Our Mission:

Poltern is a platform for writers to confront contemporary issues in art history, edited by four current graduate students at the University of Oxford. Divided into four sections – features, reviews, creative writing, and interviews – our goal is to engage with current discourse in the discipline and provide a space where other early-career creators and writers can do the same. On Poltern you will find creative and critical writing by art historians, interviews with artists, and coverage of current events. Centered, but not moored, around our status as Oxford-based graduate students, it is our hope that Poltern develops with us as we continue our journeys beyond our current institution.

Its title is a German root meaning to crash or make a racket. It embodies what empowers, invigorates, and inspires us daily in our work in the arts: a concern for creating fissures and effecting change in the art institutions and structures from which our field has developed. We hope it inspires you, as well.

Art, alive, online | Short Reviews Series

By Sarah Jackman

Art, alive, online is a Poltern series which spotlights and reviews the spaces, people, and approaches which have kept the art world thrumming throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, despite its ‘unprecedented’ challenges. Featured below are three small reviews, summaries, and suggestions of online homespun projects that have shown resilience, innovation, and adaptation, keeping arts discourse afloat despite many restrictions. Each organization featured is a reminder to keep making new platforms, new spaces for new voices, and new ways of connecting through art during the pandemic and beyond.

Art thought - The Inbetween Collective

‘Learning together’, ‘creating space’ and ‘sharing ideas’ are the values at the heart of The Inbetween Collective. The growing platform is ‘dedicated to fostering critical thinking, community building, and nurturing our creative expression’. Led by two University of Leeds graduates, Megan Elliot, and Karma Abudagga, The Inbetween Collective is an open platform featuring conversations held over Zoom. Each free zoom session begins with an informal welcome by one of the two creators, avoiding and thawing the online clumsiness endemic to online conversations and fostering connections of the sort we’ve missed over the last year. This atmosphere and ethos of the calls open the space for sharing, listening, and connecting through writing sessions, idea workshops, conversations, and book clubs. During these sessions, conversations remain relaxed but expansive - from discussions of ‘radical love,’ ‘donut economics’ or Claire Denis’s Beau Travail. The collective’s sessions grow organically from one another, from a conversation about Beau Travail to a film screening introduced by a recent member of the collective. This is a sure sign that there are no implicit hierarchies in this collective; it is truly for all to contribute freely, fluidly shaping the collective together. Not only does the platform engage actively online, but the creators also have an Inbetween Collective podcast built upon conversations with new creative voices focused on creating inclusive spaces in the fringes; The Girlford Collective, for example, talk about their inclusive skate community, encouraging ‘everyBODY’, particularly minorities within and outside of the community, to skate. The Inbetween Collective platform aims to work together to ‘share ideas and inspire conversation,’ rejecting fixed binaries, and it achieves this with ease. The collective feels refreshingly inclusive, creating space for all opinions without judgement whilst still getting gritty with ideas.

Architecture - Folly newsletter

Started in 2019 by a young art and architectural history graduate from the Courtauld Institute of Art, Rosie Ellison-Balaam, Folly focuses on stories of ‘architecture of the past and present’. Published once a month, the newsletter does not chase stories but slowly presents architectural encounters, ideas and theories to the general reader. Texts vary from series of ‘Rambles’, following chance encounters with architectural structures during lockdown walks, to reviews of exhibitions such as Zoe Zenghelis at Betts Project. Folly 21, February's newsletter, focused on a theme familiar to most, looking to sheds. The letter asked individuals to submit their images of their own sheds to create a ‘shed gallery’ whilst also including personal responses to sheds and a review of James Castle’s Shed. Content is, therefore, thematic, or wide ranging, within every short newsletter. This is, in part, because the newsletter operates on an open call basis for anyone to contribute their works and architectural ponderings. Submissions collated from the 2019 – 2020 newsletters were compiled into a short, printed publication. All proceeds from the edition were donated to New Architectural Writers a ‘free programme for emerging design writers, developing the journalistic skill, editorial connections and critical voice of its participants.’ N.A.W. focuses on black and minority ethnic emerging writers who are under-represented across design journalism and curation. Folly is a gentle, monthly reminder to keep our eyes open, to consider and to capture the environments in which we live, and to share these encounters.

Podcast - Empire Lines

Empire Lines aims to uncover the ‘unexpected, often two-way, flows of Empire through art.’ Interdisciplinary thinkers use individual artefacts of imperial exchange, revealing the how and why of the monolith "Empire’’. Produced by Jelena Sofronijevic, as of October 2020, the series is adding new voices and ways of looking at the decolonial turn that sits at the forefront of much of arts and heritage thinking today. Through two 15-minute episodes a month the podcast covers vast and global content, through the lens of individual artistic endeavours. George Chinnery’s Self Portrait of the Artist in Macau (1844), two 10th century Islamic bronzes and John Bernard Shaw’s John Bull’s Other Island (1904) gives a little taste of the global and temporal ambitions of the series. Speakers range from new journalists such as Megan Kenyon, to researchers like Dr Glaire Anderson, all of whom approach empire not as an expression of uniform power but bi-directional cultural exchange. As Empire and the legacies of empire are, rightfully, being grappled with more and more in arts and culture, Empire Lines, demonstrates how the specificities of observing one object, artwork, play or book at a time can give real insight into the global and material impact of empire.

—

Sarah Jackman is currently a Candidate for the MSt in History of Art and Visual Culture at the University of Oxford. She can be reached at sarah.jackman@cc.ox.ac.uk

If there are projects you wish to write about, read about or have started yourself, reply to this email or submit to Poltern @poltern_. All the links to the projects are embedded in their names, check them out online. Next week’s newsletter will look to three more spaces, so subscribe to Poltern for more suggestions of things to follow and join.

The Right to Breathe

By Victoria Horrocks

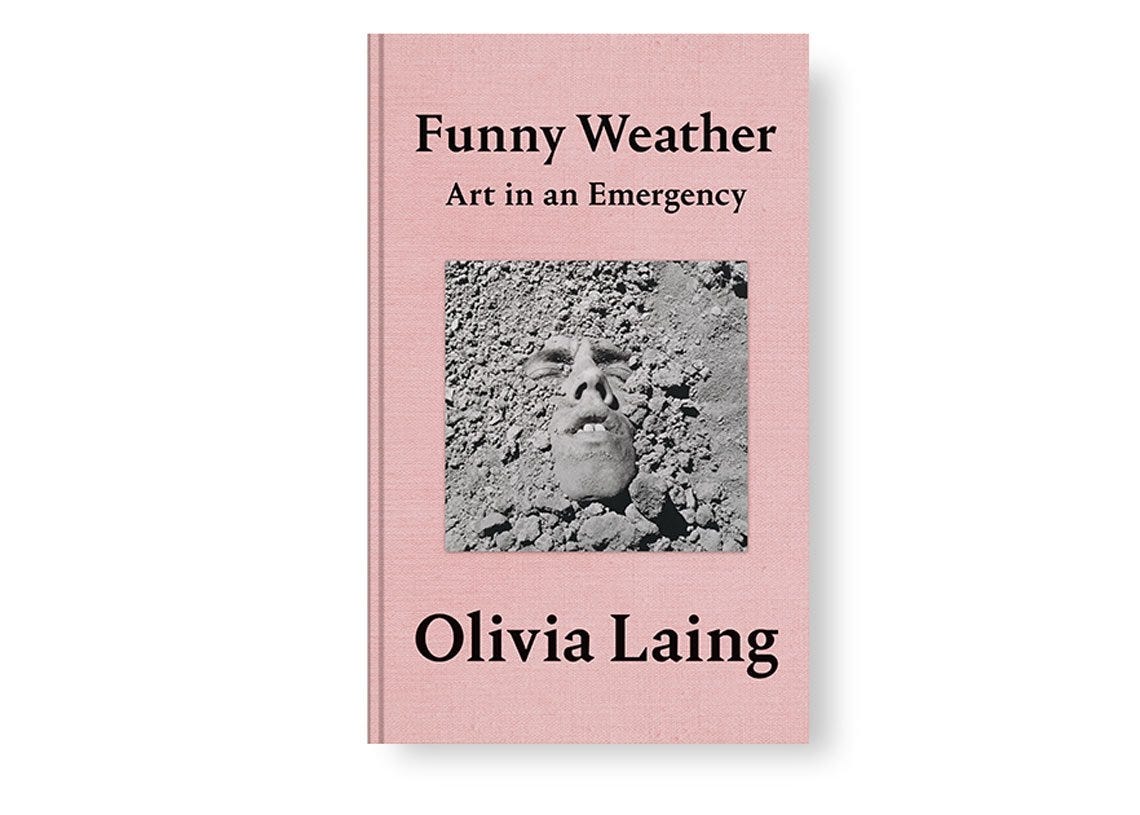

I spent much of summer 2020 staring at David Wojnarowicz’s Untitled (Face in Dirt). I stole morning glances with him from my bedside table, caught him—restrained—in a tote on the downtown 6 train, and inadvertently lathered him in residual SPF 30 at some point along the Atlantic coast. Untitled (Face in Dirt) was printed on the cover of Funny Weather: Art in an Emergency by Olivia Laing, which had been recommended to me by a friend in May, nearly three months into the Covid-19 pandemic.

It took me weeks to read the entirety of Funny Weather, a collection of compelling essays about why art matters. Nonetheless, Wojnarowicz covered little geographical ground. He moved mostly from bedroom to living room, although he made the occasional trip downtown for essential hospital visits or a socially distanced walk on the beach. For as much time as I spent with Funny Weather, though, I still wrestled with the peculiar image on its cover. Staring at Untitled (Face in Dirt), one questions whether he is rising, like Lazarus, or sinking into fractured earth. Is he animated, skin touching air, after death? Or is he in anguish, eyes sealed shut and accepting entrapment, forever at the whim of the pesky preposition “in”? His eyes are closed, but they are not clenched. His mouth is open, but he is not gasping. I wondered, is he breathing?

It felt fitting, then, that Untitled (Face in Dirt) would make the cover of Laing’s book at a time of such global emergency. Both artist and image are concerned with the right to breathe; both address life and death in a way that exhausts and reinvigorates all at once. Throughout his life, Wojnarowicz ardently questioned who was given the right to breathe as an activist during the AIDS epidemic, a time when his community was brutalised by disease. The government enacted violence in the form of neglect, and people were dying at the expense of that violence. Crude parallels could be drawn to the moment of May 2020, when governmental inaction led to mass death, and questions spurred, once again, about who was allowed the right to breathe.

It seemed to me, four months into the pandemic, that we stood at the threshold between action and inaction—compelled to repair, to heal, and to reinvent, all while confined to various iterations of the same four walls. Still, entangled, we navigated the thorny space of reckoning. Confronted with injustice, and unsure how to take action against it from a folding table-turned-desk in a childhood bedroom, I mined all that I consumed for wisdom and answers. Disease was spreading. People were dying. Breath was as vital as it always had been, but it had immediately become more precious and more privileged.

All the while, there Wojnarowicz was, staring at me with eyes closed. The image was taken in 1990 on a trip Southwest with photographer Marion Scemama. It would be his last trip out of New York. At the time, Wojnarowicz was in a state of emergency after receiving his own diagnosis of AIDS two years prior. Passing through Death Valley, he asked Scemama to take his portrait. He dug a hole in the ground, half-buried himself in earth, and the resulting portrait captures him lying in what appears to be a shallow grave.

Untitled (Face in Dirt) recalled, to me, one of three portraits by Wojnarowicz of his dear friend Peter Hujar moments after his death. Taken from Hujar’s hospital bed, the image captures a moment of extinguished breath. The 1987 portrait displays the face of Hujar, having died from AIDS, lying on his back, eyes slightly open, and mouth softly agape. Untitled (Face in Dirt) takes a similar angle. It focuses on facial expression, mapping life and death. Unlike Hujar, however, Wojnarowicz has his eyes closed, and his eruption from the earth breaks from some inertial state. His emergence from the grave is fraught with conviction. I sensed a resistance. Living with his diagnosis, but living nonetheless, Wojnarowicz made himself present. From the earth, he claims a breath.

In the very beginning of the pandemic, another friend of mine lent me her copy of Bluets by Maggie Nelson. At the time, I scribbled an excerpt in a notebook that read:

Perhaps it would help to be told that there was no bottom, save, as they say wherever and

whenever you stop digging. You have to stand there, spade in hand, cold whiskey sweat

beaded on your brow, eyes misshapen and wild, some sorry-ass grave digger grown bone-

tired of the trade. You have to stand there, in the dirty rut you dug, alone in the darkness,

in all its pulsing quiet, surrounded by a scandal of corpses.

I cannot say if this is how Wojnarowicz felt, since he died two years after Untitled (Face in Dirt) was taken. But I imagine he and Nelson get at something similar—that we each stand, shovels in hand, wondering how deep we must dig, only to realise there is no bottom. Then we are left with dirt on our hands and the exhaustion of the craft. Like Nelson’s image of standing at the grave, surrounded by atrocity and washed in fatigue, Wojnarowicz lies in his own eerie resting place. Still, he is not at rest; he reasserts himself in the world, invigorating the lungs and taking a gentle breath, as if to remind us that in presence, there is resistance. So long as we remain, standing in the grave, breathing, we can act.

Wojnarowicz was driven by such action. Assertions of life pervade the body of his work. Fittingly, the title of his retrospective at the Witney Museum of American Art in 2018 drew from the title of his work, History Keeps Me Awake at Night. As the pandemic pressed on, I began to read Untitled (Face in Dirt) as a call to awaken. Amid a resurgence of the Black Lives Matter movement, desperate pleas from government officials to wear face coverings, and many other calls to arms, all at once we were confronted with the dignity of breath. There I stood—as Nelson called it—in the dirty rut that I had dug, awakened to the inflation of my own lungs. I must pick up the shovel again and begin to dig.

—

Victoria Horrocks is currently a Candidate for the MSt in History of Art and Visual Culture at the University of Oxford. She can be reached at victoria.horrocks@hertford.ox.ac.uk.

Cotter, Holland. “He Spoke Out During the AIDS Crisis. See Why His Art Still Matters.” New York Times, July 12, 2018. Accessed March 2021. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/07/12/arts/design/david-wojnarowicz-review-whitney-museum.html

Donegan, Moira. “David Wojnarowicz’s Still-Burning Rage.” The New Yorker, August 2018. Accessed March, 2021. https://www.newyorker.com/culture/photo-booth/david-wojnarowiczs-still-burning-rage

Laing, Olivia. Funny Weather: Art in an Emergency (London: Picador, 2020).

Nelson, Maggie. Bluets (Seattle: Waves Books, 2009).

“Tales from Tiksi”

By Hannah Kressel

Siberia is a place defined by superlatives: the coldest, the farthest, and the most isolated, to name a few. Encompassing the most northern and western parts of Russia, the province is home to Russia’s arctic coast, making it worthy of such biting superlatives. However, it is also home to people and communities that once bustled, despite the glacial winter climate. One such community is Tiksi, a town located on the shore of the Laptev Sea in the Republic of Yakutia. It also happens to be the birthplace of photographer Evgenia Arbugaeva.

Arbugaeva was born in Tiksi in 1985. She remained there for the duration of her childhood. However, when the Soviet Union fell, the town was no longer receiving financial support and fell into neglect. Tiksi became subject to a mass exodus. Included in that exodus was eight year old Arbugaeva. She relocated to the Siberian city of Yakutsk and later went on to live in Moscow before moving to New York. However, she never forgot her beloved childhood home of Tiksi.

In 2009, Arbugaeva decided to return to Tiksi, drawn by dazzling memories from her childhood of epic horizons and fierce winds that could nearly lift a person into the air. In her photographs, Arbugaeva threads a luminous narrative through the jutting frozen landscape and ferocious winds of Russia’s arctic coast. Tiksi becomes the setting of a blithe tale, following a young girl named Tanya. Arbugaeva met Tanya when she first returned to Tiksi in 2009. Arbugaeva writes, “Tanya and her mother were sitting by a fire at the seashore, looking very sad. So I started up a conversation. They told me that Tanya’s older brother and sister had left that same day to go to college in the big city. I shared my own story with them.” Tanya would become the subject of many of Arbugaeva’s photographs shot throughout Tiksi.

One image features Tanya dressed in insulated overalls and grey boots with a knitted red hat on her head. She stands in a room; behind her is a tapestry painted with a seascape image. Golden and maroon reflections of the sun stripe the rocks, the color of which is mimicked in stripes on Tanya’s overalls. To the left of the image is a fridge, and to the right is a potted plant and a lacy curtain. Despite the fact that she is indoors, she holds a small telescope to one eye. The image nearly feels like a scene from a Wes Anderson film. Arbugaeva captures the eccentricity of youth — the ability to craft tales — expertly. Although the image behind Tanya is painted and the usefulness of a telescope within her home is farfetched, Arbugaeva accesses a universal nostalgia for the wonder of childhood. Another image shows Tanya, this time wearing red rain boots and a blue dress with white trim, balanced atop a piece of ice. Her two braids, fastened with teal tulle, are swept to the side by the wind. She leans over, a hand stretched out to a dog who stands in the water that surrounds the ice upon which Tanya balances. Save for her red boots, the scene is a wash of blues and grays. There is something enchanting about the image. Arbugaeva offers a Brothers Grimm-style archetype: that of an orphan child, encountering a robust world.

Evgenia Arbugaeva truly teases a tale from the vibrant memories and remains of her childhood in Tiksi. In an interview, she explains that, sometimes, she “[returns] to [a place] over and over again — at different times of the day, in different seasons, with different moods, and with the tremulous hope that, at some point, it will open up to me.” Although the Arctic is not the quintessential location of fairy tales, Arbugaeva fashions one: a melding of documentation and the magic of her reminiscence. In an article written for the Guardian, she explains, “I think the experience of taking this image was a closure for me. Through Tanya, I was able to reconnect with my childhood, to make sense of the place I had left and to rediscover the Arctic as my homeland.”

—

Hannah Kressel is currently a Candidate for the MSt in History of Art and Visual Culture at the University of Oxford. She can be reached at hannah.kressel@wolfson.ox.ac.uk.

Artist Interview with M Woods | 15 December 2020

by Anna Ghadar

I spoke with Michael Woods – a mixed media artist currently based in Oxford – about growing up in the NYC-area, his mentorship by the late Aldo Tambellini, anti-racist activism, time-space, and, of course, his extensive artistic practice. Woods, who shows under the name M. Woods, is currently an MFA Candidate at the Ruskin School of Fine Art, University of Oxford. From his website:

M. Woods (born 1988, NYC) is a Latino media terrorist working in avant-garde film, video art, photography, collage, sound design, performance, curation, installation, music composition, and immersive media. He is a member of Kiira Benzing’s Double Eye Studios, a board member at The Vast Lab in Los Angeles, a represented artist and guest curator at the Los Angeles Center for Digital Art, and a co-founder of the avant-garde international union Agitate: 21C. His short film work is distributed by Collectif Jeune Cinema, Paris. He has shown over forty short films at festivals and galleries internationally, including three feature films, work in VR, performance, and still photography, and he is working on the completion of a large body of work which is an interactive exhibit and transmedia experience, The Numb Spiral. His work has been shown at the Rotterdam International Film Festival, Venice Biennale, Tribeca Film Festival, the Oberhausen International Short Film Festival, the Hamburg International Short Film Festival, Artists’ Television Access Gallery, Experimental Response Cinema, and Fracto Berlin. He has had masterclasses/retrospectives at Lausanne Underground Film Festival, Cámara Lúcida & the Cuenca Museum of Contemporary Art, Videodrome 2, and L’Hybrid. He has won awards at Festival Tout Courts Aix en Provence, Hazeleyes Film Festival, and Montreal Underground Film Festival where he won the top prize in 2017.[1]

We began light – as light as a conversation can be in 2020 – chatting about being American in the UK and the complications that come with ‘celebrating’ the holidays during a pandemic.

Michael Woods: I’m glad I’m over here [in England] this holiday.

Anna Ghadar: So, you’re from New York, were you born and raised there?

MW: Well, it’s a little complicated. I was born in NYC but lived with my grandparents in Long Island - in Huntington. My grandmother came from Costa Rica – my mother is from Costa Rica – and they came over in the early 60s. My grandma, and my grandfather, had worked really hard to get a house in Long Island. My mother’s marriage to my biological father broke down right around the time I was born so I didn’t really have him in my life. Quickly after I was born, we went to live with my grandmother until I was nine. Then we moved to Chicago. Just North of Chicago – Evanston. Everyone from Evanston always says Chicago because it’s easier but it’s where Northwestern University is. Long Island is still in my accent a bit.

AG: Well, I don’t hear it but maybe some words will stick out. I don’t know what ‘Long Island words’ are specifically.

MW: There’s these phrases where you can make out all the Long-Island-isms. We have very long vowels when we speak.

AG: When was the last time you were home? Because you moved from Boston or Cambridge [Massachusetts] just before coming to Oxford.

MW: Yeah well, in 2018 I was working in Los Angeles – and I have a daughter too.

AG: How sweet! How old is she?

MW: She’s five. Annmarie is actually my impetus for coming to this program and for a lot of the hard work I’ve done in the past five years. Really kicking my ass. Unfortunately, my marriage to her mother ended, and I had been with her mother since I was in high school. [After the separation] her mother moved to Texas quickly with Annmarie. I lost my job in 2019 and I drove across the country and I actually lost my apartment. So, I stayed at friends’ places, Airbnbs, sometimes in the car or with family. [I] showed my movies and it helped to get me [to Ecuador]… then, in 2020, I went to Ecuador for three months to be with my grandparents. When I came back – in between hopping over to my grandparents – I went to stay with Aldo Tambellini.[2] Aldo has a loft in Salem, Massachusetts. That’s where my partner and I lived. Aldo has, or had, an apartment in Cambridge so [my partner and I] would come over and we ended up being the people who did all the errands because Aldo was 90 when he passed away. That’s why I was in Cambridge. [I] was there for what should’ve been a month and ended up being seven or eight months.

AG: That’s great though, to start growing roots in a place.

MW: Absolutely.

AG: How did you and Aldo meet?

MW: I met Aldo in 2013 [through] one of my best friends, Michelle Chu - who’s actually in the Art History program at Columbia University right now. She called me Woody because that’s the old nickname from back in the day. We went to NYU film together.

AG: I actually have your CV pulled up here. So… class of 2010, right? With honors!

MW: Yeah, there you go. I was like, should I be back to get a doc?

MW: So, Michelle is much smarter about the overall body of work of avant-garde and experimental film. She’s like, how do you not know Aldo Tambellini’s work? And at that point I hadn’t yet seen anything [by Aldo]. Then I saw Black TV at a point that was really dark in my life.[3] After seeing Black TV, it was a wakeup. There was something really communicative about what he was doing. It didn’t avoid the political, which was a lot of the avant-garde, especially at that time, just avoiding the political. Aldo full on saw that the experiments in phenomenology, experiments in the cosmic, and action of civil rights or advocacy. He was part of the Black liberation movement, so he was real radical. They were all part of the same thing. There’s a level of purity in the avant-garde film and experimental film world and Aldo eschewed that. And when it’s a video and it’s a virtual reality. Towards the end of his life, we talked a lot about VR, and he was working with a South Korean artist – [Dae Gyeom Heo, whose American name is] Blake – [and] they were doing computer generated VR for Aldo. I documented [Aldo] a lot. We were working on a short film together right before his death. I told him there was a certain level of sensitivity to the subject of Blackness that is, especially right now, important to keep sacred. In working on it [the unreleased VR project] Aldo wanted to make a piece that was radical, but it was radical in the way that it depicted violence against Black people [while] meaning to do the opposite. And it was found footage for this [project]… it’s kind of extraordinary. I spoke to him and I said I don’t think this should be put together, and he agreed with me.

AG: Broadcasting Black suffering versus exposing it.

MW: That’s exactly right. Aldo, of course, had done a lot of the work during his life. He was definitely an accomplice, but he also showed wisdom even at the end of his life. He needed to talk through his work. Through him I saw a sort of example.

AG: That’s amazing. It sounds like you had a really rich time with him, which is great.

MW: I did. He was like my grandpa. It’s sad, I went through a two-week period where any time I started to talk about him I would just cry. Now I feel like I see him. It’s weird, after he passed, I started getting these perception shifts in my practice and in the way I was looking at time-space. He, of course, was looking at a lot of that in his work. Even experiential space, virtual space, the way that we engage in virtual space – the trancelike effect of cinema versus virtual reality versus accessing a soft, cool media of, like, the internet. There was a big shift of mine after he had passed away that came with [Aldo’s death]; [a shift] that allowed me to reevaluate what was going on. I also think of him as not in this point in time and space, but he is at a different point in time-space where he is visible and so there’s weird clarity to it now. You know?

AG: And what do you think are the biggest impacts that experience of the grieving process had on your work now?

MW: Right now, it seems stupid, one thing that happened at Aldo’s funeral…the priest started talking about how the artist sees things inside out. It’s one of those things that when you hear from someone who’s not even very well versed in art it might sound amateurish, as if that’s a bad thing, but instead there was something that’s very true about it. And there’s something about the inside out, the upside down, the flipping of things. I thought about two things: the idea that we might possibly live in a slipped dimension, in which 10- or 12-dimensional space is not available to us, but there is a 4-dimensional space. So, the idea is there’s a slip. That’s kind of what David Bohm is talking about in the implicate and explicate order of time-space.[4] So I began to think about it, because my work is centered around a weird phenomenon that’s hard to describe: it’s called the numb spiral, in which somebody negates reality through their own perception, through their own philosophical framework – let’s say – so that they either receive or self-generate. So, I began to think that the solipsist, the person who’s in the space of mind to only perceive themselves and sees everything as an extension of themselves - as arising from themselves - would then, as a result, see the world as a sort of completely flipped inside out in some way. It wasn’t that they necessarily perceptually see the world in that way, but it’s that the solipsist almost has a sense of themselves as the ring around the world. I’ve been looking at the books of Jew of the gnostic bible and they have a conception of the eighth terrestrial sphere as the serpent or dragon eating its tail.

AG: The ouroboros? Is that it?

MW: Yeah, and the thing is the way it appears is in a map in which they also made…Roman gods the evil layers of the terrestrial sphere. They also have Jupiter, Saturn, and so the interesting idea that came of it, sort of tangential, was the idea that that sort of subs for it. The solipsist is sort of eating itself, and it is a ring around everything. So it’s cosmic view is flipped or folded inside out. It has another slipped dimension – that’s the dimension of nothingness. That’s sort of the slipped dimension of the way in which they are positing themselves as being everything, which in a way makes everything nothing. I’m interested now more and more in this folding and this negative. Like, the idea of the negative and the positive have become really huge as they pertain back to even just the silk-screening process, but also the film process, obviously. And thinking of the way in which the ergonomic design of organic beings fits this sort of environment. In a way, we become positives and negatives of each other. And that all just kind of came at my thinking after Aldo had passed. And so, I’m starting to work these things in but trying not to actually plan out my interventions with the media I’m planning out. I’m also making a narrative movie right now.

AG: That is so cool. As the MFA project or dissertation?

MW: Yeah, it’s a dissertation and it’s also a digital presentation.

AG: It’s so interesting to hear more about your practice, because of course I’ve seen your work and I’ve lurked around on your website but to hear the process behind it and the work that isn’t get displayed online is so cool.

MW: Yeah, that’s the tough part. The stupid ways the film festivals work I can’t put some [projects] up that I wish I could, you know? Sooner rather than later. I put most of my movies up, but the feature films are tough because in order to even get them played… it’s a little bit tough. For me, that’s a huge honor and privilege, thank you for even looking at the stuff.

AG: Of course! How did you find the Ruskin school? Of course, everybody knows Oxford, but coming from the US, coming from New York, how did you decide on the Ruskin MFA as opposed to anywhere else? Or potentially staying the States?

MW: I’ll be honest with you… I think I’m probably going to have to go back to the States because the truth is, I don’t want to be very far from my daughter and she’s already very far from me and it’s really difficult. But the other thing is I looked at the available MFAs that I thought would speak to, first, a mixed media practice that wasn’t locked down to a specific media, because that wouldn’t work at all for me. Then I also looked [to be sure] that there were some faculty that were better than me at any particular media of my choosing. I wanted to see where I could expand. I also saw how short [the Ruskin MFA] was – in 9 months I could get a master’s degree and be back in the United States so I could actually make some money teaching because without getting a teaching gig…. I was working as a teacher part time while I was working in Hollywood, essentially, while I was doing some technical crap. It never paid the bills, it’s ridiculous. I knew that I had to take the opportunity [to join an MFA program] while I had it. I’m also super privileged to have my mother – my mother worked from being completely poor as a kid to being an architect, and she was the first of our family to go to college. She got to a point where she provided [for our family] and she’s helping me out with this opportunity. So, if it wasn’t for my mom, I wouldn’t have anything. She’s tough. She’s a tough mom, you know, she’ll give everything, but she’ll scream while she’s giving it.

AG: Of course, my dad’s a little bit that way. He’ll say, “you can do whatever you want, and I will support you, but you have to be the best at it” and I’ll be like “alright!”

*both laughing*

MW: You know, you know! That’s the way it is. But also, my mom doesn’t get anything of what I do. She doesn’t necessarily like it. She likes my photos, but she doesn’t like the movies.

AG: Do you think her architectural practice has impacted your work at all?

MW: I think so… Recently I’ve been making these ugly looking blueprints; I’ll show you one.

AG: Yeah, show me.

MW: This one’s something I call maggot house…

*Woods holds up blueprint sketch to the camera*

AG: It looks sort of like a cell or an amoeba.

MW: It’s called the maggot house. If it’s drawn to scale it’s really huge. There’s something written on here that is interesting: the cyclotron. Here, it’s a little bit difficult because I bet it’s flipped for you. Aldo was messing with this idea at the end of his life that you can create an, essentially a room, he didn’t put it in these terms, but it operates sort of like a cyclotron, which is a way of speeding up particles. Now, Aldo and I were also obsessed with the spiral, that’s part of the reason we really got on as artists. So, the spiral is a sphero-magnetic spiral that then speeds up the particles and they go into a helical motion. This is also something that I’m becoming obsessed with – or have been obsessed with in my work – is spiral staircases. But the cyclotron is also an experience that Aldo was theorizing: that you could create a space that had so many different mediated experiences that it’s like you have an over-saturated space, but that it kind of creates a subliminal space, an occluded space, or an experience that’s hard to describe without saying that it’s a subliminal experience. He was achieving that through things he was doing in New York, through the Black Gate, an amazing performance space he created with live poetry, performance, short wave broadcasts [and] Lumagrams – these projected stills and slides. I began to think actually that, yeah, you could build an entire exhibit and – this is where the segue is to architecture – I’m looking at how it can fuck with blueprints for the Guggenheim and other spaces. To create a theoretical physical exhibit. So, this is a house that I would supposedly build for a movie, and the movie won’t be released for a long time – if it ever does get released. I started to think about my mother’s practice because I’ve always rejected it. You know, I hate architecture and the way that they consume it. It’s the flipping that’s occurring here in the experience [of the maggot house] there’s a way in which you… turn it on its head.

AG: So, when I think of the process of flipping, I also think a lot of making the invisible visible and exposing processes. Does that play a part in your work, you think?

MW: Yeah, definitely. I think there’s one thing that’s always at the heart of my work: that there’s a sort of underlying issue that I have myself with my own identity. It doesn’t play out really that blatantly in any of my work but that’s also part of the way I express it. It’s also hard to speak about my work because I have a body of work that I’ve been working on for a long time and then I have the work that’s been shown to other people. But part of my work is a narrative movie, that in some way has a reflective doppelgänger of myself. And that’s a sort of white version: Wes Pierce.[5] I think that in some ways that is a process that I look to unfold in my work: the way in which whiteness operates in a space and generates nothingness and the way it generates Nihilism.

I would say that my work also talks about an architecture of Nihilism itself, an architecture of nothingness itself. Not in a tangible way that is sometimes missed when people discuss existential nothingness, but the void as it were between us and other things or between us and however we perceive ourselves different than “the other.” That architecture is inherent in the process towards losing reality. It’s also inherent in the process of indoctrination and philosophical brainwashing. Which, all of those things combined, kind of create the kind of larger decay, the larger problems of the world, the larger oppression of the world. So, in many ways I think that my work tries to elucidate these structures in some way while at the same time even pointing out that this is it. And that the nothingness behind it is actually – and this may be the controversial aspect of my work – that looks to express that nothingness is conspiratorial. It actually has a sort of spirit to it that is negative and there is an aspect of it that this is part of all human reality. That in this concoction of nothingness that we need to make in order to have everything that we’ve actually created something that can be an evil in that sense. And I know it sounds religious sometimes, but I do think that this is at the heart of my work: a fear of that evil that is produced.

AG: I’m thinking that the fear – that anxiety – that is at the core of a lot of religions is really interesting... But I’m also thinking that when you talked about whiteness as the void it reminded me of Richard Dyer’s White – I don’t know if you’ve read that. I should send it to you. We had to read it for the MSt [in the History of Art] class and [in it] Dyer talks about how whiteness, and racial whiteness, is created as the baseline or devoid of color, or ‘the standard,’ and in turn Blackness is [posited as] the opposite of whiteness. All of the things that whiteness is, like purity… whatever whiteness connotes in film, or in anything really, Blackness is then the opposite and this has created a[n artificial] racial hierarchy in film along with most other art. Dyer also talks about interesting things that go with negatives – like photographic negatives – and how you can invert negatives because of the black and white binary in film. I’ll send it to you, now I’m just rambling. But it is interesting and reminds me of your work.

MW: That actually reminds me of Aldo’s work, too. There’s a movie called Black Plus X that got around the idea that the Kodak film stock was being produced in such a way that favored lighter skin tones because of the latitude of the film and the proper light meter reading for it.[6] What Aldo was doing is that he began to flip it into a negative in order to represent his friends in a way in which they were actually having fun, too. His work was looking at them in Coney Island and their children were out playing on one of the Coney Island rides, and he employs multiple exposure and flipping and cross processing the footage – so selectively cross-processing the footage and doing multiple exposure. But I think that’s part of the reason he switched off of even using film to video. He saw some of the limitations of [film] as a media. He inevitably used film mostly to film people out of his window or to film television sets – to film what was there already. But the piece is really beautiful, it also deals with this grappling of the way in which you can photograph Blackness. And what it means in relation to whiteness. Because that’s the other issue: the narrative hole that people fall into, this sort of diversity of visibility but never a diversity of stature within the narrative role or the narrative character is just so toxic in the United States, and also everywhere else.

AG: But in particular in the States.

MW: Well, also in the Latin American culture. Oh my god. There were minstrel characters being used on restaurants as late as 2018 in Ecuador. Images of just straight up little Black Sambo essentially. It shows how much [in] our countries – Ecuador and Costa Rica in particular – there is a lot of work to be done just in terms of inherent hatred of Blackness. It’s also an inherent hatred of the Indigenous and the two really go hand in hand in those countries.

AG: Like Social Darwinism and colorism meeting.

MW: Absolutely. My grandmother is just about 10% African because where she comes from in Costa Rica was a slave port. So, the likely conclusion, because we will never know, is that her ancestors in Puerto Limón – or a few of them at least – had come over between the 1780s and 1840s from parts of Africa that are known to be used [for trafficking enslaved people] by the Spanish. And you think about that and she’s also a quarter Indigenous going back 2,500 years and yet those are things she should be proud of. This is this ancestry she should love and even my own Grandmother has expressed thinking of herself as only white or her family as only white. Although the codification of people into genetics is problematic on one end, it is also necessary to shed another sort of invisible architecture there that she needed to know because it actually changed a good amount in her thinking. Sorry to go off on a tangent, but I think when you were talking about the processes or invisible structures – as we’ve been talking about very much in our cohort, but everywhere – is the effects of colonialism and the triangular slave trade.

AG: I was wondering – perfect segue – you said last week when we were [scheduling this meeting] that throughout the course of the term you and your cohort were working on anti-racist work in the Ruskin. I was wondering what that looks like and how your cohort approached that.

MW: I’ll be 100% with you: The Ruskin has a lot of learning to do on how it’s going to handle issues of anti-racism. Even the issue of anti-racism. For me, I came at the end of September but previously I had been at Black Lives Matter protests in Boston and Chicago. I had anticipated there would be a lull in physical activity out here, but I still was looking around. So it wasn’t that I looked into the Ruskin. Then, I had a meeting at the Ruskin, and the issue was raised that the Ruskin did not have enough diversity in its staff hiring, [in its] students, all around. Looking around that pretty much seems [to be] the case… I think [The Ruskin] has put a lot towards trying to address the issue of anti-racism [and is] starting to listen to people directly.

We had ‘listening sessions’ [which were] basically the students of color in the group [spoke] to fill in awkward silences about their experience while there were other white students who were saying: oh, that isn’t my experience, is that really your experience? and things like that… This added pressure to [the administration] and the added pressure of the white students in the cohort who were acting out of white privilege. You know, the way white privilege works is that they can be a perfectly fine person – you want to have a drink with them or a coffee with them – and you probably uncover that there is a lot that they need to learn. That probably added a lot of pressure, enough to make the students of color not want to participate... And then the results from the listening sessions were not necessarily productive. You know, they did not address the major issues that were raised. In the last 2 weeks I’ve been working with two other folks who are the [representatives] from our cohort, and [representatives] from all around the [university]. We expressed interest and said we want to be involved and they quickly created these groups… [and] I think that because of the direct feedback we’ve given to the administration we’ve [had a positive impact].

That means it’s a lot of ideating, a lot trying to figure out where everyone else is [emotionally], having conversations with many different people from several cohorts. We have representatives from all cohorts working with likeminded accomplices in administration and visiting tutor cohort. We’re trying to create a radical active framework that involves community outreach – bringing in outside groups to be able to directly benefit from the Ruskin as opposed to say, we want you to come and do a workshop, [rather], we want you to come [to Oxford to] do a workshop but also see if we can get you rental space of the facilities to use the Ruskin as a resource, as there are many resources here. Whether or not it’s pragmatic, we’re just going to develop what we think is a reasonable framework for the next five years and what we think [the university] need to do…

AG: That’s so true. And in the same vein – just coming from the History of Art MSt instead [of the Ruskin MFA] – a big question we’ve been asking from the beginning of the term is can we fix art history? Is art history raced, and if so, how do we approach it? How do we decolonize the canon, is that even possible, or how do we decolonize art history? We’ve been grappling with these questions all term and we will never find one set answer, obviously, but it’s a good thing to bring up and talk about… So, I’m wondering, how do your tutors or how does the MFA program approach that? Because we do it more with introducing art historians who have different positionalities, who are people of color, who are working on artists of color, and are doing more critical race theory in their studies or their work and I’m wondering what that’s like in the MFA program. If you’re bringing in more [post-colonial and/or critical race] theory or what?

MW: I think we need to change our pedagogical approach in general. The BFA go through Art History and the way they’ve described it to us is that they have a Black History Month for Art History. So, the idea of having a block in which they deal with Blackness would be problematic. That being said, the way it’s being dealt with in the MFA is that they provided us with a summer reading list that had a lot of great stuff on it. Then, when school started, the folks who bring it up and want to discuss this bring it up in seminars but otherwise it is not a thematic or driving force of any [substantial change].

Then, as if a reminder that nothing leaves 2020 unscathed, our video call cuts out along with the audio recording. Woods and I reconnect and pick back up the conversation for another 20 minutes or so. We continue to chat about how to incite change through art and academia. Woods then goes on to note issues with his health, including heart problems that consist of a vascular tube wrapping around his heart – which arguably contributes to his fascination with spirals, helixes and similar structures. I asked what had changed most in his work between his BA and his MFA – how had his practice changed in the past decade? He immediately noted that he had become more skilled with handling 16mm film – that he has become well versed in this particular media. Woods’ practice over this period has emphasized the honing of skill and refining of theories.

Woods then discusses struggling with drug addiction in his early teens – a period in which he abused alcohol, pills, and cough syrup. He notes the perception altering effects of these substances. Woods remarks that these drug-induced perception alterations have had a notable influence on his work, and that a “good dose of truth” is like a “good bad trip.” As if to say, good art exposes these aforementioned invisible structures and evokes pivotal realizations. Similarly, even with “bad trips,” one learns something indispensable. In this way, one can still extrapolate something meaningful or good from said bad trip. Woods then concludes that a good work of art makes you feel like you are a child again – it speaks to your inner child, so to speak.

We talked through the drug-like fixation we have with mediated representations of the self. This is an area of intrigue for Woods, who dubs this the digital sickness – a concept at the crux of the artist’s body of work. Woods notes that the digital sickness is an evil that leads the self “towards the eradication of the real and the propagation of its double.” Notably, his artistic process hinges on both sense of self and ideas of reality.

We close off the conversation with a final question:

AG: If you could describe the digital sickness in one word what would it be?

MW: Tentacular.

—

Anna Ghadar is currently a Candidate for the MSt in History of Art and Visual Culture at the University of Oxford. She can be reached at anna.ghadar@lmh.ox.ac.uk.

[1] M. WOODS, “DISASSOCIATIVE PRODUCTIONS,” the digital sickness. March 11, 2020. http://www.thedigitalsickness.com/. [2] Aldo Tambellini (1930-2020) was an Italian-American mixed-media artist renowned for his work across media including sculpture, poetry, film, painting, and most notably, video art. He is regarded as a pioneer in avant-garde and experimental filmmaking. He passed away at the age of 90 in November, 2020, in Cambridge, MA. [3] Aldo Tambellini, The Black TV Project, (1969-2019),multimedia installation, 16 mm film, black & white, sound, 14 min. Aldo Tambellini Art Foundation, 2019. [4] David Bohm (1919-2017) was an American scientist known most notably for his contributions to the fields of theoretical physics and philosophy of the mind. Here, Woods references his text Wholeness and the Implicate Order: Bohm, David. Wholeness and the Implicate Order. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1983. [5] Note from the artist: “(this is in the movie Melencolia - one of my upcoming feature films - and in my as of yet untitled Novel (tentatively just the Numb Spiral) - Wes Pierce is his name. My birth name was Pierce - my biological father's last name - and my mother wanted to name me Wes but chose Michael to keep my Father in the picture, but he left anyway.” [6] Aldo Tambellini, Black Plus X, 1966. 16 mm film, black & white, sound, 8:56 min. https://tambellini.no-art.info/films/1966_black-plus-x.html.