork is credited to Kevin McCoy’s 2014 Quantum. What is new is that the ideas we hold about traditional transactions—giving something in exchange for receiving something—are shifting along with the digitization of the entire artistic process. In the words of NFT collectors themselves, “beyond the stunts, NFTs are creating a new digital value system.”

This leads to the question of whether this digital takeover would have happened if it were not for the worldwide shutdown of museums and galleries. The likeliest answer is that it would have happened sooner or later, but perhaps COVID-19’s impact on the art world was that it accelerated the urgency for the existence of an exclusively digital, non-physical space for artworks, artists, and art collectors. Although the gradual digitization of everything is to be expected, we are getting there far sooner and faster than anyone could have predicted.

As Sophie Haigney writes for the New York Times, “buying an NFT is not so much about buying something, as it is buying the concept of owning a thing—which feels like the logical endpoint of a society obsessed with property rights, finding new ways to buy and sell almost anything”. There is nothing that more succinctly describes the post-capitalist moment we are in now than our current obsession with NFTs. Crypto-art is aimed at the very tech-savvy and extremely wealthy few and, yet, we all want to be involved.

Platforms like Ethereum and Rarible do away with traditional currency, facilitating the purchase of encrypted digital art by cutting out the middleman—auction houses, galleries—maintaining a system that is supposed to be more accessible. However, this touted accessibility might be a façade. The discrimination people may experience during regular financial exchanges is eliminated in digital transactions – and yet, even the most acquainted with technology have trouble understanding the crypto-system’s inner workings. Investing in NFTs is also incredibly expensive, with a target group (presumably the younger generations, like Millennials, or Gen Z) unable to afford such purchases, given the rise of unemployment rates and current minimum wage debates, among other factors.

While watching all of this unfold, my unease increases. In the context of an ongoing pandemic, during which people have lost their livelihoods, or worse, their lives, it feels especially sinister—dystopian even—to read about the millions spent on the idea of ownership. But, then again, buying art has always been an aristocratic sport. The final bidder for Beeple’s Everydays states, “the point was to show Indians and people of colour that they too can be patrons, that crypto is an equalizing power between the West and the rest, and that the Global South is rising”. While undoubtedly true that marginalized groups like immigrants and people of color have been historically excluded from elitist, white-dominated systems—the art world being one example—we should be cautious about whether this is a laudable e precedent, given that, as of now, NFTs might be creating more problems than they are solving.

NFT art is not the most ecologically conscious. There may be no physical, tangible artwork produced, but that does not mean that resources are not wasted. The energy drained to produce and sell an NFT is massive; so much so that, as a reaction, an ecological manifesto for crypto-art has already been published. There have been talks of developing more eco-friendly solutions via an alternative system of identification, to be called Ethereum 2.0, but the timeline for its completion remains murky.

In an interview, artist Seth Price declares that “it makes perfect sense that every 24-year-old should have a trading app on their phone. It goes toward a Silicon Valley libertarian ideal, which is that everybody becomes an investor”. It is crucial to reiterate that, unfortunate as it may be, not everyone can become an investor (least of all 24-year-olds), because not everyone can afford to, and, even if they could, not everyone has access to the same technologies. Technology, as a human creation, is exclusionary and imperfect, and digital poverty remains extant.

Amusing as it might be to watch the NFT boom unfold, pondering over the repercussions of such a shift is unavoidable; not just from an ecological standpoint, but also as museums are emerging more depleted than ever post-pandemic. How will this interest in crypto-art translate into BFA programs and art historical studies? Is this a short-term fix for a world deprived of art, or is there permanent change underway? There is only one way to find out.

—

Anastasia Tsaleza is currently a candidate for the MLitt in Art History at the University of Saint Andrews.

Interview with gallerist Alexis de Bernède | May 11, 2021

by Anna Ghadar

Alexis de Bernède is a founder of the Paris-based art gallery, Darmo Art, and is currently an MSt candidate in the History of Art and Visual Culture at the University of Oxford. He aims to help give exposure to young artists who struggle to exhibit their work, find representation, and connect with collectors. He also aims to make the field as a whole more accessible to young artists, collectors, and art-lovers alike.

Anna Ghadar: Hi Alexis! How are you?

Alexis de Bernède: I’m well, working on our dissertation and an upcoming exhibition.

AG: I can’t imagine doing this program while working full-time. It’s impressive. And running your own business at that. You started Darmo Art in your second year of undergrad, right?

AB: Yes, we—my partner, Marius Jacob-Gismondi and I—established Darmo Art in 2017 at 19 years old. We’ve both always been passionate about art, but for Marius, art is a family affair. He was born into a family of antique dealers and assumed the role well. He also harbored the ambition to bring value to the contemporary art scene. He always tells his family, "every historical artist was once contemporary. I feel like it's part of my duty as a young dealer to be involved in the emerging art scene." He’s currently pursuing a double degree in law and art history at the Université Paris-Saclay and the Ecole du Louvre.

AG: How did you realize at such a young age that you wanted to go into the arts? And start a business?

AB: I first realized my passion for the arts in my mid-teens, after visiting The European Fine Art Fair (TEFAF), an amazing art fair, in Maastricht [in the Netherlands]. I grew up between Paris and Boston, then studied International Management at Warwick Business School in the UK. I’m currently pursuing a Master’s in art history at Oxford University. Between my degrees, I feel I’ve found a footing to develop both my business and art historical interests. I also lived for some time in New York and Hong Kong and gained some professional experience at TEFAF, Fondation Custodia, Galerie Kugel, and Christie's.

AG: So cool. Have you found that living in so many places has impacted the way you view or exhibit art?

AB: I learned a lot from collectors and feel lucky to have seen art in many well-known institutions, like MoMA, the Louvre, or the Tate. It taught me to ‘train’ the eye to what the trends are in each location. I know these are all western institutions, which have their problems and colonial undertones, of course, but it’s useful to see what the canon is comprised of and understand the ways in which institutions aren’t accessible to figure out how to change them.

AG: Can you speak a bit more about western institutions? Or the ‘trends’ across various locales?

AB: While at Christie’s in Hong Kong during the auction season, I was able to see thousands of artworks over a couple of months. For example, 10,000 lots went on sale in just ten days. These lots ranged across all mediums and prices and came from various times and regions of the world. The collections varied from Chinese calligraphy to southeast Asian jeweled objects, to contemporary works from all over the world. These gave insights into the vastness of work available, all ranging in historical perspectives, and artist identities. It was really interesting to see and expand my art historical knowledge around this range of works. Speaking with people from various cultural backgrounds also demonstrated to me the breadth of perspectives that are involved in the viewing and comprehension of art.

AG: Did this ah-ha moment regarding the breadth in artistic practices and the arts more broadly impact your vision for Darmo?

AB: We’re trying to have people from all backgrounds visit our shows and feel welcome. Our model brings people to locations where they wouldn’t normally go by themselves or might feel intimidated to go into. For our show at Ferragamo, for example, we brought in young artists and visitors and wanted to make the space feel approachable. We are making the art world more accessible by connecting artists and art lovers of all backgrounds, by repurposing spaces outside the typical white cube gallery. We want artists and viewers to have fun and not feel pressure to conform to the institutional model of the art world.

AG: Can you give some other examples of how you worked outside the institutional model? Do you represent artists, or do you take more of a casual approach?

AB: We do represent artists, but usually the representation is not exclusive. One of our artists, Raf Reyes, is self-taught and started as a digital artist. We worked with him to develop his first 3D printed works and to elbow his way into the art world, to find his first collectors and patrons. He’s found his own way without formal training, which is really cool to see. With the exposure he gained at his first shows with us, he applied to the RCA [Royal College of Art] in London and got accepted into a Master’s program, without having had any prior formal art training. We’re also interested in interdisciplinary approaches. Our artist Oussama Garti is an architect who’s actively involved in the Moroccan art scene. Oussama works methodically (perhaps relating to his architectural background?), in series of paintings. He starts from an idea, a concept, a tension, or a color, and develops it over 5, 10, or even more canvases to explore all its intricacies. His work is fascinating. We’re excited to be working with him in France. He created an initiative called Interval to promote contemporary Moroccan artists on an international level.

AG: So, you seem to highlight fairly green artists and collectors. In a field that can sometimes feel gatekeep-y, how do you make younger artists and visitors feel comfortable?

AB: I realize the art world and collecting feels inaccessible, but I purchased my first editioned print at auction with my babysitting money when I was 16. I’m so grateful to have had this experience, and I want to show other people that if you love art but don’t have a lot of money to collect, you can still build a collection. Our youngest collector was 18 when she purchased her first work from us. She found an artist that really spoke to her, which is all we can hope for.

AG: Most of your shows have been with fairly young ‘up-and-coming’ artists, which I’m sure makes it more financially accessible, too. Your upcoming show features some huge names—how do you make those accessible?

AB: Now we’re doing our first show with ‘blue-chip’ artists from the 19th and 20th centuries, Meeting the moderns, which will travel between Paris and Antibes [in the south of France]. The exhibition features artists who lived between Paris and the French Riviera, such as Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Paul Gauguin, Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque, Henri Matisse, Joan Miró, Marc Chagall, Antoni Clavé, Arman, and César. The price ranges from 2,000 to 2 million euros with our positioning being that we want established collectors to add historical works to their collection and to have young collectors be able to access historical works for lower prices, in the form of prints.

AG: And when will it be in both locations?

AB: It’s on view in Paris from June 24-July 4 in a traditional artist studio in Montparnasse, in a building where Picasso had a studio, actually. Then it will travel to Antibes from July 7-15, where we’ll set it up in a historical property in the French Rivera called la Bastide du Roy. We’re excited to show in these beautiful intimate spaces that speak to the lives of the artists exhibited.

AG: Sounds beautiful, I really want to make it over there before it closes. Do you have any favorite pieces in the show?

AB: All of the works go so well together. One piece that’s very interesting is a unique blue-glazed ceramic egg by [Joan] Miró and [Josep Llorens] Artigas, which is part of the ‘New Lands’ series created by the two artists in 1956. Their friendship dates back to the 1920s when Artigas lent Miró his studio on rue Blomet in Paris. Stylistically, the piece is related to traditional Catalan painting, where the motif of the egg and the oval is regularly referenced. The oval symbolizes the universal matrix of the ‘split shell’ from which life springs – as if all the secrets of the universe are inside this egg. It’s magical.

AG: Will both iterations of the show have the same checklist, or will you swap out any works? I’m wondering if I should take a long Eurostar trip to see both…

AB: The later show, in Antibes, will feature a monumental travertine centaur by César. The artist and sculptor lived [in the Bastide du Roy] for four years alongside the antique dealer Jean Gismondi, who commissioned Le Centaure. Many iconic artistic figures have visited and stayed at the Bastide over its history, including Francis Poulenc, Jean Cocteau, Colette, and François Mauriac. We’re hoping to highlight the artistic soul of the place by sharing the exhibition in both the gardens and the interior of the Bastide.

AG: Do you have any other projects coming up that you’re excited about?

AB: We’re currently working with Aurèce Vettier, an artist collective founded by Paul Mouginot and Anis Gandoura, that considers how technology can be used in art in meaningful ways. They consider how interactions with machines and algorithms can be shaped through an artistic lens, and vice versa. They’re also playing with using AI to generate art. It’s a true collaboration between humans and machines. It’s really innovative.

AG: You know, I watched a video of this woman who trained an AI to generate images of nudes and it created these random shapes that didn’t even look like human forms. When she went to upload her video online it was flagged for containing nudity. The AI had produced something it believed to be inappropriate and hence a similar social media AI blocked it from being posted, but really it was just an abstract mix of neutral tones. Weird but interesting.

AB: Aurèce Vettier has been working on this project where they’re taking photos of hundreds of flower bouquets in these beautiful antique vases. They then give the images to the AI and have them generate completely new types of flowers. [The AI] comes up with these dreamy arrangements where they have petals and leaves in the right places but some things the computer doesn’t understand. Impossible flowers and unreal branches appear. It also plays with the background and integrates part of the environment within the color and composition of the flower. It’s very cool.

AG: I love it. I want to see this series. Do you have a forthcoming exhibition with them as well?

AB: Yes, but we haven’t confirmed dates or anything yet. We’ll finish Meeting the Moderns first!

—

“Meeting the Moderns,” by Darmo Art will be on view from June 24-July 4 in Paris and July 7-July 15 in Antibes.

For more on Alexis’s work at Darmo Art please visit their website and Instagram (@darmo.art).

Please follow us on Twitter and Instagram (@poltern_) for updates and share our newsletter with anyone who might be interested.