Welcome to the third Poltern Newsletter! This week’s issue includes “Letting objects play,” a contribution to and review of the online platform Things that Talk, by Manuela Gressani; “Trauma in Blue: The Confessional Art of Louise Bourgeois and Tracey Emin,” a reflective feature by Kate McBride; “Looking up at the Stars,” a creative writing piece on the dreamlike qualities of works by Amy Friend, Van Gogh, and Kiki Smith, written by Eva Tain; and an interview with NYC-based artist, Paul-Sebastian Japaz, by Anna Ghadar.

If you have any questions or comments please do reach out to us by responding to this email or writing us at polternmag@gmail.com.

Thank you for being here.

The Poltern Team

Letting objects play: a contribution to and review of Things That Talk.

by Manuela Gressani

When you hear ‘art history’, the first thing you might picture in your mind is painting. Painting, sculpture, architecture, and maybe drawings and prints. You definitely wouldn’t initially imagine little everyday objects, features of routinely, mundane life. Admittedly, our understanding of ‘art’ has long exceeded the mere categories of painting, sculpture, and architecture, expanding in every direction and challenging every canonical assumption. I like to think that my own work (I’m currently looking at Persian doors) in its own tiny way, furthers these efforts; and yet, when we were pitched a contribution to the Things That Talk online platform, I found myself scrambling to answer the core questions this project asks: what stories can objects tell us? How do they tell us? How can we listen?

Things That Talk, born out of Leiden University, aims to create an “interconnected world of things”, one in which objects become the subjects that mediate, record, and unite human experience. It encourages contributors to push past traditional scholarship and really give a voice to objects and their stories. A Swahili Kanga appears alongside a Chinese-Indonesian restaurant in The Netherlands, a French wig-holder, and an MC Hammer doll; each tells its story, and each story interweaves into a rich tapestry of human narratives.

A little elephant-shaped Indian chess piece made between the 17th and 18th century acted as our research contribution to Things That Talk. is extremely cute (I am not at all ashamed to admit how much of a decisive factor this was in our decision-making process), and it gave us a chance to really delve into the convoluted history of the game. Originating in India and consolidating a lot of its modern-day western rules in the Persianate world already by the 7th century, chess attests to military history, diplomatic relations, and trans-Asian exchange. The elephant chess set connected us further to game theory, different archetypes of kingship, the emergence of social leisure, and linguistic developments that led to words like ‘checkmate’ and ‘rook’. With a little practice and a very patient opponent, I think I could even work my way through a beginner’s game of xiangqi, the version of chess played in China.

It is only now, as we are drafting our submission, that I’m fully realizing how much our chess piece had to say. Research usually feels like pulling on a string and following it to its end; this time around, it still felt like I was pulling on a string, but it wasn’t really a string - it was a spiderweb, countless threads branching off in every direction. Coincidentally, HIAA (Historians of Islamic Art Association) recent symposium touched on similar themes of communication and networks. One of the panels focused on communicating art history, discussing the strategies that are at our disposal in museum environments as well as in didactic situations. One of the speakers, Stephanie Mulder from the University of Texas, Austin, eloquently and emphatically talked about the importance of public-facing art history. She stressed open-access resources, wider dialogues, and, perhaps most importantly, an audience-centered tone and language, a way of writing that does not hinge on academic jargon. It was hard to not draw parallels between what she was saying and what I was experiencing as I tried to give a voice to our chess piece. Not only does Things That Talk endeavor to crack a new way of ‘doing’ art history, but it upholds the unwavering conviction that art objects, in fact, all objects speak equally to everyone.

Letting an object speak, I am learning, means retracing its steps, following it from ideation to creation, exchange, use, and many instances of salvaging and recycling. We can listen only if we make a conscious effort to remain flexible, curious, and playful. Dutch cultural historian Johan Huizinga, writing in the first half of the 19th century, conceptualized games not as a fruit of culture, but as its basis. Through play, we lay the foundations for interacting with those around us, and the human dynamics we experience give way to culture. This aligns (un)surprisingly seamlessly with the stories our elephant chess piece is ready to tell us; and yet, I am convinced it applies to far more than that. Perhaps, a healthy dose of curiosity and playfulness is just what art history needs.

—

Manuela Gressani is currently a Master’s Candidate at The Courtauld Institute of Art.

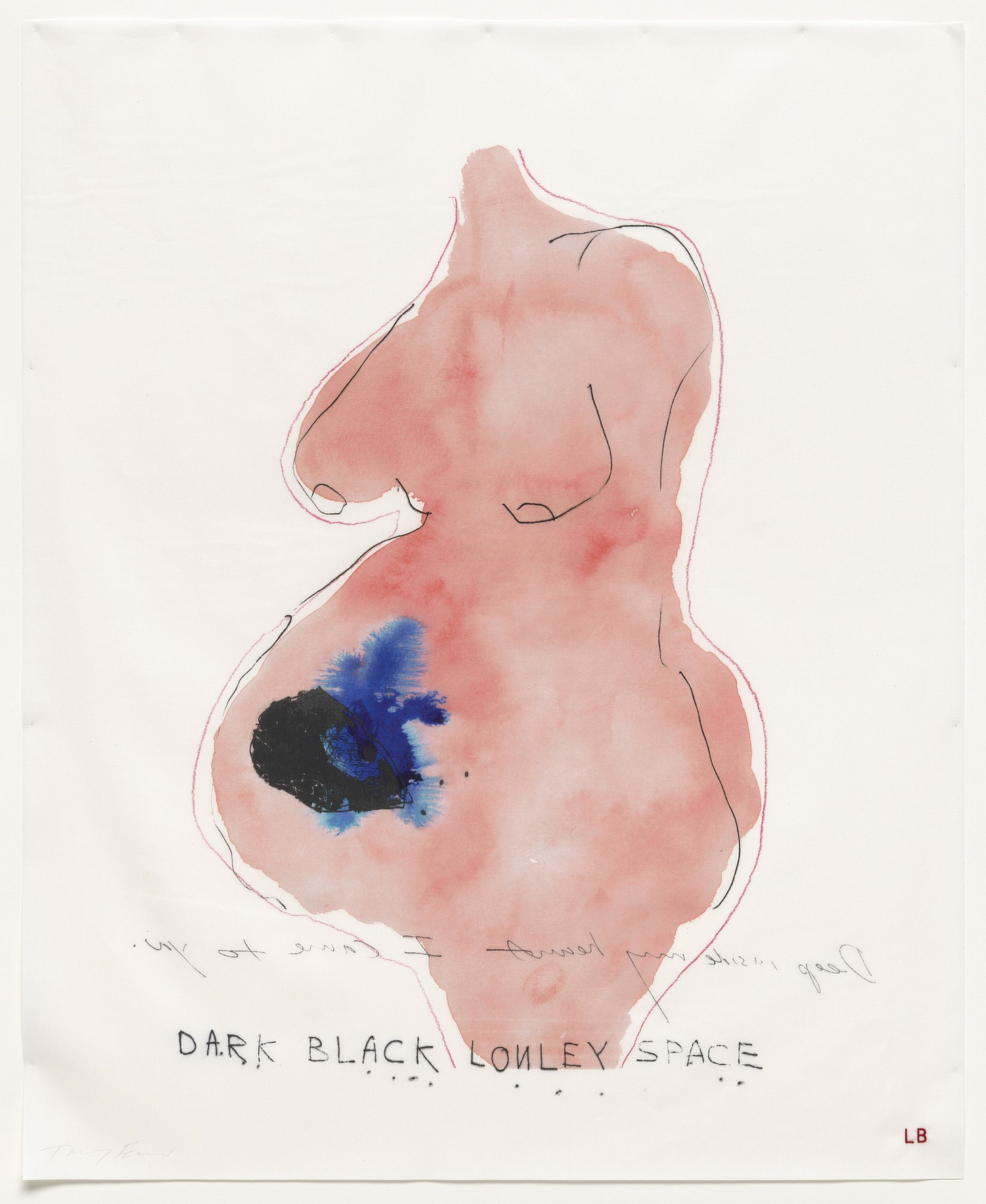

Excerpt— “Trauma in Blue: The Confessional Art of Louise Bourgeois and Tracey Emin” | Feature

by Kate McBride

Within the framework of misogyny, melancholy, and mental health — historically the domain of the masculine majority — it is necessary to examine the way that contemporary female artists eschew expectations with blue tinged deep dives into their own painful minds. No longer relegated to ‘hysteria, hypochondria, and neurasthenia,’ or in further rejection of these problematic histories, Bourgeois and Emin push color and representation to extremes.[1] No subject, no injury, no narrative is off-limits.

The feeling of blue is everywhere. It stretches beyond time and place, through geographical boundaries, from the verbal to the visual, from the religious to the depressive, the biological, the infinite, the art historical. Once you start thinking about blue it surrounds you. It’s written about exhaustively. It is metaphysical, symbolic, divine, but it is also quotidian; a color you couldn’t choose to avoid in your daily life. At the axis of the mundane and the magical, blue is abundant in meaning. Color is temporal and perception is a process not a finite reality. In this way, color makes space to interact with our subconscious. Our eyes collect and apply cues about ambient light and texture to create our vision of the world, turning a scientific process into a philosophical debate, ripe for interpretation from an art historical perspective.[2]

We can trace blue through the lens of physics, place, geology, capitalism, colonialism, culture, creativity, linguistics, religion, and, while these pathways provide poignant stories, we will still never get a clear answer of what it means. As William H. Gass says, ‘So a random set of meanings has softly gathered around the word the way lint collects. The mind does that.’[3] Or as Maggie Nelson describes, ‘You might want to dilute it and swim in it, you might want to rouge your nipples with it, you might want to paint a virgin’s robe with it. But still you wouldn’t be accessing the blue of it. Not exactly.’[4] What we can say only is that it holds significance, it makes us feel.

Overwhelmingly, blues are a ubiquitous reference to sorrow, laden with moodiness, solitude, memory. As Carol Mavor says, ‘…like the sea and the sky, like the gloomy contentment of a melancholic, the nostalgic who is joyful-sad.’[5] Historically this powerful signifier has been used by male artists to express their angst and – in conjunction with the rise of psychoanalysis and the burgeoning conversation on mental wellness that was in practice only a man’s purview – dive into the depths of blue to explore and express their inner worlds. From a semiotic and feminist lens, it is less important to focus on the rules and roots of blue, but instead to center on what it suggests.

Color has shaped art history and played a crucial role in its progression, from the possibilities created by pigments to academic debates on color’s place in artistic hierarchy, to the impact of language surrounding perception itself.[6][7] When the subject of the art historical blue is suggested, the same handful of references arise. Giotto’s bright blue swept chapel, the Virgin Mary’s royal blue robes, Picasso’s mourning period, the color of Joan Miro’s dreams, Yves Klein’s dedication to a hue. In the early twentieth century, blue allowed men to express their feelings: the color became a code of representation through the lens of the masculine gaze on the world. Color theory becomes more psychological than material as we move towards modern and contemporary moments, blue is utilized to convey depressions and anxieties.

The use of blue in the contemporary confessional model by female-identifying artists is a symbolic seizing back of art historical and psychological discourse, both of which have historically made little room for feminine perspectives and contributions. As Gass explores this subject he explains, ‘Blue is therefore most suitable as the color of interior life. Whether slick light sharp high bright thin quick sour new and cool or low deep sweet thick dark soft slow smooth heavy old and warm; blue moves easily among all, and all profoundly qualify our states of feeling.’[8] Neither Bourgeois nor Emin deal solely with blue, but when they do, they reclaim the color, pairing anguish with endurance. The representation of trauma in this manner is an actionable demonstration of agency; a rejection of the masculinization of the canon and the misogyny of mental health.

Please click here to read the full article.

—

Kate McBride is currently an MLitt Candidate at the University of St Andrews.

[1] Topp and Blackshaw ‘Scrutinised bodies and lunatic utopias,’ p.18. [2] St Clair, The Secret Lives of Colour, pp.13-15 [3] Gass, On Being Blue, p. 7. [4] Nelson, Bluets, p. 4 [5] Mavor, Blue Mythologies, p.20. [6] Lichtenstein, The Eloquence of Color, p.147. [7] St Clair, The Secret Lives of Colour, p. 35 [8] Gass, On Being Blue, p. 75.

“Looking up at the Stars” | Creative Writing

by Eva Tain

The boredom, loneliness, and uncertainty brought on by the pandemic have affected people’s mental health, which, in my case, translated into insomnia. Unable to shut off my brain, I would be wide awake in the middle of the night. I would then sit up, absent mindlessly stare out the foggy window, and look at the sky. At times, it was pitch black. But, other times, it was full of stars.

Just like I looked up at the stars through my student accommodation’s window in the sleepless night, Vincent van Gogh looked up at the stars through the Saint-Paul Asylum’s window to paint The Starry Night in 1889, which became one of the most recognized paintings in the world. Van Gogh wrote about the painting, in a letter addressed to his brother Theo, “I saw the countryside from my window a long time before sunrise, with nothing but the morning star, which looked very big.”

While visiting the Museum of Modern Art in New York, I was only able to take a quick glance at The Starry Night. It was nearly impossible to approach it because the room was overcrowded. Nonetheless, I had another chance to see the iconic painting at an immersive exhibition dedicated to Van Gogh at L’Atelier des Lumières in Paris. I do not know how long I stayed in this room filled with music, water, projector lights, and digitized moving paintings. What I do know is that I found peace in these dancing stars flirting with the wavy sky.

The Starry Night’s unrealistic and swirling night sky is often considered to be the result of Van Gogh’s madness. Such a narrative comforts the myth of the tortured artist, which is both caricatural and reductive, especially when Van Gogh himself explained that he purposely painted flowing lines and chose to use short brushstrokes and rich colors. In his eyes, The Starry Night is a love letter to the beauty of the night that he finds “much more alive and richly colored than the day.” Indeed, when I look at Van Gogh’s painting, I am mesmerized by its beauty.

I was once asked if I thought that beauty could save the world, to which I answered “yes.” Perhaps my response demands a level of privilege, seeing that beauty does not act. But I wonder if it can compel it. Surely the world does not become a better place when I get lost in the beauty of a night full of stars. However, to me, the beauty of a starry night instills hope that the world can be a better place. Maybe beauty does not act. But it can give us the strength to act.

Contemporary artist Kiki Smith, whose art is described as feminist, plays around with the idea of beauty in her work. She is quite fond of stars, and even has them tattooed on her arms and legs: “these used to be stars, but now they’re dots,” she explains when asked about the blue dots on her skin. Her tattoos are a reference to Nut, an Egyptian sky goddess, whose body is often represented as blue and covered with stars. At the exhibition at La Monnaie de Paris dedicated to Kiki Smith’s work, I encountered, in between sculptures of women being crucified and burned at the stake, artworks that wandered off in the world of fairytales, mythology, and cosmology. Her tapestry titled Sky depicts a woman floating in a starry sky, which brought me both poetry and harmony. It felt like a breath of fresh air, a welcome break from surrounding violent images. In a world full of injustice, brutality, and anxiety, appreciating beauty from time to time does not hurt. Taking a second to contemplate the stars can help me have a clearer mind and see things differently.

Amy Friend’s Dare alla Luce series illustrates this idea of channeling beauty to look at things with a different perspective. Friend pricked holes into vintage photographs and let the light shine through, making it seem like they are covered in stars. In doing so, she gave the photographs a new life. When my friend introduced me to Dare alla Luce, I was first drawn to the aesthetics of these sparkly vintage photographs. They express a sort of calm and nostalgic beauty that is both haunting and comforting, as paradoxical as it might sound. Something about the atmosphere of these photographs reminds me of a late-night lullaby. But the more I stare at them, the more I am able to see them for what they are: images that are, as put by Friend, “permanently altered,” for they are both “lost and reborn.” She declares that they “comment on the fragile quality of the photographic object but also on the fragility of our lives, our history. All are lost so easily.”

When I look at these shiny pictures, I start wondering about their past lives. Who is this unknown woman in the lake? The light dots surrounding her make her look like a ghost. Is she dead? If so, how did she die? How long did she live? Who was she when she was alive? What is her story? Aline Smithson eloquently writes that the photographs of Dare alla Luce are “[transformed] into glowing memories or poems of stardust and shimmer that allow our imaginations to wander.” Poems of stardust. I like how that sounds.

“We are all in the gutter, but some of us are looking up at the stars.” These words, written by Oscar Wilde in Lady Windermere’s Fan (1892), have stuck with me for the past few years. I often find myself stopping in the middle of the street to look up at the stars during late-evening walks. In museums and art galleries, I linger a little bit longer on artworks that depict stars. Do I have a voice, or am I nothing but a speck of dust? Perhaps there is no point in asking the stars for answers. Perhaps I should better take action to change the world I live in, instead of being distracted by beauty and wondering what is beyond. Yet, the thought and the hope it inspires are what keeps me going. So, I will turn off the light tonight. I will open my curtains. And, from my cozy gutter, I will once again look up at the stars.

—

Eva Tain is currently a Candidate for the MSt in History of Art and Visual Culture at the University of Oxford.

[1] Barliant, “‘If you can outlive most men, all of a sudden you can be venerated’ – an interview with Kiki Smith.” Apollo Magazine, 26 October 2019. https://www.apollo-magazine.com/kiki-smith-interview/ [2] Smithson, “Amy Friend: Dare alla Luca.” Lenscratch, 30 April 2013. http://lenscratch.com/2013/04/amy-friend-dare-alla-luca/ [3] “Kiki Smith.” Monnaie de Paris. https://www.monnaiedeparis.fr/en/temporary-exhibitions/kiki-smith

Artist Interview with Paul-Sebastian Japaz | 1 April 2021

by Anna Ghadar

Paul-Sebastian Japaz is a painter who currently resides in New York, NY. In 2017, he graduated with a BFA in Fine Art from the Fashion Institute of Technology. Paul uses space to explore the idea that it can influence behaviors in people. Positive Space is a resource, and in many cases, a privilege afforded to those in power. The work considers Queer identity and places it in the context of everyday life through the power of space and environment to define a place of our own.

—

Anna Ghadar: Hi Paul! So nice to see you.

Paul-Sebastian Japaz: Hey, how’re you doing?

AG: Good, I’ve had too much coffee this morning so I’m in a weird mood. But good.

PSJ: Yeah, I mean it’s not a bad mood to be in… what have you been up to?

AG: My exams are coming up – three essays over the course of three days – then I have to write my dissertation over the following 8 weeks.

PSJ: What are you writing on?

(Editor’s note: The irony that Paul is practically interviewing me, here, is not lost on me. He’s just so charismatic and easy to talk to – we spent the first 10 minutes of the call joyfully talking about Apple’s suggested headphone audio levels…)

AG: The limitations of Brian O’Doherty’s Inside the White Cube – a collection of essays he published in the 70s saying the white cube space has all of these “artifying” agents, so when you put something in the space it “becomes art,” but people often don’t engage critically with it and it continues the problematics of the canon. I’m not describing it well, but you get the gist.

PSJ: No, of course. I used to think about context a lot, especially when my work was more abstracted and more form and color-based – although it is still color-based. I used to think about how it was presented, and not to be part of the problem but I do feel like that neutrality is always something that I really went for. But I absolutely hear that. The best way I can put this is when you go to a space that collects historical works, like, say, “natural history,” or The Met, and you’re walking through, say, the Oceanic wing and it’s so big and overwhelming, there are these objects that can really be confused for other things. And because Oceania was so influenced by African art and migration… because a lot of the pieces were so ritualistic based on dance and movement, this culture of performance and taking them out of context feels such a detriment. But also, you go to places like the Natural History Museum and they’re playing rainforest sounds and like, the Bed Bath and Beyond music of the world CD you’re like this is so inappropriate. So, how do you immerse the interested viewer in this kind of world? It doesn’t necessarily mean historical work, but I don’t know it’s a big question – you get into this idea that work itself comes from this individual take and you have to build all of these requirements in order to express your work. Or, in the white cube setting, it’s really democratic – I love standardization – and I love that everyone gets this “thing” and it’s “just good enough” to communicate your point. So maybe use it as a building block. I don’t like seeing work in a studio, like how you’re seeing my work now. I don’t want to see work in somebody’s house either, I want to see it in something very neutral. And if it’s not very neutral then how does the work speak to the environment?

AG: I agree, basically, all contemporary art presupposes the white cube. Note that [O’Doherty] was writing in the 70s so not our “contemporary.” Like, Nauman was his contemporary. You’re creating work assuming you’ll show in a white cube and I think that as long as you can curate the show and engage the viewer in a particular way you can have a critical dialogue with these pieces in this space. It’s not the fault of the architecture necessarily – you want to create a conversation between the artist, the viewer, the curator, and the institution (although “the voice of the institution” is often problematic) and that’s how you have a critical dialogue.

PSJ: I wonder if it’s kind of blame-shifting. Oh, blame the context, the architecture, these things that have to be decided upon first and require some kind of investment and become long-term decisions instead of blaming those who are designed to navigate these situations. It becomes this standard of professionalism and, I don’t want to say mimicry, but mirroring. Who can have these big rooms, and these neutral floors, but what is the alternative?

AG: So, what’s your dream exhibition space?

PSJ: Just back me up into a wall there…

AG: White cube?

PSJ: Well yeah, my work has to do a lot with space. Not the kind of space that you would see in photographs or home catalogs, but more about the idea of the space. If I think about a space – not necessarily in a nostalgic way, but what would this room look like? – want the physical environment to be incredibly neutral. I think of this paradox of a room within a room and I kind of hate that. It’s so stupid to me. So in whatever room, setting, or context that doesn’t make you feel like you’re in a room, I want the narrative to be on the works themselves, separate from the narrative of where they’re being shown. I want the attention myself; I don’t want to give that attention to something else [like the space]. My work is so heavily geared toward color and composition. I consider aspects of framing, how the work is “working,” how will it live when it leaves my studio, and I want that to harmonize within the overall messaging of the work. It’s not reasonable to expect the larger space to perform that way.

AG: You want the viewer to be in the space you’re showing to them?

PSJ: I want them to be aware of what I’m showing to them. I think of this in a very humanistic way – this is going to sound dramatic – but when you go to a great dance show, you’re present and engaged. There’s a kind of trauma that makes you resonate with what you’re looking at. It’s a moment, not an epiphany, but a “woah.” It happens in many media and in many ways, but I would be so lucky to have something like that. And you get those moments by speaking to more humanistic outlets in the viewer. If your work speaks to this subconscious aspect within people, then you can have this resonating ding that happens. That’s what I’m trying to achieve on the front. And I think that's what every artist should. Not just painters or sculptors, anyone creating. It’s hugely tacit. It’s not easy to pin down. I think when it happens it really happens.

AG: You’re trying to evoke that feeling in the viewer to show that you share that emotion.

PSJ: Absolutely, and I don’t like to use the word emotion because it feels very one-sided, but I trust you know what I’m talking about. Not just one emotion but this poetry of this thing that’s happening in front of me and it’s communicating this very specific thing and I’m watching it. There’s a lot of artists that achieve that – and it “dings.” Every artist should strive for that.

AG: Have you seen a show that’s “dinged” recently?

PSJ: No, not recently. I think the last good show I saw – I’m going to bite my tongue in the future saying this – but that Matthew Wong show we saw. Or, that one yellow Morandi painting really does it for me. Absolute harmony. Everything you, or I, want in a painting. That resonating moment with anyone who looks at it. It’s been a bad year for art. A great year for making art, if you’re lucky enough to do that. But a bad one for looking at art and being “a part of art.”

AG: Hopefully we’ll see something good soon.

PSJ: Hopefully, I’m in no rush. I’m really looking forward to the Neel show at the Met and the Mehretu show at the Whitney. But going back to your question on the authorities in art, what does the context of the institution have to say about these – I don’t want to say women painters, but painters? Why is there this optical allyship right now? I’m thrilled Neel and Mehretu are having shows, but what is the actual messaging?

AG: Like, what does it mean to canonize a youngish woman of color in this American Art Museum of the Whitney that has been under so much scrutiny recently?

PSJ: Of course, and I don’t want to take away from her moment, let me be very clear. I’m very happy she has this show and I’m very much looking forward to going to this show. I just want more of the art that comes out of this vein. But, the institution is very much at fault because it’s taken this long.

AG: Yeah, and it doesn’t have to be one or the other, it can be both. But it’s important for the viewer to recognize that there can be ulterior motives behind showing any work. Including in the decision to show canonical straight white male artists’ works, it might not be just that his work is cool, but that it’s driving up the price of his work to have all these monographic shows. There should always be some kind of critical engagement with why these works are exhibited.

PSJ: I don’t want to say that’s the issue I’ve had as I don’t think I’ve always been so consistent about it, but it’s always been my apprehension in seeing shows. Realizing that it’s another Serra show, or whatever. Serra’s great, don’t get me wrong. But it’s very easy to say, if I’m just starting to collect art, that “oh I’ll get a Serra” – maybe not the huge steel things – but the little circle prints because it’s a no-brainer. But I try, in order to save my own attitude, and not be so jaded, to not think about the sale. And I guess that’s a sign of infancy in your career. Like I’m just “making” right now.

AG: I wanted to ask you because your work focuses so much on the interior and the home, how has COVID changed your practice, if at all?

PSJ: This feels insanely privileged of me to say, but I don’t know if I would’ve been brave enough to take that jump. As an artist who doesn’t come from wealth, it’s an insane jump to make. It makes you question, am I doing this right? Should I be doing this? I had a few bits of insecurity even going to art school. That was a question I always had – am I really going to do this? To take this jump? It feels like, who do I think I am trying to play this game, why me? Watching [Ru Paul’s] Drag Race, listening to what Ru says, “you’re your own biggest saboteur” or “if not now, when?” really got me into the mindset. And [during the pandemic] being at home all the time it was the perfect storm, in a good way. I was like, okay I can do this, I can handle this, I have all the time in the world. I learned the signs [to ask myself] what are the signs I’m putting something off? That I’m overwhelmed? That I need to work harder? It’s really helped me focus and hone in. I’ve been really fortunate and I feel I was able to navigate the storm in a way that gave me the tenacity to continue to work.

AG: That’s amazing! That’s good. How do you feel your practice is going to change [after receiving the vaccine and the “end” of the pandemic]?

PSJ: Now that the world’s opening up, it’s finding a balance. How do I say this? As of now, I’m not looking for a day job because I feel this is more important right now. It’s a question of how do I navigate the financial side and the creative side. The next stages are going to be very expensive – going to grad school, getting a bigger studio, these “big-ticket investments” is what I’m calling them – that is going to ultimately help my career. In order to get to that stage, I need to feel like my career and my work are actually going to get me there. At the moment, my biggest goal and also my biggest reward is just to keep working and making the work be the way I want it to be. Making it all feel very sincere and that I’m proud of it. Every artist hears that you have to just focus on the work, can’t have any bothers coming in, and hearing that advice, I used to think that was the most out-of-touch statement anyone could ever make. And it sort of is. But it’s what had to get me there. Now that I’m focusing on painting because of COVID, everything’s coming together.

AG: It’s interesting that you say that, because this kind of pertains to my dissertation – sorry, it’s the only thing I can think about – but, in this theory, I’m discussing the limitations of, O’Doherty says that the white cube is “hermetically sealed,” with no outside sound, light, etc. and it’s this spooky, almost holy, space. He says it’s this negative thing because there are no tethers to the outside world. But, on the creative side, not having outside bothers complicating your process actually helps your practice?

PSJ: It’s interesting because it’s making a larger metaphor and the larger metaphor is not lost on me. Absolutely, you need both. Nobody is an island. And I’ve had a lot of help from my creative community: can you look at this piece for me? And so on. That dialogue is important. So, in that case, I am anti-hermetically sealed. I would never want to be like Bon Iver who goes to the cabin and just works...Get over yourself.

AG: A modern-day Ralph Waldo Emerson.

PSJ: Who do you think you are that your ideas are so pure and cannot be corrupted by the outside world? No! You need a community. You need the people around you who you ultimately will be a part of and leaning on for support. And they’ll be leaning on you. Building everyone up in your community is much more valuable than what that statement was leaning towards. Nobody is an island. This idea of the hermetically sealed anything is very antiquated, it’s very 70s. I think the future of art is social and “the voice of the community.” I don’t want to make grand statements like that because I don’t want to be held accountable if I’m wrong. It’s always been community-based, but the identities of the communities are what’s going to be considered. Like New York during the Abex, that’s The Art World, not just one community. But I think the art world is going to have a lot of satellites, which is great to me. All these artists speaking their voices through their individual ways and practices. As a brown, gay artist I feel that’s my own goal: to build and support these communities and continue to help to thrive in that way.

AG: I fully agree. First, great point. Second, in my opinion, any time there are symbiotic relationships between artists or creators they’re evident in your work. And, not to lean too much on identity politics, but it is important the way people identify.

PSJ: And you can’t get rid of your identity, it’s going to be a part of the work. I can do landscapes, portraits, or “art for art’s sake” or whatever, but my background will always shape the work because I am not white, I am not straight. It’s going to come up.

AG: Your positionality will always paint (no pun intended) the way you view the world. So, what are you working on right now?

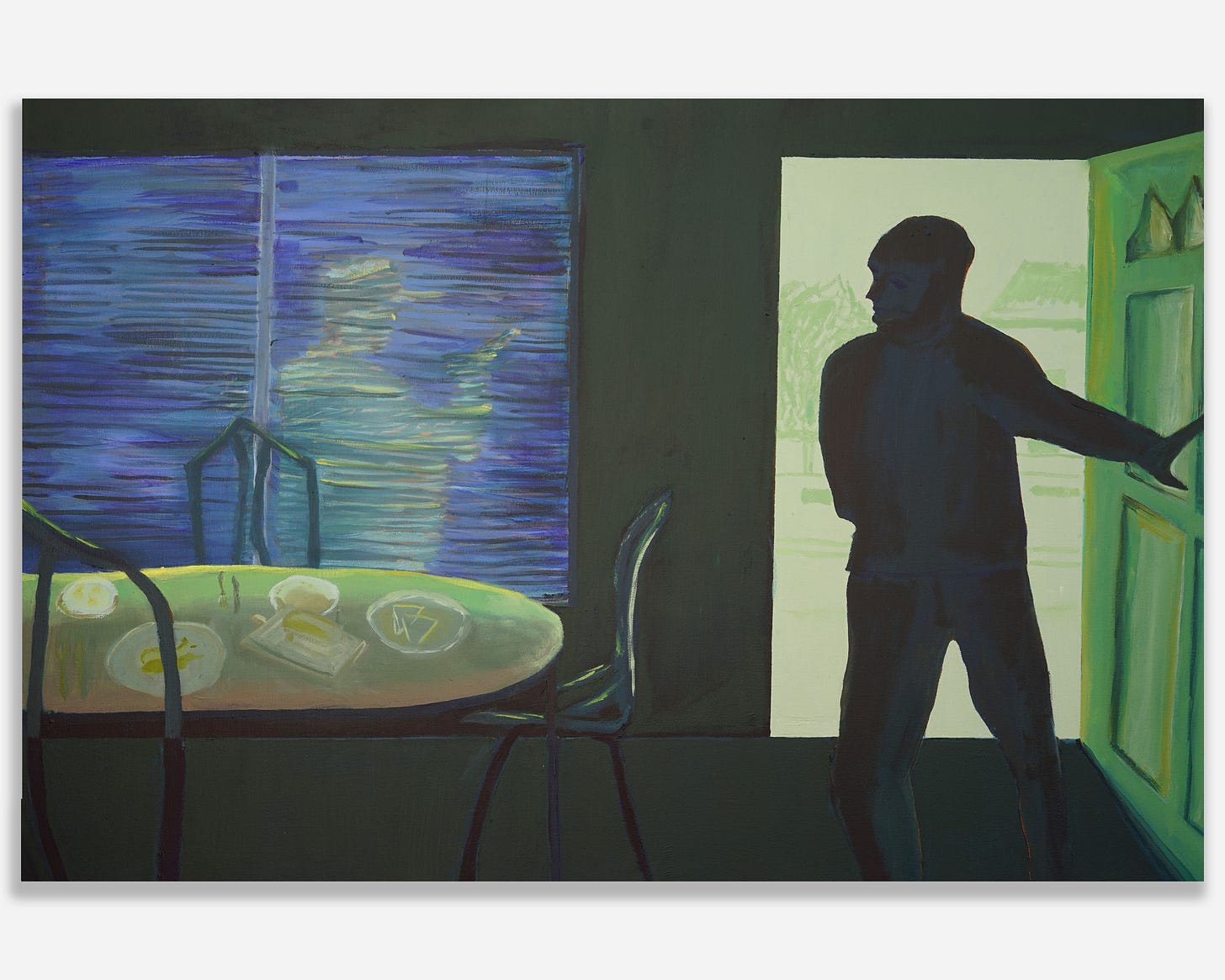

PSJ: *points to a blue work, Late Visit, behind him* This work is drying.

The work is designed to be narrative-based. It’s meant to speak indirectly about what it’s doing. I think about color and composition, obviously – these are the kind of formal things that any artist would think about. But I think the idea of the room is very important because the work is designed to feel like the idea of something, space in theory. It’s a very important aspect of the work because there’s this distance I want to create between the viewer and the work. Imagine you’re walking down the street and look into a person’s room. That is hugely personal and sensitive. It’s theirs. There’s a level of power that comes with that. I want to put a pin in that power because it’s something that will come up later. When you have a level of privilege, or power, of being in your own space, that’s what I’m trying to capture. It’s not for you, and not totally for me, it’s that level of wanting but not being a part of something. It is impersonal and still. Something has happened beyond my reach and I cannot affect that.

Do you remember those architectural images of rooms where I said, it looks like a human has never touched those surfaces before? It’s similar to that. It feels like humans design spaces for us. So when we have spaces that have never been touched by a human, what power does that have? It sheds some light on interesting aspects of the work. There’s a real sense of loneliness, stillness, floating. These are not bad things. But, it has something to do with being spaces from memory, not from photos. From absolutely creating them. They’re spaces that don’t literally exist but they’re familiar because we recognize them as what a space can be. I’ve been trying to keep the people (figures) out of the spaces. I’ve gotten to a place in the work where I, as a queer painter, question what kind of figures are in these spaces? You need to make it so everything is very intentional, everything speaks to a greater narrative of the work. I’ve been very careful, but now I’m starting to speak to these figures. Like [Late Visit]. Or [Alley Kitchen] has a small alley window with someone chopping chicken. They’re big, homunculus, [spaces] that have never been touched by humans, and now there are people in them.

AG: What I get from that is your work has always considered the absence of people. Even whenever you’re introducing figures.

PSJ: Yeah. The best way I can think of it is: if there's a person in the room, then the room is being used – it’s a product. I think making paintings of products is a little gauche and not where I want to go. At the moment, when I get a sense that the room is being used, it feels insincere to me. So, I try to speak around that [by] leaving a lit cigarette in a room, an open book, a door slightly ajar, a dog (Mies) walking out of the room; that feels better to me. It gives the spaces a sense of autonomy and agency. Through that agency is power. That’s really what I’m trying to work towards. Then, my larger goals, my 10-year goals, are how does that power benefit my community? How does it impact queerness? Me and those around me? How does that work speak about a queer artist?

AG: How do you feel about your first introduction of figures into your work?

PSJ: Well, I’ve omitted figures for so long that I didn’t understand the clothed figure. I was so used to painting nudes in undergrad, like, oh yeah, everyone’s naked. But I’m open to it and getting used to seeing it in my work. My goal is to paint larger, not just for the sake of painting larger, but I want to explore different supports and see what happens when these spaces become life-sized. I started working on paper. I feel the works on paper are so much more personal and I’m trying to decide why that is. I think it’s because there’s more nuance on the paper than on canvas. When I’m working on a painting it's very broad and general. I paint very fast – I can do it blindfolded. When I draw, making an image with the line, there’s so much more of myself going into it. I have to slow down and think about it.

AG: I was going to ask you if you feel differently about your works on paper versus paintings? I guess you’ve answered that. But I do agree, WOPs seem more intimate. Maybe they’re more organic or sentimental?

PSJ: It’s more personal for sure. I come from the elitist school of thought that WOPs are not as good as any different type of support. But I couldn’t disagree more with that sentiment. I think my WOPs are so much more personal and there’s more time and thought that goes into it. That is not the case with painting. There’s the school of thought that the WOP is just a multiple or a preparatory drawing. That notion is so damaging to artists, especially younger artists who may not have the resources to work that large, or work on supports at all. If you go into it thinking this is a WOP, it’s not going to be as good, that’s going to show. To leave that out of the work will change the attitude of what I’m doing. You’re doing it because you love doing it – you’re probably not turning a profit on little 5x7” drawings. It’s a detriment to paper, and just generally.

AG: It’s interesting. And WOPs usually deteriorate faster so they’re not as good of an “investment.” I hate that rhetoric but…

PSJ: But it’s there, so talk about it.

AG: Yeah, the obsession with having a painting that will last longer for your “long-term diversified portfolio of investments.” That’s part of what turns me off from the obsession with painting. Yes, the supports and the paint itself are more expensive, as opposed to pencil on paper, but still. But that’s part of why I like WOPs so much.

PSJ: How do I say this…I feel like I’m part of the problem and the solution at the same time. I think it’s important as an artist to think of it as “it’s just something that you do,” not something that’s less than something else. There’s a certain level of professionalism you should have with your work. But there’s that insecurity that when you’re buying a WOP you have to go through a lot more to make the artwork presentable: framing, matting, archival glass, sealed, and so on. And then the charm runs out relatively quick. But they are so charming. You can quickly fetishize paper. It’s so endearing. I worked with an artist a few years back who worked with paper as a casting material, and a lot of the physical work was at a paper mill. I’d help him pull paper. We’d do casts, it’s Dieu Donné, by Penn Station. It’s magical there. I think I have a different outlook on my relationship to paper because of this. No matter if an artist is working on supports, paper, or other media, there should be a reason and it should speak to the work itself. It’s important. There’s a level of intentionality that comes with that process, and it guides your work. It’s something I think about a lot, maybe too much. The biggest difference is that they do different things. If we see it as it’s not better, it’s different, but that difference has to come from artists, not collectors.

AG: Do you work on multiple pieces at once?

PSJ: Yes, I work on five or six at a time. I have these works on paper on this lovely Indian rag paper and because there’s this narrative of works on paper being more preliminary – that happen before or adjacent to the canvas – I think of how the precise story-driven objects exist on paper. Can they have their own personalities or lives outside of where they are on the canvas? In this blue work that’s drying there’s this window where you can see through the blinds someone walking, not really paying attention. There’s this figure coming out the door silhouetted by the light and there’s this table with a half-eaten tablescape of food. There’s this whole world outside the door that’s just out of focus. These are the objects. What are their personalities? How can they hold themselves within the piece?

AG: And most of your work is untitled.

PSJ: The way I see my titling process is: there’s that human element in naming something – a key identifier – that I really wanted to avoid early on. But you can’t not title something. It is both a missed opportunity and a detriment to the work. I cancel out everything I want to do in the work by naming it, but how am I ever going to identify it again without a name? So Untitled is the title, and the second portion is how you would describe the painting as if you were speaking of it in a sentence. Speaking about the painting without ‘naming’ it.

AG: That keeps it from being a “product,” as you’d mentioned earlier.

PSJ: Right. I don’t want to shoot myself in the foot by missing something like that. I used to always hate the untitled-parentheses-title but now it’s just a tool to get my point across.

AG: Are there any upcoming projects you can tell us about?

PSJ: I’m very excited to work on larger projects. Everything I’m doing right now I’m doing for myself. I have a few commission projects here and there that I’ve completed, some directional work where I’m offering assistance and creative direction, but I think when the world is maskless again I’m dying to show and be in a group setting. I feel it’s coming sooner rather than later. That may be the one downside of an art career during COVID: every time I talk to someone or have a studio visit it’s on Zoom. This time next year is going to be a very different situation. Let’s delay that question until next year, how about that? I’ve gotten really into framing, building my own frames. And thinking about what that does to the work.

AG: Goes back to you looking at every angle or facet of the piece.

PSJ: I built this frame. As you know, I’m a huge control freak and I want my voice and direction in every aspect. So, if I can’t go to a framer and have them do exactly what I want to do, then I’m just going to do it myself. I will mess up, but I’m not afraid of that happening.

AG: Also, artists’ frames are cool.

PSJ: It’s what comes attached with an artist’s frame, too, that “this is how the artist wants the work to be shown” and that’s considered part of the work. I don’t know if I’m saying that with my frames, that it’s holistically part of this piece. I’m experimenting. What kinds of frames will work with these pieces? WOPs gotta be framed. There's a lot of ways that a painting can look like a product and that’s important when framing works. How does this feel like an image, not “for sale.” I don’t want it to be commoditized if they are. It feels insincere and the humanist poetry is gone. It’s going to happen, should I be so lucky to be objectified, but I don’t want to go into it thinking of that.

AG: Ok, so I’m invited to your first opening when things open up?

PSJ: Yes, of course. I can’t wait to have an opening and have everyone there. I’m excited.

—

For more on Paul’s work, please visit his website or Instagram (@paulsebastianjapaz).

Anna Ghadar is currently a Candidate for the MSt in History of Art and Visual Culture at the University of Oxford.

Please follow us on Twitter and Instagram (@poltern_) for updates and share our newsletter with anyone who might be interested.